Digital transformation begins with people

How do we become digitally literate?

Digital transformation is at the heart of the University of Leeds’ vision for the next ten years. This transformation will enhance students’ learning and enrich research activity, as well as improve the University’s own institutional operations. Leeds’ ambition is to use digital technologies and approaches to fulfil its desire to be a university that makes a difference. However, digital transformation begins not with technology but with people, Leah Henrickson argues. She explains what makes us ‘digitally literate’ and how digital literacy helps us get the most from the digital in our lives.

Hello there, reader. Thanks for joining me here. Whether or not we’ve met before, you probably feel pretty confident that I am a person, like you. And, just like you, I have my own opinions, knowledge and stories to tell.

As I write this, I’m presuming certain things about you: that you can read these words, that you want to read these words, and that you’ve come to these words with certain expectations that are informed by your past reading experiences.

Even though we’re not together physically, you and I have already established a relationship through our mutual use of media. In the case of this online essay, these media are textual and digital.

We’ve long lived in a media-saturated society, but the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified our use of digital media, drastically changing how we connect with each other. Under government instructions to keep physically distant, we’ve become dependent on digital media for most – if not all – of our communications. Through emails, video calls, online games, social networking sites, and more, we share our information, time, and cat videos.

But such dependency on digital media often assumes that we are all ‘digitally literate’: that is, that we all have the skills to use digital tools confidently. This assumption creates and reinforces unequal levels of access to digital media, as well as unequal senses of belonging in digital spaces.

In its new strategy for 2020–30, the University of Leeds has committed to a ‘digital transformation’ to make the most of its activities across education, research and innovation. Leeds wants to establish a strong digital presence that supports the local, national and international communities it serves. Its ambition is to foster a culture of collaboration that contributes to social good.

However, we can’t achieve community, culture or impact using digital media without first ensuring sufficient digital literacy across our various stakeholder groups.

For the University’s digital transformation to be effective, we need high and sustained levels of digital literacy among staff, students and institutional partners alike.

But where do we even start?

We start with ourselves. With prudent use of digital media, we can facilitate self-awareness, mutual understanding and senses of belonging. We can use these media to express ourselves in ways that we couldn’t have imagined just a few years ago.

These media offer us new playful, professional and practical avenues for exploring the world and our places in it. They also offer us lots of new choices about how we communicate. We’re no longer bound to text and image – we can easily use combinations of text, image, video, sound, and other elements to say what we want to say.

I’ve always been interested in the ways we communicate with each other. When I was young, I used to love going to my local bookstore and flipping through pages upon pages of stories: stories transported from authors’ minds to my own through print.

As I got older, this love led to degrees in Media Studies and Book History. Isn’t it amazing how we can use media like books to learn from each other across space and time? All we need is the ability to read the same language.

For so long, the physical book has been a primary form of communication, and it still is. But digital developments add new layers of communicative possibility that I’m especially excited about.

Unlike with books, though, we need more than just the ability to read the same language as others in our digital networks. There are hardware and software requirements. Then, once we’re connected, we need to understand the messages we’re receiving.

These messages might go beyond language. They may require us to interpret non-textual formats like GIFs or extratextual formats like memes. They also require us to figure out what’s true and what’s not, and to make sense of messaging presented alongside huge amounts of other content.

My current work at Leeds looks at how we can use digital media to improve our understanding of ourselves and others, particularly through digital storytelling.

Along with my colleagues in the School of Media and Communication, I’m thinking about how we can promote digital literacy to boost such understanding. How might we use this understanding to reduce inequalities in digital spaces? How might we build upon digital literacy to develop and maintain inclusive communities? These questions must also inform our strategy for digital transformation at the University of Leeds.

What is digital literacy?

On its website, the UK’s National Literacy Trust defines literacy as ‘the ability to read, write, speak and listen in a way that lets us communicate effectively and make sense of the world’.

People with low literacy might not be able to read books or newspapers, understand signs and labels, fill out forms, or follow written instructions. The emphasis here is on what we call functional literacy: the ability to comprehend and produce text to participate in everyday life.

In digital spaces, functional literacy refers to our ability to comprehend and produce digital material for everyday participation. Of course, digital material comes in many forms. What functional literacy looks like will vary, depending on what each person needs to do to be able live, socialise and learn comfortably.

Literacy isn’t only functional, though; it also extends to more abstract critical thinking. Critical literacy means that we can question the content we consume, curate and create. Through such questioning, we might think about why content was created, by whom, and how that content creates or reinforces social power structures.

