Preventing atrocities

How together we can take on this global challenge

The Rohingya in Myanmar, the Uyghurs in China, and the Yazidi in Iraq – the last few years have seen the dramatic resurgence of violent atrocities across the world. Such crimes generate massive human suffering, with enormous global impact. After the Holocaust of the Second World War, we promised ‘Never again’. Cristina G. Stefan asks, what does it take for the world to act together to stop such atrocities? For that same promise not to be uttered again – and again, and again?

Atrocity prevention is one of the most urgent and demanding global challenges of our times. In the span of only a few months in 2021, atrocity crimes fuelled crises across the world, from Myanmar to Xinjiang in China and Tigray in Ethiopia.

Shocking headlines are constant reminders of these atrocities. It can feel overwhelming. But I believe that each of us, as citizens of the world, can contribute to addressing the most pressing challenges we face today. And this is precisely what I tell my students when we discuss the politics of global challenges in class.

This is where working at a ‘university without walls’, as the University of Leeds’s 2020–30 Strategy puts it, helps enormously.

I teach international politics in the Department of Politics and International Studies (POLIS) at the University of Leeds. Under its new strategy, Leeds is focusing its research on tackling the world’s biggest challenges, extending the University’s reach and delivering worldwide impact.

As challenges come, atrocity prevention is one of the world’s toughest. Mass atrocities not only cause immediate and severe harm. They can generate tremendously long-lasting adverse effects on economic, political, social, and cultural development.

The multi-generational, long-term effects of gross violations of human rights are increasingly recognised as one of the main obstacles to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the target date of 2030.

The SDGs provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and our planet. All 17 SDGs were adopted by all UN member states in 2015. They represent an urgent call for action for all countries across the world working through a global partnership.

Backing up its strategy, the University of Leeds has committed to SDG 17: Partnership for Goals. This makes it clear that without partnerships – both within and outside academia – there will be no progress towards tackling the global challenges we are facing today. That includes the immense challenge of preventing mass atrocities.

‘Never again’?

Over a century of atrocities

Since 1900, on average, nearly two mass atrocities have begun every year, all across the world.

Mass atrocities amount to large-scale violence targeting unarmed populations in times of war or peace.

Genocide is the most familiar example, but atrocities also include war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

No region is immune from the risks of mass atrocity crimes.

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, between 40–50 countries have either experienced atrocities or have been at serious risk of atrocities. Millions of people have been killed or displaced.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the international community engaged in steadfast soul-searching to find a global consensus on how to react to gross and systematic violations of human rights.

This came after the UN’s abject failure to prevent atrocities committed in the 1990s in Rwanda and the Balkans, as well as NATO’s 1999 military intervention in Kosovo. The latter had occurred without authorisation by the United Nations (UN) Security Council, so was deemed a blatant violation of the UN prohibition on the use of force.

The controversies of the 1990s, however, relate to some of the hardest questions in international law and politics, the kind of questions I challenge my students to engage with and discuss.

How should the international community, either collectively or through individual states, respond to widespread and appalling abuses of human rights?

How should the norm of non-intervention – the pinnacle of international law – be balanced against the need to protect the human rights of vulnerable populations?

Should force be used to prevent atrocities from happening or to halt human suffering, and if so, under what moral, legal, and political authority?

In 2000, the UN Secretary-General called for a global consensus on how to respond to mass atrocities. In response, the Canadian government assembled the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS).

The task was to find a new framework for the world to respond to atrocities, acting through the UN. The result was the Responsibility to Protect, usually referred to as R2P.

R2P thus emerged out of the failures of the UN Security Council to act collectively in response to the mass atrocities of the 1990s. This set of principles became official UN policy after its unanimous adoption by the United Nations General Assembly at the 2005 world summit.

R2P is a global political commitment to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

It has three pillars: the responsibility of the state to protect its population, states’ pledge to assist each other in these protection responsibilities, and states’ commitment to take collective action to protect any country’s population where that country is failing to do so.

R2P, however, has not been uncontroversial. Criticisms have surfaced in national, regional or international debates about its implementation. These are mostly related to its effectiveness and how it infringes upon national sovereignty, notably in that it could sanction military intervention by some states over others.

But R2P does provide the most comprehensive political framework we have at the moment for preventing and responding to mass atrocities.

