What if the drugs don’t work?

Solutions start with communities

Infections that would have quickly killed us a hundred years ago are rarely a cause for concern nowadays. Antimicrobials protect us from infections caused by microbes such as bacteria, fungi and viruses. But the speed at which microbes are becoming resistant to these drugs is accelerating rapidly. What will happen if the drugs stop working? Jessica Mitchell is exploring effective ways for our communities – global, national, and local – to come together and respond.

The past year has made us all too well aware of how microbes can change. New variants of the COVID-19 virus continue to have a profound impact on our daily lives. Vaccines developed so impressively after the first wave of the virus may not prove so effective as newer variants arise.

All microbes naturally evolve and change: they are living things and respond to stresses around them. Some of these changes mean that microbes can survive the treatments we use to fight the infections they cause. This is called antimicrobial resistance, or AMR.

Alongside COVID-19, we are also undergoing the ‘silent pandemic’ of AMR. Microbes, especially bacteria, are rapidly evolving resistance to our antimicrobial treatments. Humans are accelerating this process, because we often use antimicrobials in the wrong way.

We take them when they’re not needed, we don’t match the right drug to the right bug, or we fail to finish full courses of treatment. All this gives microbes a chance to figure out how to survive these drugs, developing antimicrobial resistance, or AMR.

If we don’t change our behaviour, we are looking at world where common infections could once again become killers. Routine surgeries, like caesarean sections and knee replacements, will become much riskier because of the potential of picking up a life-threatening infection.

After several years reviewing the state of AMR, including its financial and humanitarian costs, Professor Jim O’Neill has concluded that we must act this decade to prevent catastrophic death tolls and economic shocks relating to AMR.

But we all use antimicrobials in different ways, not just for our own health but for that of our families, livestock, and pets. How do we change the behaviour of the 7 billion people on this planet?

Initial training

I initially trained as research zoologist. I spent several years in sub-Saharan Africa working on small mammals, including meerkats and banded mongooses. My specific interest in AMR began after one of my projects showed that banded mongooses change their behaviour to avoid individuals with high parasite burdens.

I became interested in thinking about how the mongooses’ proximity to humans may influence their parasite burdens and other microbial infections. AMR is only just being addressed as a ‘One Health’ problem, but human use of antimicrobials inevitably reaches wild animals. One day, I very much hope to consider the impact of AMR on wild animal populations like those banded mongooses.

During my time in Africa, I was often based in remote, rural settings. There I got to know local communities living around the wildlife and started to engage with them on the challenges of balancing human development with healthy wildlife communities. Alongside my main research, I got involved with other projects.

One exchanged knowledge with school children on the behaviour and needs of their local wildlife; another tested the use of fence-mounted beehives to deter elephants from eating crops. Both projects used very different methods of community engagement and from these I developed a new appreciation for social science research methods, methods I now rely on.

Now, I’ve brought these two interests together. As well as leading my own research project and supporting others, I also co-lead the CE4AMR network, alongside Dr Rebecca King and Professor Paul Cooke. CE4AMR is a global group of research projects using community-based approaches to tackle AMR.

Building on my experience, I believe we need to move away from treating AMR as a medical or scientific problem. Instead we must consider its social dynamics, particularly how best to communicate information, risks and solutions.

We do have experience in tackling such big global challenges. The world is now uniting in its understanding that human behaviour must change in order to prevent the climate crisis.

A large proportion of climate crisis research about changing our behaviour centres on community engagement – or CE. This is the process of learning from communities to create locally meaningful solutions. My work at Leeds University takes the learning from community engagement projects aimed at the climate crisis and applies it to fighting AMR.

I aim to understand how successful CE approaches to the climate crisis could be reworked to address AMR with maximum impact. I want to find accessible and meaningful ways to engage with this challenge across the local, national, and global community.

So, what do I mean by ‘climate crisis’?

This term refers to the current state of highly dangerous and irreversible changes to the global climate. The root cause of these changes is the over-use and exploitation of natural resources, including fossil fuels like oil, gas and coal. Humans began to extract these resources on an industrial scale just over a hundred years ago.

The process has caused massive damage to natural habitats and ecosystems. Animals and indigenous communities are often displaced to make way for mines and extraction plants. Natural water ways and soils are polluted by waste products. The burning of fossil fuels for energy releases harmful biproducts such as ‘greenhouse gases’ like carbon dioxide These build up in our atmosphere and create a warming effect like the glass panels of a greenhouse.

This heats the planet, leading to changing weather patterns and increasing temperatures, which in turn bring flooding, melting icecaps, and rising sea levels.

… And what exactly is AMR?