So, literacy isn’t just something we do; it influences how our brains work and how we approach self-reflection and our social roles. The cognitive and social effects of textual literacy are well documented, but we’re only just beginning to understand the precise effects of digital literacy.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that digital media require new kinds of literacies: ones that take into account the heightened globalisation and access to diverse perspectives afforded by the Internet, and that recognise the symbolic, persuasive and emotional dimensions of digital media – both online and offline.

Digital literacy ultimately centres on what is most important: the people, not the technology.

Digital literacy ultimately centres on what is most important: the people, not the technology.

Popular definitions of digital literacy tend to separate digital media from their users. We access, understand, and evaluate content using these media; these media are things we use, not are.

But digital literacy is about more than knowing how to flick a device’s on and off switch and use email. It’s also about internalised new habits and expectations – even new senses of self.

Have you ever quickly Googled the answer to a question mid-conversation? Visited a new online shop, but still known exactly what buttons to press to make a purchase? Worn a certain shirt because it’ll look good in the photos you know your friends will take when you meet up? You’re showing your internalised digital literacy by altering your behaviour so as to use digital media more effectively. You might not even realise that you’ve done this, developing your digital literacy through unconscious trial and error.

At Leeds, we want to make the unconscious conscious to ensure that digital literacies sufficiently serve individuals and communities – now, and in the future.

To be fully digitally literate, we must consciously reflect on our own experiences of digital media and how they might affect our relationships with other people. We must think about how digital media are used, by whom, and why. These media don’t exist in isolation, and they’re certainly not neutral. They are, after all, extensions of human intention.

Really, we don’t just use digital media – we are those media. So, it’s vital that every discussion of digital literacy ultimately centres on what is most important: the people, not the technology.

A digital university

Those of us working in universities – teaching testable content, but also helping students hone their social skills – must think deeply about who we are and what we are doing when trying to foster our students’ digital literacy.

We must also think deeply about who our students are, and how we might meet everyone’s communicative needs through compassion and collaboration. We must account for our own preferences, and sometimes put those preferences aside to support others’ communicative needs.

Sure, we want to teach our students how to communicate according to industry standards, but these students also have a thing or two to teach us about how to use digital media. The world is constantly changing, and our digital literacies need to constantly change with it.

The University of Leeds’ vision for its digital transformation hinges on effective, creative, innovative and research-informed use of digital technologies, data and approaches. The transformation’s aims include enhancing institutional operations, supporting collaboration and growing the University’s online educational portfolio.

These are all commendable aims with significant potential for solidifying the University as a champion of both local and global advancement. To meet these aims, though, the University needs to think carefully about how it’ll balance an authoritative digital presence with a willingness to adjust that presence as needed.

The good news is that there are no objectively right or wrong ways to use digital media. The ‘right’ ways are simply those that help us most effectively share our messages with those we’d like to share them with.

We can try new things to see what works and what doesn’t, adjusting our practices in light of new digital options when they’re available. We just can’t get too comfortable. Like our operating systems, our digital literacies need constant updating.

Once the University feels confident in its own digital literacy, it can work towards encouraging digital literacy in others. This isn’t just about teaching people how to use computers; in itself, being functionally literate in computer use doesn’t guarantee full digital literacy or empowerment.

We need to work with individuals to determine what forms of digital communication best suit them. We also need to find what helps them form meaningful connections with other people and the world more generally.

Collaborations in digital spaces can support the formation of these connections. For example, some of my colleagues at Leeds have worked with local people and cultural institutions to create virtual archives together. These projects have affirmed senses of belonging across various kinds of communities.

Online elements of these projects have also broadened communities by facilitating global access to places and groups that have historically felt hard to reach, whether for geographical, logistical or social reasons.

