Safer journeys: giving each surgical patient the best prospects

Getting good outcomes from major surgery doesn’t just depend on what happens during the operation. The whole journey counts – from the decision to operate, through preparation for surgery, the operation itself, and the care we receive afterwards. Simon Howell outlines how ‘perioperative care’ could be the next big revolution in surgical medicine.

In the past, studies of surgery have often focused on survival in the first 30 days after the operation, what’s known as ‘perioperative mortality’.

But our immediate survival is only one of many outcomes that matter to us as patients! We hope for – and expect – to survive beyond one lunar orbit (to paraphrase a seminal article) and look forward to enjoying an acceptable quality of life after surgery.

If you’re healthy and undergoing a relatively minor operation, like a hernia repair, most of the time this is what you can expect. But this is not the case for major surgery and for those with co-existing conditions, such as respiratory or heart disease.

Even in the best hands, the risk of at least one problem after major abdominal surgery is over 30%. The risk of a life-changing complication is smaller, but important.

And there’s now clear evidence that post-operative complications have an impact months – even years – later. If you have a significant complication after surgery, you’re more likely to experience other medical problems in the years that follow.

Effective perioperative care doesn’t just depend on skilled clinical input. Patients need a coordinated ‘pathway’ of care that crosses through many disciplines and specialties.

Getting the best care for patients before, during and after their surgery is at the heart of my research.

I’m part of the Yorkshire Cancer Research Bowel Cancer Improvement Programme (YCRBCIP), which aims to improve survival for people in Yorkshire and Humber who have colorectal cancer.

Funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research, BCIP’s work spans diagnosis, drug and radiotherapy treatments, surgery, and what we now call perioperative care.

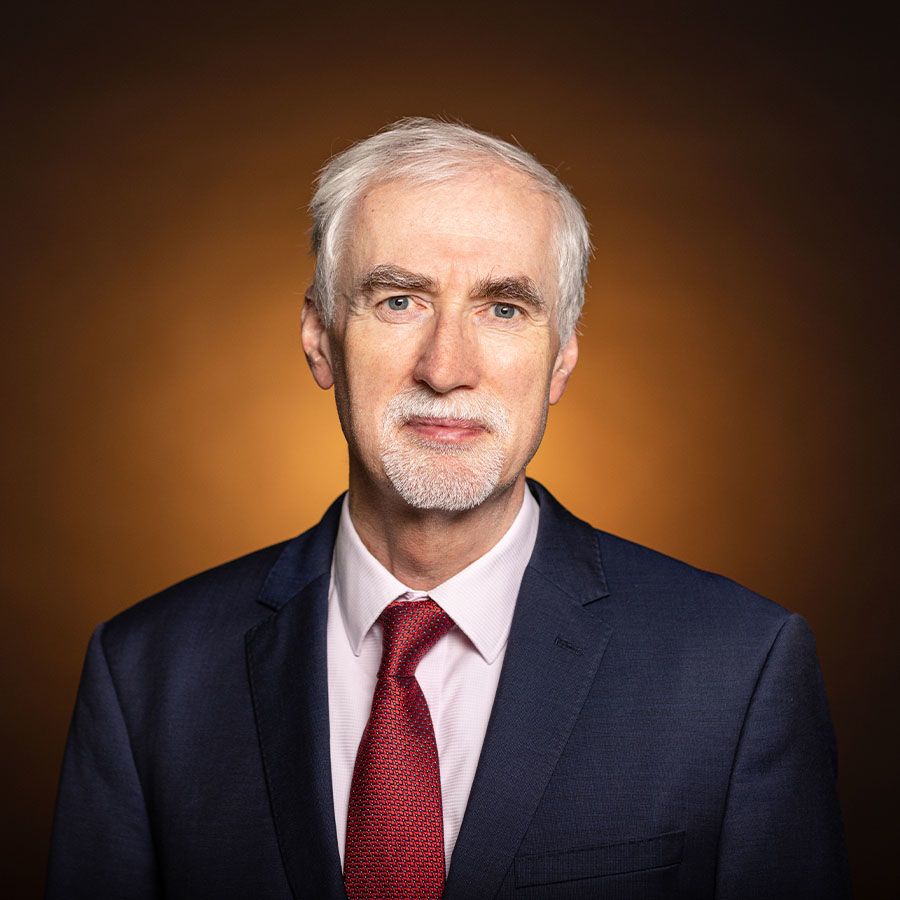

Simon Howell presenting an overview of the YCRBCIP and progress to date at the YCRBCIP Anaesthetics Education Event in 2019.

Simon Howell presenting an overview of the YCRBCIP and progress to date at the YCRBCIP Anaesthetics Education Event in 2019.

Anaesthesia is at the heart of perioperative care

I’ve come to this project after a long career in anaesthesia. As well as leading this BCIP work, I’m an Associate Professor of Anaesthesia in the Leeds Institute of Medical Research.

The anaesthetist has become central to patients’ care during surgery. In fact, anaesthesia was the first step toward modern perioperative care.

