Not ‘hard to reach’ but ‘hardly reached’

Empowering communities by engaging them in research

When Jasjit Singh was researching media portrayals of British Sikhs, he wanted to make sure his research was a true representation of the people whose lives he was talking about. Working with the community then gave him the authority to take the findings forward to influence national and international policy.

Here, he reflects on how universities can raise the profile of ‘hardly reached’ communities.

By explaining how research works and embedding open dialogue in their projects, academics can make sure their work is relevant – and that it will make a real difference to society.

I remember once returning late from a meeting in London and getting a taxi home from Leeds station. As we passed the University of Leeds, I mentioned to the taxi driver that this was my place of work.

“Oh”, he said, “I’ve driven past here so often. It’s a huge place. Always wondered what goes on in there. Presume it’s just like a school?”

For many, universities are simply places where students study for degrees. At the time, I wondered how universities could better highlight their role as repositories and generators of knowledge. How could they engage with the public? How can they show how knowledge generated from research can change society for the better?

As a sociologist of religion, I regularly use interviews and focus groups to understand people’s perspectives on the topics I research. When I’ve been invited to present at community events, I’ve found that, as well as speaking about a particular research topic, I’m also often informing the audience about the importance of research and of the research process.

This has led me to think about the construction of knowledge, the role of academia and the place of the university in society. How can universities and the work that goes on in them make a difference beyond the university walls?

This question is at the heart of the University of Leeds’ new ten-year strategy. It’s one that has significantly influenced my academic journey. Since completing my doctorate in 2012, I’ve actively sought to enhance my profile not only as a researcher and educator, but also as an academic who engages with community in the broadest sense. It’s led me to work regularly with non-academic communities and organisations. I want to understand what issues matter to them and how research could provide insights into these.

Ultimately, I want my research to make a real difference in people’s lives.

Reaching out beyond the University walls

My career as an academic began back in 2007. I was working full time in IT then. In the evenings and at weekends, I was writing an MA dissertation on how young Sikhs were managing their religious identities.

After my MA, I was asked if I had ever thought about studying for a PhD. This wasn’t something I’d really considered before. Although I’d been to university, no-one I knew had a PhD or worked in academia, so I had no idea what this would entail.

At that time, the AHRC/ESRC Religion and Society programme had launched a call for collaborative research projects with external partner organisations. So I reached out to local and national Sikh organisations to see if we had any areas of mutual interest.

It turned out that the British Educational and Cultural Association of Sikhs (BECAS) was also interested in understanding how young British Sikhs were learning about their religious and cultural heritage.

Having successfully applied for the scholarship, I gave up my comfortable, well-paid job to become a full-time doctoral researcher. The opportunity to spend time researching Sikhs in Britain really appealed, even if the salary reduction didn’t!

Developing the potential partnership put the onus on me to explain the value of research and the role that universities play in the production of knowledge. I met with the BECAS committee several times during the application process to explain how the research process worked and to ensure that the research questions we were developing were relevant to both myself and BECAS.

Working with a non-academic partner like BECAS helped me create relevant research questions and areas of focus and ensured I was taking account of their interests and perspectives. For instance, while I was mainly interested in events being organised by young Sikhs, BECAS were more concerned about the role and effectiveness of Punjabi language supplementary schools held in Sikh Gurdwaras, which I then incorporated into my research.

Throughout my work since then, I’ve continued to experiment with ways of producing knowledge and learning that help empower non-academic audiences.

My most recent project began after I’d seen numerous media headlines about the activities of Sikhs in Britain which were often being linked to ‘radicalisation’ and ‘extremism’. I wanted to understand how real this framing was, and the context for it.

My research began in a traditional way: I dug into the archives and carried out extensive research on how the media and policy makers had talked about Sikh activism. I also interviewed individuals who identified as Sikh activists. But, once I’d drafted my report, rather than simply publishing it, I first wanted to present my emerging findings to the Sikh community for feedback.

Using my experience working with non-academic audiences – which had begun with BECAS during my PhD, and which continued with me engaging with South Asian arts organisations on my research on the cultural value of South Asian arts – I reached out to Sikh organisations, using my existing contacts and social media.

I’ve long made a point about talking about my work and about Sikh issues, particularly on social media and through platforms like The Conversation.