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is the process by which microbes change to resist the effects of antimicrobials, including those found in nature and our commonly used manufactured treatments such as antibiotics. AMR is a natural process; some microbes just happen to be resistant to certain antimicrobials. Other microbes can develop resistance through changes in their DNA.

This happens when the microbe is subject to stress such as changes in temperature, radiation, pollution, competition with other microbes – and the use of antimicrobials. If antimicrobial drugs are not properly matched to the infecting bug, for example, or if they are taken for longer or shorter periods of time than recommended, they can stress microbes without killing them. This can lead to AMR developing – which could make future infections much more difficult to treat or even life threatening.

AMR is already responsible for 700,000 deaths a year; unless we act soon, this could rise to 10 million.

AMR is already responsible for around 700,000 human deaths a year, according to Professor O’Neill; unless we act in the next decade, he warns, this could rise to 10 million. Because AMR occurs in micro-organisms, it can spread throughout our natural environment, reaching wildlife, crops, and domestic animals.

The potential impact is frightening. Unchecked, AMR in livestock and crops could decimate food supplies. Waste antimicrobials can spread quickly through soil and water, reaching many new areas. On this journey, their interactions with naturally occurring microbes could cause resistance to develop. These resistant microbes can then infect humans and animals, causing infections which are difficult to treat. This could devastate wild animal populations, especially if natural antimicrobial defences fail. This could lead to species extinctions and even ecosystem collapse.

Antimicrobials can move between species

Antimicrobials can move between species. New infections in farm animals usually result in large-scale antimicrobial usage. Antimicrobials don’t breakdown fully in the environment. They can be found in animal waste which is then used as fertiliser or even fish and animal feed, often in other locations.

Antimicrobials in that waste remain active and could stress other microbes in the new area into developing resistance. Eating animal products containing high levels of antimicrobials or resistant infections could also allow AMR to develop and spread into people ,according to research from the World Health Organization.

Just like the climate crisis, AMR impacts upon humans, animals, and the environment. It’s a ‘One Health’ problem requiring action across many different sectors.

Antimicrobial resistance is a ‘One Health’ problem, affecting many parts of life with many routes of transmission

Antimicrobial resistance is a ‘One Health’ problem, affecting many parts of life with many routes of transmission

Why aren’t we acting already?

Well, certain communities are. Scientists are desperately working to develop new antimicrobial compounds, both in the lab and by testing natural products such as soil microbes and chemicals in plants. But even if we can make new drugs, AMR will still occur. It is, after all, a natural process. Resistance to new antimicrobial compounds will always evolve. But it will happen much quicker if we don’t bring our own use of antimicrobials under control.

What can community engagement do?

How can this highly scientific problem be communicated to the masses? How can people be motivated to take action? Just a few decades ago, the same questions were being asked around the challenge of climate change. We now realise that locally specific community engagement approaches can transform the way communities relate to the climate crisis. And we’re beginning to see lasting positive changes.

Community Engagement can be a tricky term to explain. Over the past three years, the CE4AMR network including myself, Dr King, Professor Cooke and our international collaborators have worked hard to define and specify exactly what we understand Community Engagement to mean in our research.

We see Community Engagement to be a process of creating equitable partnerships with multiple stakeholders to explore specific challenges from their perspective and support the development of locally meaningful solutions to these challenges. I know it’s not a short or snappy description! But the complexities and wording are important. Community engagement – or CE – hinges on the idea that there are multiple knowledges in the world. By better understanding these knowledges in relation to a specific problem, we can ask appropriate questions; we can then address that problem in a way that is meaningful and appropriate to a given community.

Creative processes allow people to use their local knowledge to suggest alternative behaviours.

CE encompasses lots of different methods that allow communities to share their knowledge and experiences. Within the climate crisis, informal approaches based in schools have been very successful. Young people feel respected and listened to. They share their own experiences and develop meaningful, appropriate changes to their behaviour to tackle the problem in question. They then carry these changes into their families and wider communities.

Other approaches bring new information to communities, for example explaining global warming, but then allow the community space to reflect on these problems through the process of creating films, music, drama, and stories. These creative processes can allow people to consider why a certain problem may be occurring in their own context and to use their local knowledge to suggest alternative behaviours.

