Reimagining impact

Creating an entrepreneurial education that makes a difference

The desire to make a difference sits at the very heart of the University of Leeds’s new ten-year strategy. Its ambition is to train the next generation of global citizens and leaders – educating the problem solvers, innovators, collaborators and critical thinkers who can tackle the big issues. Richard Tunstall explains how connecting students to real-world experiences opens up their confidence as active problem solvers, and provides communities with a creative resource.

At a staff-student meeting, shifted online like so many due to the pandemic, one student was speaking when another suddenly said, ‘Hang on, don’t you know my friend from school?’

Soon we all established that not only did they know the same friend, they were studying the same course and in fact lived in the same hall of residence. But this wasn’t Freshers Week, this was the end of their first year at the University of Leeds. In all that time of remote learning, a new connection that would normally have been made in two days wasn’t made for seven months.

We’ve all become more familiar with networking technology during the COVID-19 pandemic. But we’re often reminded that we’ve lost many social connections.

Leaders of global companies fear that new recruits are missing out on their personal development: they don’t sit in on meetings with senior managers, they don’t have those taps on the shoulder and spontaneous corridor conversations. In schools, we’re told that pupils must catch up on missed lessons, but we hear less about the social contact they’ve lost and how that will be restarted, or even relearned.

Connections matter, and they matter in how we learn, not only through our sharing of knowledge, but in our sharing of experience – what’s known as ‘social learning’.

Student Caitlin Pharoah O’Reilly discusses her business idea with her mentor Jonathan Straight, founder of Straight PLC, as part of her Spark Enterprise Scholarship.

Student Caitlin Pharoah O’Reilly discusses her business idea with her mentor Jonathan Straight, founder of Straight PLC, as part of her Spark Enterprise Scholarship.

As children, our social learning often doesn’t come through planned experiences. It happens serendipitously, through a mixture of personal interests, spare time, and the ability to follow opportunities that crop up.

In the same way, career opportunities can arise through family expectations and networks or through activities undertaken by individual schools, such as access to careers advice, links to industry, or introductions to entrepreneurship.

For me, as a teenager, the stepping-stone to a fascination with how organisations work came in this way – not from a class but through setting up a games club at school. I reached out to a business for support and funding, and became deeply immersed in the conversations and negotiations that followed.

Years later, I’m Associate Professor of Enterprise at Leeds University Business School and still working on how social learning can underpin our potential for enterprising behaviour.

Under its new strategy, the University is committed to making a difference in the real world, both globally and in our own community in and around Leeds. I’m especially interested in finding ways of equipping our students with the skills and confidence to innovate in a way that will make a real difference – regardless of what subject they are studying or what their background is.

Students enter universities with a wide range of expectations and assumptions; these may enhance or decrease their potential to identify and capitalise on opportunities for personal growth and creating an impact. Understanding what drives motivation in students from various backgrounds will facilitate more diverse ways of supporting and engaging them.

Such support might come through institutional university initiatives. But it can also come through the tangible engagement of community stakeholders in students’ education and the visible impact of such interventions.

The shift to experience

In the 20th century, only a minority of the UK population accessed a small number of higher education institutions. In the 21st century, over half of 18-year-olds attend higher education.

Students arrive at UK universities from around the world, and go to many different destinations when they leave. Their negotiation with the world begins immediately when they arrive at university. This often starts in the subject choices they make, but the activities they engage in while they study, how they make sense of these experiences, and how they communicate them to others all play a part.

The focus of learning has shifted, from concentrating on the knowledge content that students receive to encompassing the attitude they take towards the situations they face. These are what we call ‘graduate attributes’ and mindsets.

To some extent, graduate attributes are nothing new. Traditionally, university education was seen as instilling critical thinking, analysis and reasoning, regardless of the subject studied. This is still true. But employers are now also looking for what might seem at first to be additional – even competing – attributes, such as team working, creativity and intercultural understanding.

One solution to this challenge is experiential learning. Here academic knowledge-content is still taught, but the way it is delivered is changed, as the skills and attributes we hope to develop in students are brought to the foreground through their firsthand experiences.