This strong presence on social media helped me approach key stakeholders in the Sikh community. I asked if they’d be interested in hosting events for me to present my findings to local groups.

The Sikh Education Council hosted the first event in July 2017 in a hotel in Central London.

This event quickly sold out and attracted members of other Sikh organisations including the Sikh Press Association. This helped with arranging future events including in Southall, which the Sikh Press Association arranged in Sept 2017. I also presented at a Sikh conference in Warwick and in Leeds in Oct 2017.

These events were all open to the public and attracted attendances ranging from fifty to one hundred people at each. Once the discussion began, we followed ‘Chatham House rules’ – no live streaming, no tweeting and so on – to ensure that everyone would have the confidence to speak freely.

The research findings were presented to local communities for feedback before final publication.

The research findings were presented to local communities for feedback before final publication.

At these events I explained my research process and asked for feedback on the findings before publication. The community welcomed this transparency. Jasveer Singh, of the Sikh Press Association, noted that such levels of transparency and interaction were “the right way forward for real and authentic insights into the Sikh community”.

These events were helpful in several ways.

First, they started a conversation about my research, and demonstrated the processes I was going through to develop my findings.

Second, they enabled members of the very community which the research was about to feed back on the findings before publication. This was commented on in the feedback, with one attendee at the Southall event stating:

“This is the first time that I’ve seen this kind of engagement between the community and academia.”

Attendees critiqued some of the terms used, wanted to know more about research funding and challenged some of the findings. It was particularly valuable for me to respond to these challenges in public to a Sikh audience, to explain how I had developed my findings and to, where necessary, consider how the final report could address some of these concerns.

Overall, by presenting to the Sikh community in London, the Midlands and Yorkshire, I ensured that key members of the Sikh community in Britain were aware of the research process I had been through to develop my conclusions and could therefore act as advocates for the research.

To ensure that it was readily available, I published my final findings as a freely downloadable open access report.

Having an impact in the real world

As one of the first in-depth analyses of Sikh activism in the UK, the report has become a key resource for policy makers addressing Sikh issues. Rather than sitting on university library shelves, it has fed into various levels of governance in the UK, including the Home Office, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), and various counter-extremism agencies.

“Having robust and credible research has been of great benefit to a number of Government departments in the increasing understandings of Sikh issues,” according to Garinderjit Manik of the Home Office Sikh Association.

And this impact has continued long after publication. I’m often asked to present at other events, where policy makers want to understand the context and dynamics of the Sikh community in Britain. Most recently for example, I’ve given oral evidence to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Religion in the Media.