On 16 October 1846, William Morton demonstrated ether anaesthesia for the first time, in the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Surgeon John Collins Warren removed a tumour from the neck of the anaesthetised Edward Abbott. That operating theatre became known as the Ether Dome.

The use of ether spread around the world with remarkable speed at a time when international communication depended on eyewitness accounts and the written word.

The first ether anaesthetic in the UK took place at University College Hospital London on 21 December 1846. In March 1847, ether was used for the first time in India in Kolkata (then known as Calcutta).

The conquest of pain during surgery is one of the great landmarks in the development of medicine. Removing the agony of ‘awake surgery’ enabled complex and precise operations, often lasting many hours.

Treatments for cancer and many other conditions that had been beyond the reach of the surgeon’s knife became possible.

“The essence of perioperative care is meeting the needs of each patient”

Modern anaesthesia encompasses effective local or general anaesthesia and the wider oversight of the patient during surgery.

The motto of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland is “In Somno Securitas – safe in sleep.”

It’s the anaesthetist who ensures that the patient remains physiologically stable and that their heart, lungs, kidneys and other organ systems continue to function as they should.

They give fluid and blood and blood products, if needed, and also make sure patients have adequate pain relief during and after surgery.

But the past two decades have seen a further revolution in anaesthesia, with the development of perioperative medicine as a specialty.

What is perioperative medicine?

The essence of perioperative care is meeting the needs of each individual patient. Different patients have different problems, which must be managed appropriately.

Such care rests upon evidence-based protocols and guidelines, but the model is that of medicine tailored to the individual. It’s not a ‘one size fits all’ solution.

Perioperative medicine has three main phases: ensuring that patients are as fit as possible for any operation, that they undergo the best care during surgery, and that care after surgery stops major medical complications arising. Heart attacks, chest infections and kidney problems are all possibilities.

Supporting the patient to be as physically fit as possible before surgery reduces the risks of surgery and speeds recovery. Making sure that any existing medical problems, such as heart disease and diabetes, are effectively treated is an important part of this.

Bringing all this together has become the role of the perioperative physician. That physician is frequently (although not always) an anaesthetist.

What does the ideal surgical journey look like?

Soon after the decision to perform an operation has been made, the patient will receive a review in the anaesthetic pre-assessment clinic.

This will look at the best way to manage any existing conditions, such as heart disease, respiratory disease or diabetes. It will assess the patient’s physical capacity, for example through tests on an exercise bike or treadmill.

Where appropriate, the clinic will draw up an exercise programme to improve the patient’s strength and cardiovascular fitness and encourage any lifestyle changes, such as stopping smoking.

By the time the patient comes to surgery, appropriate arrangements should be in place for their care during and after the operation. This covers things like a personalised plan for managing their diabetes during surgery.

For the operation itself, the anaesthetist uses techniques that speed recovery. Avoiding high doses of morphine and other opiates, for example, may help avoid complications.

Patients then recover on the high-dependency unit or on the general surgical ward, depending on their individual needs. There, early detection of problems such as low blood pressure, anaemia and breathing issues lowers the risk of complications after surgery. Patients can go home sooner and their outlook is better in the longer term.

That’s the ideal. Such care is challenging to deliver even when resources are abundant. The focus of my research is finding ways to make it consistently available to all patients.

Making it work

My first steps were to establish a BCIP anaesthetic group, drawing members from trusts across Yorkshire, and to build collaborations with anaesthetic, surgical and other colleagues across the region.

We started by examining perioperative care across Yorkshire and Humber. We found wide variation, both in the resources available in different bodies and in the organisation of perioperative care.

Assessments before operations, in particular, vary widely. In some centres patients undergo a detailed functional assessment, are seen face-to-face by an anaesthetist and are supported through an exercise programme. In others, the resources available for preoperative assessment are much more limited.

In some trusts, all patients go to a high dependency unit after major colorectal surgery; in others, most patients are sent to a surgical ward.

We saw the same variation in the use of medicines to manage pain both during and after surgery.

There’s robust evidence associating high doses of opiate drugs such as morphine with complications after surgery. If the patient goes home still taking these drugs, they’re at greater risk of opioid dependence and even of dying earlier.

Alternative painkillers and techniques, such as regional anaesthesia, are available. But again, we found no consistent use of these across the area.

“Improvement science looks beyond ‘what works’ to consider ‘how it can work in the real-world context’”

So we made our first target improving the use of painkillers, and in particular opiates, in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal surgery. To do this, we took an ‘improvement science’ approach.

Improvement science looks beyond ‘what works’ to consider ‘how it can work in the real-world context’. It brings a set of rigorous methods to change healthcare at both the individual and system level.

This involves generating evidence-based tools and quality indicators that can be applied across the whole system – that is, in all participating hospitals.

It uses robust techniques based on psychology and theories of behaviour change and monitors change with appropriate data collection.

I did this work with colleagues in Leeds, including Dr Sarah Alderson, who is the Improvement Science lead for BCIP, and Dr Caroline Thomas, who is the NIHR lead for Anaesthesia, Perioperative Medicine and Pain in Yorkshire and Humber.