My eureka moment

In 2002, a few months into my PhD at Western University in Canada, I came across the Responsibility to Protect while acting as a rapporteur for an international conference organised by Global Affairs Canada in Ottawa.

This was a eureka moment for me. I became absolutely fascinated by this powerful new idea and its potential to prevent atrocities and trigger action when we need to protect the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Could we, as an international community, have finally found the framework to prevent and stop atrocities, once and for all?

This is when and how I found my cherished PhD dissertation topic, which assessed whether R2P – as a framework of protection – provided an effective alternative to the political, ethical and legal dilemmas raised by the concept of humanitarian intervention.

Two decades later, this one topic continues to be the driving force behind my scholarly work.

In 2017, I learned a lot about the real-life application of my own research on atrocity prevention when I was seconded to the UN Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect in New York.

The most important lesson was that prevention is always context-specific, regardless of the general tenets of the R2P framework.

This secondment was made possible by the value that my own workplace, the School of Politics and International Studies (POLIS) at the University of Leeds, places on increasing the breadth and depth of partnerships with our key partners.

It was funded by the POLIS strategic research investment fund. POLIS also supports my work with other partners outside the university sector who can have a real impact.

How partnerships tackle global challenges

Research and education play a key role in working towards reaching the United Nations’ SDGs.

The University of Leeds has signed the SDG Accord, the university and college sector’s collective response to the SDGs.

In doing so, Leeds is recognising the role of education in delivering the SDGs and the value that brings to wider society. But we can’t achieve this without unparalleled collaboration across institutions, states and research centres.

I’ve always actively pursued working with partners within and outside academia. I’ve collaborated with colleagues from both the Global South (for example, the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro) and the Global North (for example, the University of Southern Denmark).

We need this balanced worldwide perspective when addressing pressing global challenges like atrocity prevention.

But I wanted to take this further, since I believed we needed a strong foundation for building the research community around R2P. This was especially the case in the UK, and so I co-founded the European Centre for the Responsibility to Protect (ECR2P) at the University of Leeds.

This occurred in 2016, the year the World Bank reported more countries experiencing violent conflict than at any time in nearly 30 years.

In launching ECR2P, our goal was to reduce atrocity risks by providing research-based evidence to states and international organisations in their efforts to protect populations from mass atrocities.

As a centre of expertise, ECR2P explores the role that politics, ethics, and the law play in addressing worldwide inequalities in the prevention of, and protection from, mass atrocities. We do this by covering six thematic research agendas that fall under the UN’s SDG16.

Our multidisciplinary research investigates peace, justice, security, and the need for strong and responsible institutions to put R2P into practice, when needed.

But we must also look to build partnerships outside of academia. This means collaborating with key NGOs that place as much importance on atrocity prevention and R2P as ECR2P does, such as Protection Approaches in the UK.

What about partnership outside the university?

Of course, individual researchers can have a direct impact on policy and practice.

One example from my own experience is a report I wrote for the UN Office on Genocide Prevention and R2P on ‘Lessons Learnt from Guinea’.

Learning from what has worked to reduce the risk of atrocity crimes reoccurring after the 2009 stadium massacre in Conakry, Guinea, this showed that the UN could employ a specific combination of preventative, diplomatic, political and juridical tools when similar risk factors arise elsewhere.

In my collaborations with the UN Office, I also argued for an increased role for non-permanent UN Security Council members and for the inclusion of alternative R2P views, such as those of Brazil and others from the Global South, to consolidate R2P’s legitimacy and support.

This helped broaden the consultative processes that shape UN member-state policies and perceptions of R2P. It also brought empirical evidence towards better legitimating R2P policy development.

But it’s our work at ECR2P that shows the magnifying power of international collaborations.

There are two other global centres looking at R2P – the Global Centre for R2P in New York, USA, and the Asia-Pacific Centre for R2P in Brisbane, Australia.

What distinguishes ECR2P is its emphasis on pragmatic policy reform. We seek to locate policy changes that will trigger incremental and achievable reform to atrocity prevention policy. Often, we are working in areas that have been previously overlooked.

For example, ECR2P research has provided insights on R2P-related developments in Libya, Syria, Myanmar and other mass atrocity situations. These have informed evidence to a number of UK select committees and UK-based institutions working on protection, prevention and R2P.

