Circular economy

Coming together for a sustainable, fairer and low-carbon economy

Unsustainable patterns of production and consumption are driving global challenges such as biodiversity loss, climate change and growing inequalities. Humanity extracts natural resources at an ever-increasing rate and adopts wasteful lifestyles polluting the land and the seas. Livelihoods are destroyed in exchange for a single moment of convenience. But there is an alternative – and it’s one that we can all get involved in. Anne Velenturf and Michael Howroyd introduce how a circular economy can help.

Coffee on the go. New outfit for every occasion. An ever fancier phone. Plastic bags galore. Live faster. Dream bigger. Feel better?

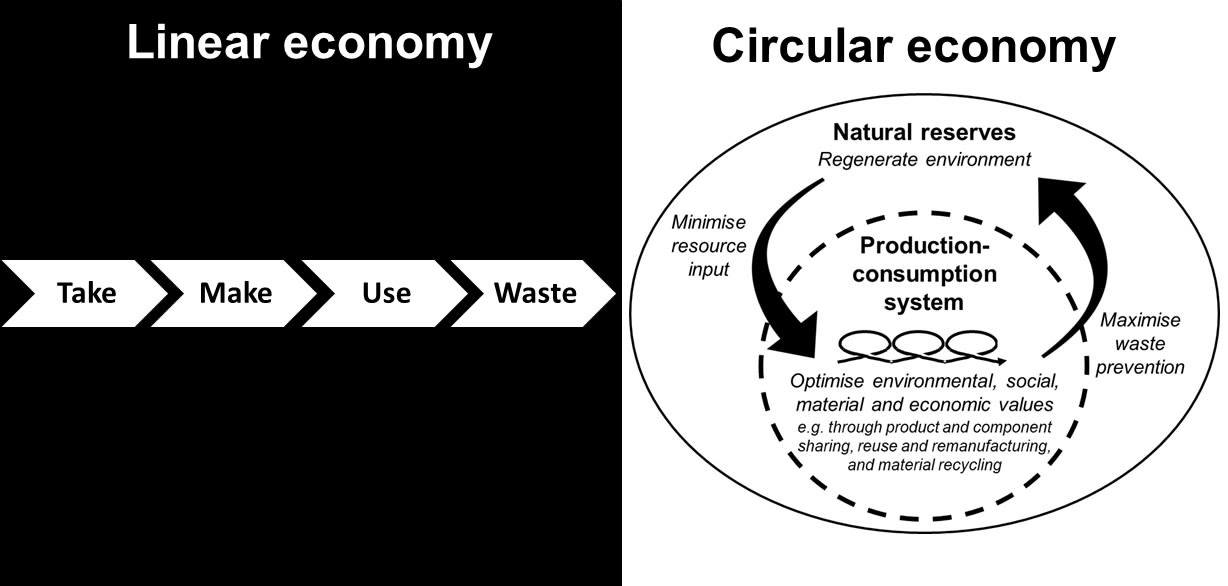

This is the linear economy. We take, make, use and dispose of resources as if there is no tomorrow. It’s the disease of the twentieth century, planted in the 1930s as a medicine against the Great Depression, when the US introduced ‘designed obsolescence’ to accelerate consumption. This wasteful model then spread across the globe following the Second World War.

The UK government’s current economic recovery plans still bang the drum of this archaic mantra, with a forcefulness that suggests there is no better alternative. But there is: a circular economy, aiming to make better use of materials and products. A circular economy designs products to last – products which are fit for reuse, easy to repair and, eventually, recycle.

How a circular economy differs from a linear economy. Credit: author generated. Attribution: ShareAlike 4.0 International.

How a circular economy differs from a linear economy. (Credit: author generated, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International.)

Working at the University of Leeds, we are keen to collaborate with our communities to make a positive and practical difference. We’re both passionate about people and environment.

Having a combined experience in sustainability for nearly 50 years, we’ve witnessed how policies come and go, how goalposts keep moving, and how evidence is used to make a positive start but generally such initiatives do not stick around long enough to enable structural change. With the Yorkshire Circular Lab, we have created a platform for open and continuous collaboration so that we can build on previous experiences and accelerate sustainable change.