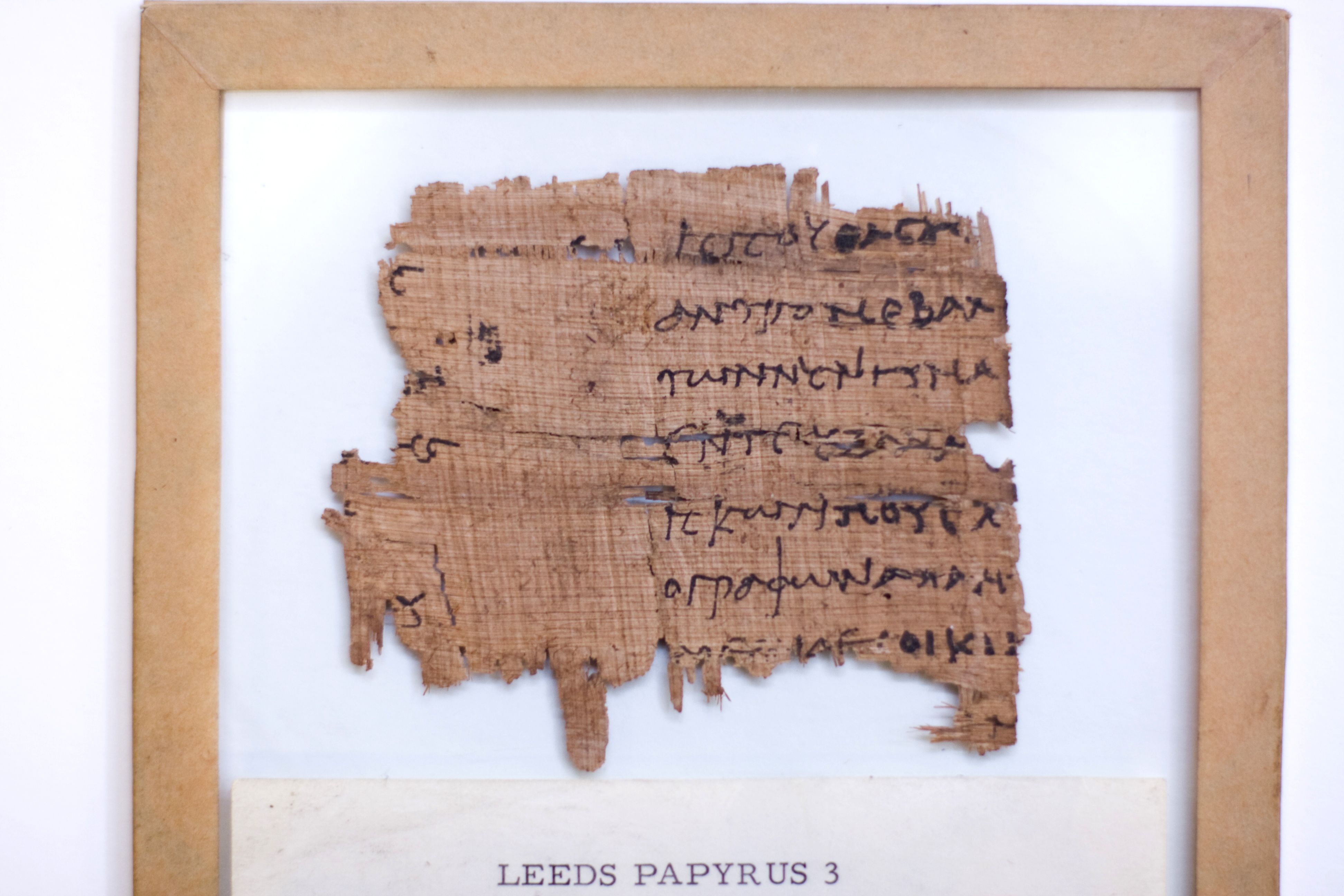

Treasures such as this papyrus from the University Library Special Collections are now readily available to access digitally. Credit: Leeds University Library Special Collections.

Treasures such as this papyrus from the University Library Special Collections are now readily available to access digitally. Credit: Leeds University Library Special Collections.

As just one example of this kind of collaboration, my colleague Tom Jackson constructed an immersive and participatory virtual archive of a Leeds arts centre. Including submissions from various people with ties to the centre made the archive a more thorough representation of experiences in that space. Reflecting on one artist’s contribution, Tom writes:

This act not only illustrated how engaged she was in the co-creation of the archival records related to her space, it also revealed a significant change in the balance of power. By indexing my presence within the virtual archive through the creation of her own materials, I was no longer the ‘author’ and she was no longer the ‘subject’. We were both implicated in the authorial processes and present within the resulting archival records.

Joanne Armitage, another one of my colleagues, has investigated how we might encourage self-expression through digital media.

She’s focused on Algorave, a process of using algorithms (‘algo’) to generate dance (‘rave’) music. Joanne is an Algorave artist herself. By teaching other women how to make computer-generated music, she’s overcoming perceptions of coding as a masculine activity. She’s introducing people to new forms of music-based communication that are uniquely digital. But, by providing women with opportunities to develop their coding skills, she’s also pushing back against gendered inequalities in digital spaces.

We don’t all speak the same digital languages. And, even when we do, we don’t all use language the same way. So, when we encourage others to communicate though digital media, we must be flexible in accommodating different – and even totally unexpected – forms of expression.

Otherwise, we run the risk of establishing new social inequalities rooted in our own views of what is and is not ‘acceptable’ in digital spaces.

Communicating online with sign language.

Communicating online with sign language.

Practice-based research, like that of Tom and Joanne, explores how we can speak through digital media. On the flip side, theory-based research teaches us how to listen. Such research is well underway across the University of Leeds.