Such insights stem from a body of research analysing how and when military intervention may play a role in R2P implementation, and how states and the UN can respond effectively within the R2P framework and international law.

We go further and play a proactive role. As one of the founding members of the Atrocity Prevention Working Group in the UK, we regularly call on the UK government to engage in atrocity prevention worldwide.

We also draw attention to cases with increased risks to ethnic minorities and human rights violations, as seen in places like China and North Korea.

Partnership is always two-way: informing and learning.

Alongside ECR2P, I also launched the ‘Women Network on the Responsibility to Protect, Peace and Security’, with the support of the British Academy.

This global network highlights the excellent work and impact of established academics and researchers, experienced diplomats, United Nations and European Union officials, seasoned policy-makers and practitioners, civil society and charity directors – all women – in the international peace, security and the R2P fields.

But it also brings these experts together with female Early Career Researchers, so that the latter find inspiration in the former’s research and work. They also learn about ways to generate impact, so as to make their research relevant to the real world and to decision-makers facing hard choices related to prevention of, and protection from, atrocities.

Such partnership with external bodies is always two-way: informing and learning.

Perhaps my collaboration with the UN Office best illustrates this. My research informs its policies. But, as a researcher, I also learn what UN practitioners expect to see in my evidence-based research, and how the theoretical concepts I address in detail apply to real-life cases on the ground.

Pursuing such a two-way partnership feeds into an ongoing and spreading sense of community. Each year since the launch of ECR2P, for example, the acting UN Special Advisor to the Secretary-General on R2P has delivered our Centre’s Annual Lecture.

In 2018, the UN Special Advisor on R2P was Ivan Simonovic, formerly Assistant-Secretary-General for Human Rights of the United Nations. He loved his visit to the University of Leeds so much that he generously accepted a two-year Visiting Professorship at Leeds.

During this time, he gave several lectures on atrocity prevention to our POLIS students. He spoke candidly about the challenges he faced in implementing his R2P mandate at the UN, giving students real-world insights from the highest level.

One of Simonovic’s legacies as UN Special Advisor was an Atrocity Prevention Summer School, bringing students from four continents together to learn about atrocity prevention and R2P.

Alongside Ivan Simonovic and three experts from Australia, Denmark and Croatia, I’ve been one of the five course directors who designed and taught on this international programme.

This Summer School is now offered each year at the Inter-University Centre Dubrovnik. It’s a unique opportunity, which brings students from the University of Leeds to study together with students from USA, Denmark, Germany, Croatia, Ghana and Australia.

And all this comes back to working with my students in class and asking them those challenging questions on the toughest global challenges of today.

They are the global citizens of tomorrow, and ultimately they are the people who will tackle atrocity prevention worldwide.

Working in partnership with global universities and technology partners to co-create community-based, open, and collaborative education is at the very heart of this.

And it’s at the centre of the University of Leeds’ new strategy, which sets its ambition as training the next generation of global citizens and leaders, educating the problem solvers, innovators, collaborators and critical thinkers who can tackle these big issues.

So much still to do

There has been some progress since 2005, when UN member states committed to end the most egregious human rights violations through the R2P framework. Yet so much remains to be done.

Millions of people from various ethnic or religious groups are – today – fleeing violence targeted against them, often by the very states that are supposed to protect them.

We read about devastating instances of human suffering in parts of the world where atrocity crimes continue to be committed with impunity.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated existing problems that affect the most vulnerable populations across the world – including xenophobia, forced returns of refugees, discrimination against certain groups, and hate speech.

Despite the existence of R2P, atrocity crimes continue, putting international peace and security at risk.

The war in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, for instance, has been going on for months, without any successful attempts, to date, to stop atrocities committed against civilians.

Thousands of unarmed civilians have been killed and wounded, more than 2 million people have been displaced, and military forces have systematically raped women and girls.

The humanitarian consequences are devastating: over 5 million Tigrayans need aid to survive – aid that has so far failed to reach them.

Without doubt, this is a crystal-clear example of where R2P should be applied but has not yet been so.

Only one month after the February 2021 coup in Myanmar, the UN special rapporteur for human rights there acknowledged that the brutal response to peaceful protests was likely meeting the legal threshold for crimes against humanity.

So far, the UN Security Council has only issued a statement condemning the bloodshed and calling for “restraint, dialogue and full respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms”.