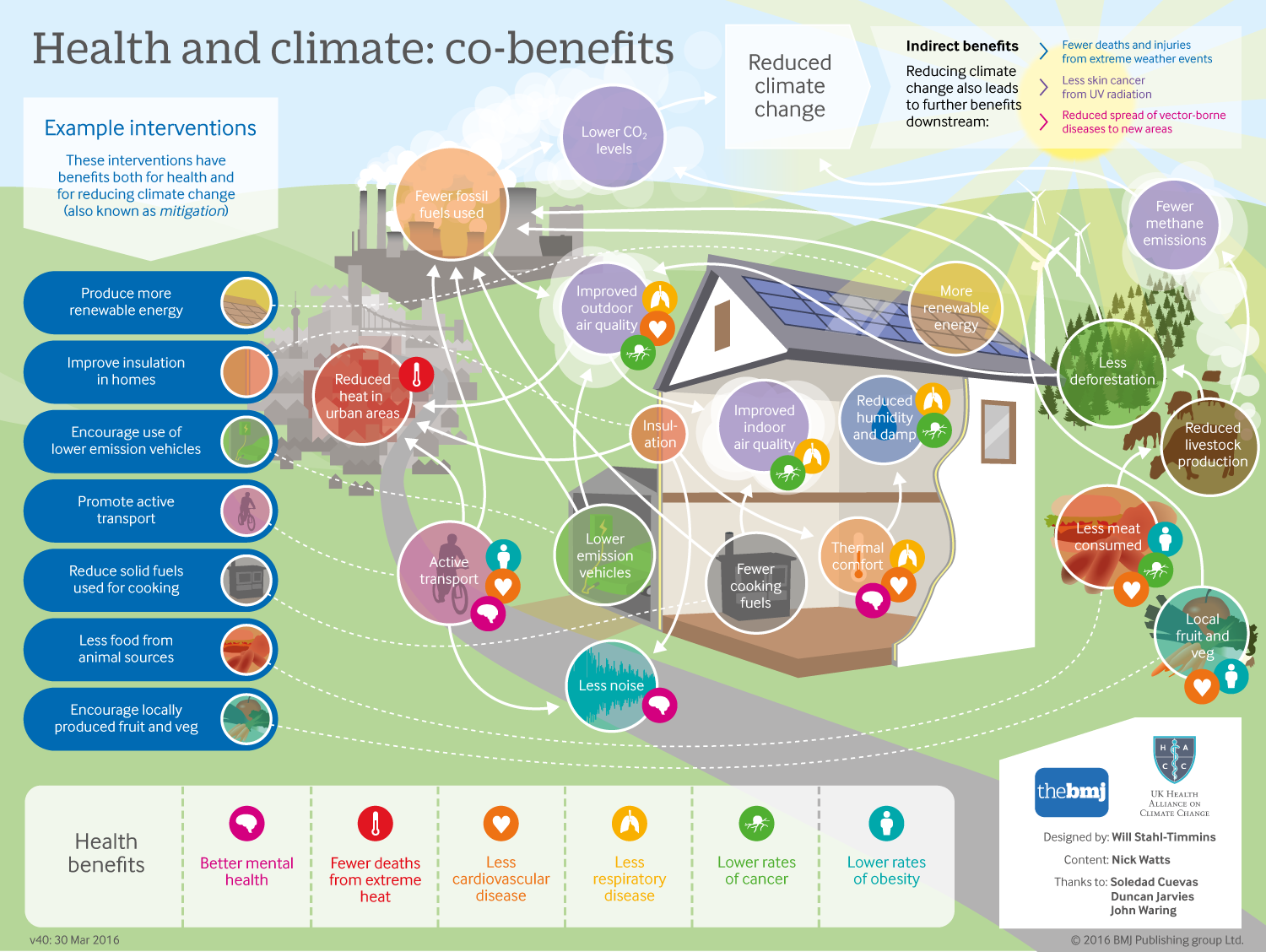

Talking about other benefits, like health, can persuade us to change our behaviour to protect against climate change.

Talking about other benefits, like health, can persuade us to change our behaviour to protect against climate change.

Immediate individual needs can often be at odds with long-term collective interests. Everyone in a community needs to reduce their use of cooking fuels to see an impact on global warming, yet everyone also needs to put food on their table.

Engaging people with these problems can be very challenging: it’s hard to imagine the benefits of changing what you do if they occur at global level, or very far into the future. Community engagement approaches can be helpful here. CE allows communities to put the climate crisis in the context of their own lives and suggest meaningful changes that can improve these.

For example, in sub-Saharan Africa stoves are essential household items. Women use them to boil water for drinking and cleaning, and to cook nutritious food like rice and yams. But most stoves use fossil fuels such as kerosene. CE activities, including information sessions and short films, have been very successful in encouraging women to switch to ‘clean-cook’ stoves.

These produce less harmful emissions, and so are better for the environment. And crucially, clean-cook stoves lead to less respiratory illness in young babies and children. This was very appealing to women: one of their main concerns is the health of their children and grandchildren. Clean-cook stoves allow them to boil water and cook warm healthy food for their families and protect their children’s lungs.

The challenge of AMR

The challenge of AMR poses similar social dilemmas. People’s actions are motivated by their immediate needs. For example, across many low and middle-income countries, people sell non-prescription antimicrobials as a way to make a living.