Most opioids are prescribed through primary care, by your GP or dentist for example. But a significant proportion are started in more specialist secondary care when patients need surgery.

Patients undergoing potentially curative bowel cancer surgery are at high risk of opioid-related complications and longer-term dependence.

Our awareness of both the need for opioid stewardship and ways of reducing opioid use during surgical admissions has been increasing.

The ‘opioid crisis’ and rapidly rising deaths related to prescription opioid use in North America have been a major influence here. Despite this, there are no agreed indicators to evaluate or improve quality of care for opioid prescribing during surgery.

As part of our aim to reduce opioid use around surgery, we worked with colleagues to identify key indicators of quality care that could be applied in every hospital.

First, we reviewed the literature on quality indicators for perioperative opiate prescribing. Then, we asked an expert group of clinicians, from inside and outside Yorkshire, and a group of patient experts to assess these indicators using a formal rating process.

The final step was to convene a group of local and national experts to agree a set of quality indicators. Working with this group we have produced an action toolkit that can be applied across all the organisations in the region, and beyond.

The challenge of ageing

But there’s another challenge in managing colorectal cancer: the ageing surgical population.

As people age, they often become frail. Frail people are up to nine times more likely to suffer major complications following surgery.

Frailty is now a recognised clinical syndrome in its own right. Frail patients have fewer physiological reserves and are less able to recover from major stresses such as surgery.

They generally have ‘sarcopenia’ – reduced muscle bulk – before surgery. This may decline further following the operation; indeed it might never fully recover.

A major operation that is successful in terms of treating cancer may still move the patient from being able to live independently to needing support in the community or even in a nursing home.

Not all older patients are frail. It wouldn’t be right, and is potentially discriminatory, to deny a patient surgery on the basis of age alone. Nor is frailty an absolute barrier to surgery.

With appropriate preparation and care, frail patients can survive and even improve after major surgery. However, it is important that the decision to operate is made in collaboration with each patient.

We want to put in place a toolkit to ensure frailty is part of preoperative assessment”

In some cases, the risk of surgery – even when it offers a cure for one serious condition – may outweigh the benefits.

The significant increase in life expectancy in the UK is a triumph for healthcare and for society as a whole. But, as the population ages, the challenge of delivering safe surgery to older patients is growing steadily.

An analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics from England published in 2019 showed that the average age of adult patients undergoing surgery is significantly greater than that of the general population.

Between 1999 and 2015, the number of patients aged 75 years or more undergoing surgery increased from approximately 545,000 to over a million. It’s predicted to reach 1.5 million by 2030.

In response, the past decade has seen the development of Perioperative Care for Older People undergoing Surgery (POPS) programmes.

POPS take a multidisciplinary approach to optimising the care of the older patient undergoing surgery. They require collaboration across a range of specialties and disciplines, and depend upon support both within hospital trusts and in the community.

There’s growing evidence that this approach improves surgical outcomes, supports older patients facing high risk surgery to make the best decision for them, and is cost-effective. Nevertheless, uptake of POPS varies.

Within the BCIP, we’re implementing a programme to ensure the timely identification of frail patients facing major surgery.

We want to put in place a toolkit to ensure that frailty is part of the preoperative assessment process and informs decisions regarding surgery.

We started by comparing surgery for colorectal cancer in Yorkshire and Humber with that in Denmark. The two have populations which are similar in size and age profile and a similar number of hospitals.

Our analysis showed that Yorkshire patients over 75 are less likely to undergo such surgery than their peers in Denmark. The effect is even more marked for those 80 or over.

70% of patients aged 80 years or older underwent surgical resection of their colonic cancer in Denmark; in Yorkshire, it was 50%.

The Danish experience shows that it is possible to assess frailty using data routinely collected in the course of cancer care. Such assessment is available for almost all Danish patients.

This data suggests that being frail increases the risks of surgery above and beyond the effects of age.

Frail older patients facing surgery need specialist assessment and care if they’re to see the best results. These assessments inform decisions not only about surgery but about the patient’s whole package of cancer care.

There are hospitals in Yorkshire and beyond already using this approach. In the longer term, we want to ensure that these assessments take place as soon as possible after a diagnosis of cancer.

The next great revolution?

Embedded in the University of Leeds’ strategy is the belief that impact comes from collaboration not competition. The work we’re doing on perioperative care brings together practice and research, disciplines and sectors, organisations from across the region and beyond.

Of course, the centre of all this collaboration is the patient and matching the care we give to what each individual needs.

Modern surgery has transformed the care of patients over the past century, improving both survival and quality of life for patients beyond all recognition.

Major operations inevitably carry significant risk, especially for older patients and for people who also have other medical conditions.

Delivering the greatest possible benefit from modern surgical advances depends on not only what happens in the operating theatre but on advancing and improving the care of the patient throughout their surgical journey.

Enhancing perioperative care is perhaps the next great revolution in care for the surgical patient.