Sitting within the Yorkshire and Humber region of England, the University of Leeds is a global leader in research, teaching and knowledge exchange for a sustainable circular economy. Our work on this is part of the University’s ambition to make a real difference, across all sectors, and from the local to the global scale.

Connecting the local to the global

World-famous for its natural beauty – from dramatic coastlines to rolling hills and colourful moors – Yorkshire and the Humber stretches from the Pennines to the East Coast of England. That natural diversity is reflected in our industrial heritage.

Valuable natural resources – such as fresh water, fertile land and seas, coal and iron – put the region at the forefront of industrialisation. The Yorkshire coalfield helped power heavy industries such as steel, cement and glass. Flocks of sheep grazing on the lush hinterlands fuelled woollen mills and the textiles industry.

Agriculture remains one of its biggest industries, as does food processing, which now also offers foundations for innovative biochemical industries. The area around the Humber hosts the busiest port complex in the UK. Where fishing once dominated, offshore wind is increasingly offering new opportunities. Environmental technologies, digital industries and financial services are among the growth sectors in the region.

Scenic countryside, market towns and cities – Yorkshire and the Humber is incredibly diverse. Its rich cultural and natural history make it a much-loved tourist destination. Of course, it’s also home to about 5.5 million people, similar to the population of Scotland.

But not all is well in ‘God’s own country’. The effects of climate change are increasingly visible, with warmer summers and wetter winters. Flooding and severe coastal erosion have become part of the normal fabric of life.

According to the UK’s clean air strategy, industry, traffic and domestic heating cause dangerous levels of air pollution, with most of Yorkshire and the Humber under a blanket of pollution, and some urban areas having the worst air quality in the UK outside of London. Fly tipping of waste blights the landscape at an enormous cost to landowners.

Levels of deprivation are relatively high (see The English Indices of Deprivation 2019), especially in urbanised areas like those within and around Hull, Leeds, Middlesbrough, Bradford and Sheffield. Health and life expectancy are below national average, as are levels of employment and income.

And across the UK, social stresses are mounting. We’re living increasingly isolated lives – even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Levels of loneliness are starkly on the rise. Social company often comes through TV and social media, and this exposes us to marketing that persuades us to buy our way to happiness.

Levels of debt are high. Before the pandemic, 64–71 per cent of 18–44 year olds in the UK had some form of consumer debt (not counting any mortgage), such as a credit card bill.

Young people, in particular, are concerned about the future, and many are suffering from climate anxiety as the climate emergency intensifies.

A complex global web of problems

The local and national problems we see in Yorkshire and the Humber are part of a wider network of global sustainability challenges.

The extraction of resources from the natural environment and the manufacture and transport of products are energy intensive: this drives greenhouse gas emissions and causes air and water pollution. These processes also occupy space that would otherwise be available for nature and biodiversity.

In turn, this reduces nature’s capacity to maintain a steady environment, one where we can live safely. We can see this, for example, in the increasing heat waves, droughts and wildfires around the world, as well as extreme weather events and flooding. It has been suggested that pandemics might become more common, due to pathogens associated with environmental decline.

Research has found that there are more materials in our society than in nature: measured by weight, there is now twice as much plastic in the world as there are wild animals, and there are more buildings and built infrastructure than there are trees and shrubs.

Circle Economy estimated that, in total, humanity consumes 100 billion tonnes of resources per year. Unless we change our habits, this number is forecast to rise to 180 billion tonnes per year by 2050. Many of these resources are used only for a short time, then go to waste in incinerators and landfills where they often continue to cause pollution.

Such overexploitation of natural resources is driven by economic models focused on short-term gains to acquire wealth for a limited number of people. It’s a political-economic model designed to drive inequality.

Such inequality, it’s argued, creates competition and a willingness to be more productive. However, the result is social deprivation in many parts of the world, adding pressure to living conditions already made precarious by environmental disasters.

Social inequalities are systemic: unless the current overriding economic model changes, most people may never get a fair opportunity to climb out of poverty. The neoliberal economic model has left us vulnerable to economic shocks and exacerbates a loss in social cohesion.

How circular economy can help

The wasteful use of resources – in which we take materials from the environment, make something, use it for a short spell, then throw it away – is at the root of sustainability challenges. Circular economy makes better use of both materials and products (see Principles for a sustainable circular economy at ScienceDirect).