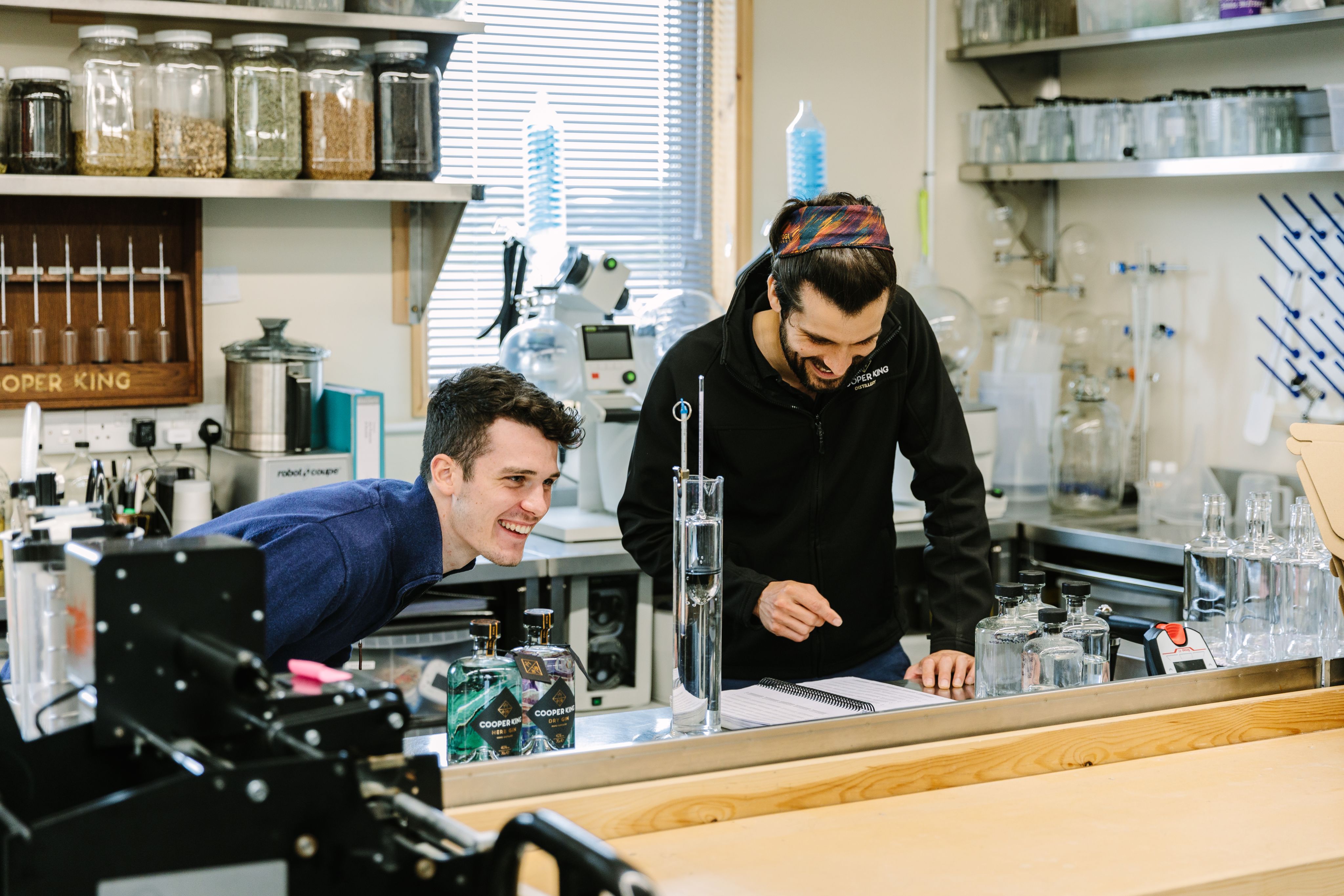

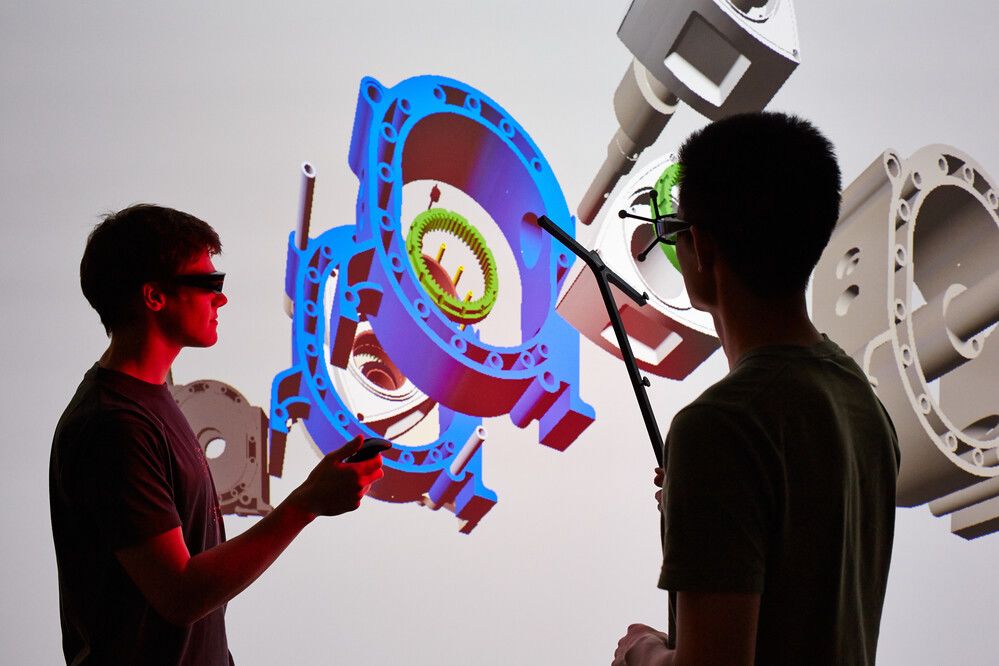

In the Centre for Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Studies at the University of Leeds, we start to look at attributes such as team working, creative thinking and interdisciplinary perspectives by deliberately designing courses to give students those interactions and experiences.

Research on leadership in entrepreneurial teams is brought alive through active and interdisciplinary working. Students experience for themselves how this can lead to better outcomes, bringing alternative perspectives together to come up with solutions which one person alone couldn’t achieve.

Student enterprise through practice

A group of medical students took an entrepreneurship module just after their return from time spent in clinical practice. Through activities in their course, they reflected on problems they’d noticed. Patients had often spoken about feeling ill not only because of their medical condition, but also because of all the devices attached to them in their beds. Working with others, the students identified a solution: wireless technology meant patients could still be connected to devices, but would no longer have to put up with the physical and visual sensation of wires and cables. The group went on to patent and license the technology for broader use.

Taking part

Developing these attributes doesn’t sit solely within the academic curriculum. It also happens in the wider experience of university life, through ‘extracurricular’ learning.

This might include classic student activity, such as taking part in student societies. But increasingly it comes through student-led volunteering in the community, research projects set up outside of class, working part-time during studies or through a placement, and even starting up a business while studying. In this sense, students lead their own learning, negotiating the options available to them in the world through extracurricular activity.

At the University of Leeds, we have developed support for students to begin that negotiation right away.

The Enterprise at Leeds initiative brings together not only different courses in entrepreneurship across faculties, but also Spark, the University’s professional student start-up support centre. Student-led enterprise societies and links to entrepreneurial alumni and local businesses further support these activities.

Achille Traore (centre), CEO of White Label Loyalty and Top Screen Media Ltd, meeting students as part of his role as Enterprise Ambassador for the Centre of Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Studies (CEES) at Leeds University Business School.

Achille Traore (centre), CEO of White Label Loyalty and Top Screen Media Ltd, meeting students as part of his role as Enterprise Ambassador for the Centre of Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Studies (CEES) at Leeds University Business School.

Through this networked approach to student learning, we aim to provide not just equality of activity, where all students have access to a promised list of modules, but also equality of opportunity, where all students with an interest in entrepreneurship and creativity can find different opportunities which interest them.

Crucially, this approach supports them from their own starting point, be that the student interested in being creative in a future job, the student running their own business while studying, or the student who wants to make an impact on their home community through starting a social enterprise.

Together, they can share challenges and ideas in their common objective to use the skills and attributes they are developing to make a positive impact on others.