This behaviour is known to drive AMR and so it will eventually render the antimicrobial, their source of income, useless. But, even when they understand this, they may have no choice but to continue to sell drugs if they are to feed their families that week. Any efforts to change their behaviour must take this into account.

The climate crisis and AMR have some striking similarities and overlaps.

First the climate crisis itself can impact on AMR: changing conditions place microbes under stress. Clearly human behaviours which contribute to the climate crisis, such as burning fossil fuels, could also indirectly lead to AMR. Explaining this at community level is complicated and may take some time, but it is likely to be worthwhile.

Second, both hinge on responsible and equitable use of resources. Across the globe, some communities have very limited access to antimicrobials; in others you can pick up a couple of antibiotics at a teashop without a prescription or even a chat with a doctor. These examples mirror the global inequalities we see in access to energy and other resources. The climate crisis has brought these to light, and the same is happening, though at a much slower rate, for AMR.

Third, we need to consider the sustainability of our food. We know that our replacement of natural habitat with farmed land has severe consequences for our climate.

We also need to consider a habitat’s worth in terms of the microbes it contains. Changing a habitat often forces microbes to go somewhere else: livestock in newly cleared farmland are very vulnerable to infection from microbes which usually infect wild animals in that area. Treating that livestock can in turn bring antimicrobials into our food. Furthermore, reducing meat consumption is one of the best ways of reducing land lost to farming and the associated to risks to AMR and the environment.

However, some communities would struggle to find alternative sources of protein. Any such initiatives would need to be locally specific. Community engagement which can explain and help people think about these complicated challenges of AMR, habitat loss and food production could be very helpful.

How can community engagement tackle AMR?

Unfortunately, CE is not yet routinely used in AMR research. But some innovative projects are paving the way.

The University of Leeds’s CE4AMR network acts as a platform for existing community engagement projects addressing AMR across the world. The network is part of the University’s commitment to placing itself at the heart of a global community and to tackle global challenges.

One example of this is the Tackling AMR in Schools project I currently lead in Nepal. This is bringing together local school teachers, students and community members to co-design an educational resource on AMR. This project builds upon both the success of climate change education and on a previous piece of work by the CE4AMR network. In the CARAN project (Community Arts Against Antibiotic Resistance in Nepal), community members created their own short films based on local experiences of challenges around AMR.

These included using non-prescription drugs because they were cheaper, or failing to finish a full course of prescribed medication because it seemed sensible to save some for future illnesses. These films have already been shown to local government officials who used the information to draw up more locally meaningful policies on AMR.

They are now being used as a catalyst for conversations on AMR in education. And the original community members are gaining valuable skills in public speaking as they present their films and ideas to school teachers and students.

What will happen when antimicrobial drugs don’t work?

Quite frankly, I would rather not find out. Furthermore, by using community engagement approaches and learnings from community action on the climate crisis, I believe we won’t have to find out.

Listening to and engaging with the different knowledges embedded in communities have proven very effective in tackling local issues linked to the climate crisis. I hope my research at Leeds can have similar impacts in terms of AMR. This work needs to occur at community level, where specific challenges and solutions can be unpacked. But it also needs to be scaled regionally, nationally, and globally. Like the climate crisis, AMR is everybody’s problem but for very different reasons. Through CE we can respect these differences and understand that solutions and impacts will look different in different contexts.

Community engagement interventions around the climate crisis already take this more holistic approach. This is one reason they make a good model for tackling AMR. The World Health Organization has asked all countries to prepare a national action plan to tackle their AMR priorities. CE activities, such as the Nepalese project I’ve mentioned, could offer a way for marginalised communities to share their opinions and experiences to shape national plans and AMR guidance.

This is the kind of research activity that the new Leeds University strategy is looking to foster. One that harnesses its expertise in research and education to help shape a better future for humanity, working through collaboration to tackle inequalities and drive change for a better society.

But learning from the network suggests that the bulk of CE for AMR research focuses on addressing human antimicrobial use and minimising the human impacts of AMR. This is a valuable start. But we must also consider the One Health (human, animal, environmental) dynamics of AMR and recognise that these are intrinsically linked.

Across all the examples I’ve described, the striking similarity is that both the climate crisis and AMR are underpinned by human behaviour and the complicated social factors which influence it. There is no easy way of addressing why humans misuse resources, including antimicrobials. We know it’s not simply a lack of knowledge. Rather it is that conflicting social, financial, cultural and local challenges impact on our ability to engage with the world around us, and often lead us to making poor decisions.

What we can do is begin to understand the process around this decision-making and why poor decisions are sometimes made. People are much more likely to change their behaviour if they understand the direct personal consequences. Community engagement approaches allow us to do this in a way that is fair to everyone involved. And with antimicrobial resistance, that’s all of us.