What’s needed is a resolution calling for targeted sanctions, arms embargoes and referral to the International Criminal Court.

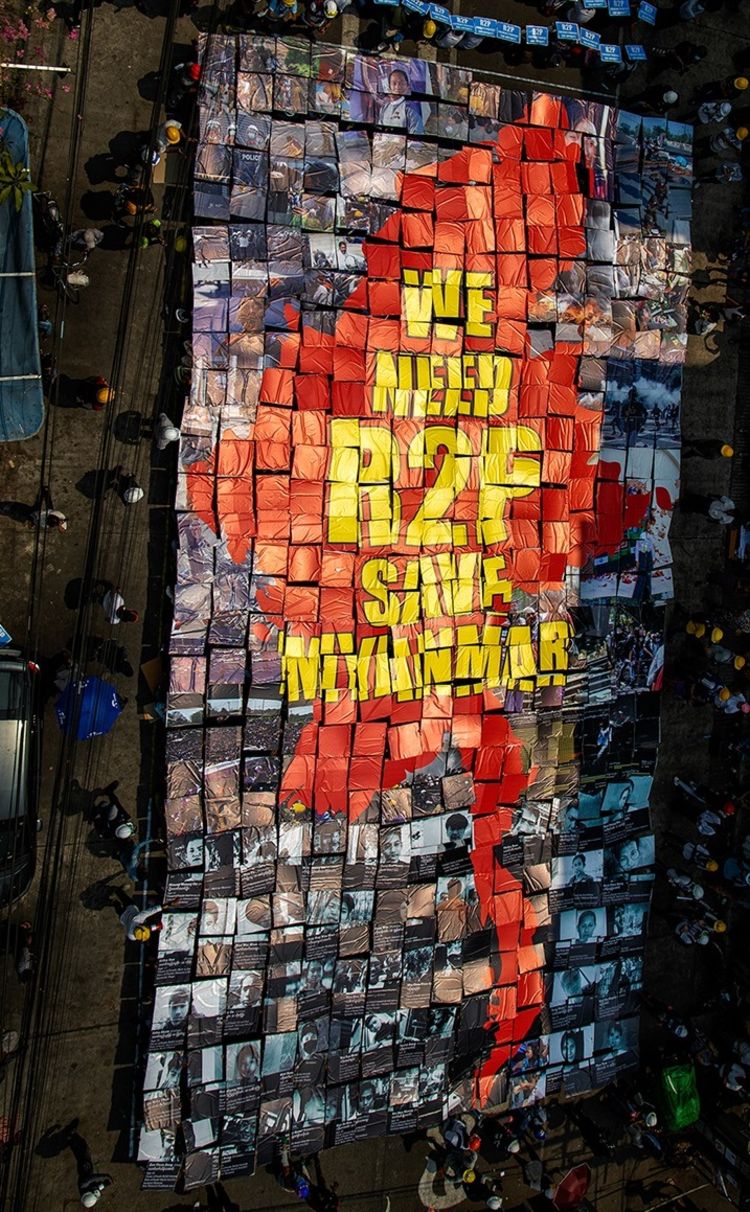

Civilians across the country have been begging for R2P to be implemented. Their placards and messages are written in English, even though only 5 per cent of the population speak it. They are using the universal language for the world to see their pleas and to act.

Protestors holding placards asking for R2P to be applied in Myanmar. Image: © Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Protestors holding placards asking for R2P to be applied in Myanmar. Image: © Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Never before has the world witnessed so many desperate and active calls for R2P implementation from vulnerable people targeted by their own government’s forces.

One day – or day one?

We are witnessing ever more atrocities against civilians in ever more corners of the world. And so, progress on atrocity prevention is only possible if we unite our efforts towards changing the status quo.

We each attempt to make a positive difference in the world. And we contribute towards tackling global challenges, as small, individual components of much bigger, global efforts to translate knowledge into action. But it needs all of us to take part.

Ultimately, it really is up to each of us individually, as global citizens of the world, to decide if this is ‘day one’ of attempting to make atrocity prevention a reality or whether we continue to postpone this to ‘one day’ in the future.

We each carry with us our own individual responsibility to protect.

Only when we collaborate, and when we build partnerships, can we make a difference and ensure that we are able to say ‘Never again’ – once and for all.