Developing a coherent community strategy may mean engaging with external networks and programmes which can identify needs and support planning. The key is having a theme which unifies these opportunities and offers a gateway for students to engage from across disciplines to come together to address shared challenges – ones which they are passionate about.

Student enterprise through culture

Two theatre students at Leeds came from the same disadvantaged community. Living at home while studying, they recognised that many of their friends didn’t see university as an option and had no real aspirations to go there. Determined to challenge this view, the students devised a play based on their experience. They then established their own social enterprise to take the play into local schools in their community and support conversations about the choices available to young women there.

Making an impact

The opportunity to make an impact often starts where students see the opportunity to engage with the wider towns and cities in which their university is located.

Traditionally this may be driven by a student’s research project: interviewing or surveying members of the local population, or capturing other data, from pollution levels to travel habits, from museum use to the impact of arts on wellbeing. Other engagements may be driven by local needs.

During local lockdowns, for example, we saw sports societies spend time raising funds for local charities when their sports fixtures were cancelled. As more standard practice, we’ve seen small businesses offering students placements, or local schools taking on students as short-term teaching assistants.

Again, these engagements are often serendipitous, rather than planned, but they can go on to become a regular opening.

For students, one opportunity often leads to insights and experience that uncover further opportunities. One of my students, for example, developed an idea for a mobile app which he ran for a year. He then met an alumna at a University of Leeds enterprise event. She mentioned her business’s need for an improved app and offered him a short internship to solve the problem. Together with his previous experience, this later led to him getting a job at a leading global technology firm.

We call this kind of purposeful personal development a mindset: that is, a way of thinking and approaching problems. In this context, an entrepreneurial mindset is not a set of skills for starting a business, but more broadly a way of approaching problems that are focused on opportunity and solutions, on how to best marshal available means and resources at hand.

This is different from a problems-focus on ends and pre-determined goals, which may be developed from more causal, scientific thinking for problems with clearer boundaries.

Brought together, these ways of thinking allow students to not only accumulate and develop knowledge through their research-based leaning, but to also apply it creatively to social, economic or even scientific challenges through their experiential learning, developing deeper competencies which means they can respond to situation and context.

It’s not just students who find value in these engagements, it’s also those who they engage with.

Provided with access to students who are motivated to learn about shared challenges meant that, on my own courses, small businesses have been helped through seeking creative ideas from students in order to mitigate the impact of social distancing on their business.

In another example, a local charity’s project on improving engagement with donors led to members of the student team working with them through the course, volunteering to join the charity’s board longer term.

Initiatives like this are supported through Leeds University Business School’s Small Business Hub and the University’s central Placements office and Alumni and Development offices. They support community organisations and businesses in their own learning and development, while simultaneously supporting the students in theirs.

Each engagement should build on the last, instead of replicating it. These groups then provide the organisational framework for these forms of collaborative innovation.

Student enterprise through fresh thinking

A social enterprise, providing event space and based in a disadvantaged community in Leeds, lost significant revenues as social distancing affected physical events during the pandemic. They asked students taking part in a project module to look at alternatives for their business. As the students weren’t part of the business themselves, they were able to bring completely new ideas for how to utilise the space for socially distanced meetings and events that supported the local community. This led the business to rethink the way forward and how to continue the work they did to support their beneficiaries.

Such experiences develop students’ own sense of their abilities and the value they can create for others.

These forms of engagement – creating real-world impact – can boost both students’ skills development and resources available to local communities. But they go further, fundamentally changing how such activity is approached.

For local organisations, this may lead to new ways of doing business. They might build students into their processes as a form of crowdsourcing new ideas and analysis and as critical friends who can bring new thinking to groups and small businesses with lower resources.

For students, access to opportunities and chances to help others in a structured way shifts the terms of engagement from informal learning and skills development, to more formally designed experiential learning and the development of a new entrepreneurial mindset.

Such experiences develop students’ own sense of their abilities and the value they can create for others.

The global pandemic has created challenges that will require all of civic society to address. Higher education has a vital part to play in this.

A university like Leeds can generate impact not only for all of its students, regardless of background, but also for the communities in which it is located. Through its innovative strategy, the University is actively seeking to be part of that answer.