Helen Thornham has written extensively about digital infrastructures that promote capitalist neoliberal and gendered cultures: cultures that amplify some voices and silence others. Nancy Thumim has considered how we amplify and silence parts of ourselves online. Christopher Birchall has explored issues of identity and agency in online political discussions. Holly Steel has analysed the role of the Internet in curating and communicating news about war and conflict. Tom Tyler has looked at how representations of animals in videogames make us think about vitality, vulnerability and what it means to be human. (See ‘About the projects’ to follow up on all this research.)

The work of all of these researchers – and many more – encourages us to think about who is speaking, to whom, how, and why.

As we move forward with the University’s digital transformation, we of course need to speak, sharing our knowledge across our stakeholder groups. But it’s just as important that we listen: to ourselves, to each other, to the world.

Supporting digital transformation

It’s easy to forget that every piece of digital data actually stems from a person with a unique perspective and lived experience.

To be sure, digital literacy is a fundamentally social concept, because our shared literacies allow us to connect using languages that we have, at least in part, in common. However, experiences of digital media are hardly uniform.

Here, I’ve affirmed the value of individualised focus for digital literacy, but I’ve also stressed the need to think more globally about facilitating interpersonal communication and understanding through digital media.

How University of Leeds research is making new knowledge accessible across the world.

Transcript: University of Leeds Strategy 2020-2030: Digital transformation (opens in a new window)

The University of Leeds wants to undergo a digital transformation as an institution, with a vision and strategy shared by all those involved. But what precisely are we transforming from and into?

It isn’t enough to give people access to computers, tablets or mobile phones and call it a day. Mere access to digital media isn’t empowerment.

Similarly, putting information online doesn’t mean that people will be able or want to use it. For example, making research freely available online – ‘open access’ – is a nice idea, but that information needs to be presented in a way that’s understandable and useful to the general public.

Plus, there’s a lot of incorrect – or worse, harmful – content online: just because something is digital doesn’t mean it’s good.

Leeds is striving towards more open access material, making this content accessible via Internet exhibitions, massive open online courses (MOOCs) and other digital formats. By curating content in a variety of ways, the University is meeting people where they are, and helping them get to where they want to be.

We need to remember, though, that technological solutions aren’t always the most appropriate answers to questions about education, research and innovation. As our time under COVID-19 restrictions has shown, digital alternatives cannot and should not wholly replace in-person experiences.

As useful as a MOOC may be for complementary and lifelong learning, for example, students and staff both benefit from sharing physical spaces that allow us to read one another’s body language and engage in immediate dialogue. Likewise, while online systems are useful for tracking student progress, the analytical data held in these systems only tell part of a student’s story.

We need to think about how we can use these data to capture and enhance student experience. But we must not overlook the fact that we’re talking about actual people here – people who can’t be reduced to numbers. If a plan for digital education, research or innovation doesn’t explicitly address these kinds of limitations or potential negative social consequences, then that plan is incomplete.

As our time under COVID-19 restrictions has shown, digital alternatives cannot and should not wholly replace in-person experiences.

As our time under COVID-19 restrictions has shown, digital alternatives cannot and should not wholly replace in-person experiences.

This means that measuring the success of a digital transformation might be extremely difficult.

Digital technologies all depend on coded instructions that don’t account for anything outside of what’s instructed. However, humans don’t always do what you expect them to do. They don’t always follow the rules.

For this reason, digital literacy also means being able to determine when digital technologies aren’t the best choice. Even when they are, we need staff who can manage and adjust systems in response to new social situations, and who can teach stakeholders how to use these systems with a critical eye.

Maybe all of these adjustments will mean that we won’t be able to decide on numerical measures of success for some of our digital transformation, and that’s okay. Computers might be great at crunching numbers, but people are more than quantifiable. Maybe we should be assessing things like quality of experience, social satisfaction and self-confidence instead.

We can communicate with other people more effectively if we develop digital literacies that are both functional and critical, and that reflect our diversity of perspectives and experiences. But we continue to exist in a world bigger than the digital: a world that is beautiful; a world that is troubled; a world that is so awesomely complex.

Meaningful digital transformation can only happen when we find ways of using digital media that contribute to greater appreciation of our world and everyone in it.

The University of Leeds’ Digital Literacy Framework offers a useful starting point for those looking to further develop their digital literacy. However, as this framework implies, the basis for any meaningful digital literacy or transformation is not technology. It is not hardware, nor software, nor platforms, nor networks. It is people.

I’ve insisted here that we can’t become fully digitally literate – as individuals or an institution – until we explicitly reflect on ourselves and our community. Our digital transformation must begin with people, it must end with people, and it must include people every step of the way.