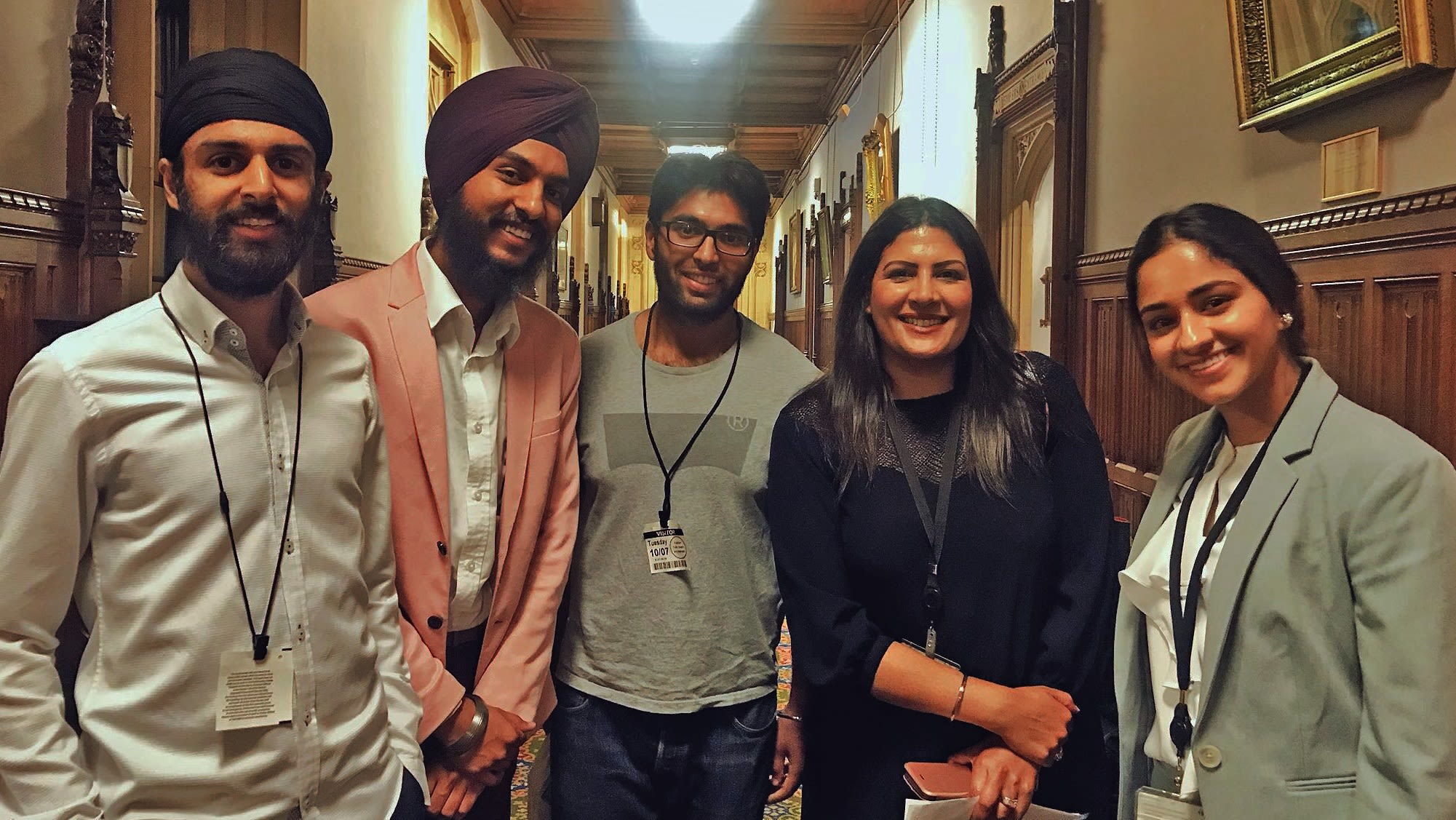

The findings have fed into policy making: here at the All-Party Parliamentary Group for British Sikhs

The findings have fed into policy making: here at the All-Party Parliamentary Group for British Sikhs

On its publication in November 2017, the report also received substantial coverage in mainstream British news media and current affairs programmes, including BBC Radio 4 and the BBC Asian Network.

More surprising, however, was the unprompted engagement from international media, including the Panjab Times, Malaysia Asia Samachar and the Times of India. It was promoted by Sikh media and educational organisations, including Basics of Sikhi and Naujawani and enthusiastically discussed on Sikh TV channels such as Akaal as filling a huge historical gap for Sikhs in diaspora.

Appearing on mainstream national media meant I built a strong media profile as one of few academic commentators on Sikh affairs.

Once again, this led to other opportunities for my research to have practical impact. I was asked to join the advisory board of the Religion Media Centre. This in turn has led to invitations from several media organisations. REACH PLC, the largest national and regional news publisher in the UK, asked me to train journalists about Sikh issues. And the report has its own specific impacts. OFCOM has used it to assess whether a Sikh television station had breached regulatory guidelines, for example.

It’s a snowball process. All this coverage again increased the profile of the research, leading to invitations from international organisations.

In 2019, the World Sikh Organisation invited me to headline a series of panel discussions in Toronto, Edmonton and Vancouver on the representation of Sikhs in policy and media. These events attracted large and diverse audiences, including Parliamentarians and leading community figures.

The Sikh Press Association used the report in a successful complaint to Canada’s National News Media Council against the Toronto Sun about the incorrect representation of Sikh concepts in a newspaper article.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, my research engagement has empowered Sikh communities and organisations. Providing prominent open access resources and facilitating open dialogue community events has helped foster greater community cohesion and education.

Local Sikhs attended one of the initial community consultation events in Leeds. They decided to use this model of engagement to establish the Sikh Alliance Yorkshire (SAY).

SAY has gone on to hold similar open community consultations with policy makers on a variety of topics, including mental health, hate crime and bullying, and loneliness among Sikh elders.

For SAY’s Co-Chair, Rashpal Singh Sagoo, “using that same model, we thought well, let's build on that and create our organisation, Sikh Alliance Yorkshire, to do that same kind of thing.”

When I was first searching the archives for newspaper articles, I had no specific thoughts to address MPs or train journalists. Choosing to involve the community in my initial findings gave me the authority and confidence to talk to the media and to policy makers about my findings. My research has a life way beyond the library. It has not only improved our academic knowledge, it has made a difference in society at home and abroad. I couldn’t have planned precisely for any of this. But opening doors to the community opened other doors for my research to have real world impact.

Jasjit Singh uses YouTube to make his research more accessible (13 mins)

Engaging the community

It’s common for certain communities to be labelled as being ‘hard to reach’.

But communities are only ‘hard to reach’ if we fail to reach out and engage with them.

In fact, rather than being ‘hard to reach’, many communities are ‘hardly reached’. It is surely part of our role as academics to tackle inequalities by helping to raise the voices of these groups.

How can we do this? Much of it is about building trust and expectations, so it’s important we allow ourselves the time to develop meaningful, sustainable relationships.

By facilitating opportunities for engagement, communities can become part of the research process rather than simply being targets of research. Having meaningful relationships also helps ensure that academics have evidence for the claims they make, and that they are up to date with relevant issues when asked to speak about the communities they research.

The most fruitful relationships develop when both parties have properly considered why they wish to engage.

Overall, I’ve learned that engagement needs to be driven by values: the most fruitful relationships develop when both parties have properly considered why they wish to engage.

It’s necessary to listen and understand the issues of importance to partners, and to understand these issues from the point of view of communities themselves.

Working with trusted individuals and/or with trusted community organisations is a powerful way to prompt two-way dialogue. But this does require time and effort to establish.

As academics and researchers, we often work with several public groups and external partners, including media and policy makers. We’re therefore in privileged positions to bring these different types of audiences and organisations together. We should use our privilege more to do this: lifting the voice of others can only enrich our research.

As academics, we should authentically engage with members of the communities we research. Image: World Sikh Organization panel discussion at Surrey City Hall.

As academics, we should authentically engage with members of the communities we research. Image: World Sikh Organization panel discussion at Surrey City Hall.

Developing research projects in collaboration with external partners can also lead to better questions and more meaningful research. It’s important to start such conversations early.

Researchers must also manage expectations, particularly around timescales and funding. The timescales for funding awards in academia may be longer than many community organisations are used to.

Researchers must also recognise different types of knowledge and different types of expertise. As ‘academic experts’, university researchers are often called to provide expertise to policy makers and media. I’ve done this on numerous occasions.

But I’ve only felt that I could do this authentically because I have engaged with members of the communities I research throughout my research.

So, where do we find the University community?

These outcomes link directly with the new University of Leeds strategy which focuses on the themes of culture, community and impact.

The community-centric methods of engagement I’ve developed illustrate how academics can empower communities by embedding open dialogue, by explaining the process of research and by enabling communities to co-produce research projects to help them address issues of relevance and concern.

Rather than seeing themselves as international first, national second, and local third, universities could engage with all these communities.

These are all important considerations for universities in the future. Rather than seeing themselves as international first, national second, and local third, universities could refocus on engaging with all these different types of communities, particularly the local.

Local communities will view their local university with pride if the university activity aligns itself with civic needs.

In terms of community engagement, universities could ensure that the views of local people and communities are reflected in their formal governance and communications structures and strategies. Each could consider how it works with other local institutions to maximise its impact in society.

The University would then ensure it remains relevant to local communities, so that a taxi driver driving past knows exactly what goes on in there and is aware of the value of the research produced. They might even tell their passengers all about it!

My position and privilege as an academic, and the fact that policy makers and media will take note of what I say because of my expertise, means that I have a responsibility to highlight the issues and interests of the communities I research.

Both by influencing policy and through my public engagement and impact activities, I’m committed to demonstrating the value of Arts and Humanities research. I want to raise its profile among groups – at whatever level – who may not have previously engaged with these disciplines.

As I’ve explained here, many of my research projects have been developed in collaboration with communities outside academia to ensure that the research findings are of immediate relevance. Working with these groups has allowed me to challenge inequalities by raising the profile of these voices.

It’s so important that we do not simply highlight the same old voices. Rather we must do what we can to amplify the voices of these ‘hardly reached’ groups.