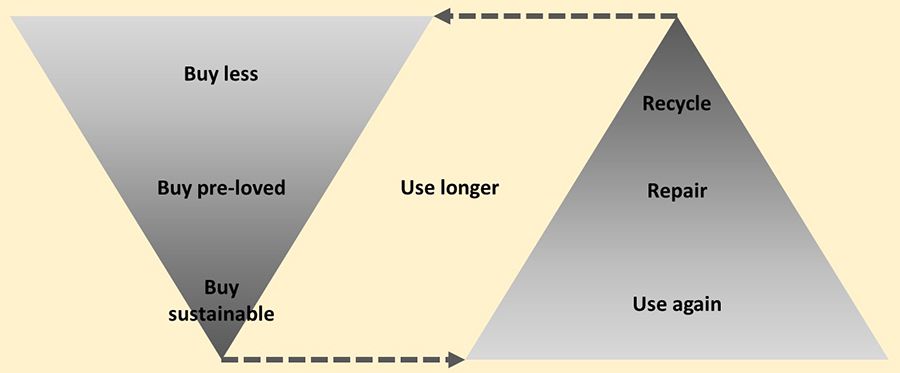

We can think about this under four headings: using less, keeping products in use for longer, recycling waste, and safely returning materials to the environment.

Everyone can start adopting more circular economy behaviours. But what makes the most suitable changes to your life does depend on your current lifestyle. Wealthier households tend to consume more and, as a consequence, generate more waste.

In such cases, buying less and – when you do need something – buying second-hand can substantially reduce your environmental impact. Reusing and repairing products is another important way to limit consumption and waste. And joining a clothes-swapping party or a repair café can also be fun!

Changing behaviours can be difficult though. There can still be social pressure to buy new outfits and gadgets, for example. And sustainable choices simply may not be available to you.

Recent research showed that circular economy practices for housing, food and transport offer the biggest potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and a very good chance to avert catastrophic climate change.

Measures at this level could include more energy-efficient homes built with reused and recycled construction materials, eating a healthier diet containing fewer animal products, and more of us supported to work more from home to reduce travel, or to share a vehicle if we do need to commute.

Circular economy practices can significantly contribute to sustainability. Circular economy is essential for climate action. Analyses by Circle Economy have demonstrated that the total of national commitments from all countries for climate change would reduce global greenhouse gas emissions associated with resource use from 60bn to 56bn tonnes in 2030, putting us on a trajectory of 2–3⁰C global warming.

Additional circular strategies, however, would bring emissions down to 33.2bn and put us on a pathway to net zero by 2044. Moreover, circular economy can create new business opportunities, such as repairs and servicing, supporting over half a million jobs in the UK alone by 2030.

Circular economy involves reduced resource use which can be implemented by buying less, second-hand and sustainably produced materials and products, that are used for longer and reused and repaired where possible before being recycled. Credit: author generated. Attribution: ShareAlike 4.0 International.

Circular economy involves reduced resource use which can be implemented by buying less, second-hand and sustainably produced materials and products, that are used for longer and reused and repaired where possible before being recycled. Credit: author generated. Attribution: ShareAlike 4.0 International.

Stepping up in ambition

Circular economy has the potential both to bring economic benefits and reduce impacts on climate and environment.

In the past ten years the concept has rapidly gained momentum within governments and businesses, comfortably slipping into existing economic models with a promise that ‘decoupling’ resource use from economic growth will solve our biggest challenges by allowing economies to grow without corresponding increases in pressure on the environment.

The latest evidence from the European Environmental Bureau, however, suggests that there hasn’t been enough progress on decoupling – and it’s unlikely that there ever will be.

It’s not the end of the circular economy dream, but we must raise our ambitions. We must aim not to reform but to transform our society. In the Global North, we need to halve average consumption of resources per person to stay within safe environmental limits, for example shifting from resource consumption to more experience, sharing and service-based models. The Global South has the opportunity to leapfrog towards a more sustainable model of production and consumption straight away.

A sustainable, transformative circular economy requires a deep rethink about what we need as human beings to live a good life – and to leave the planet in a better state for future generations.

The purpose of a sustainable circular economy changes from short-term economic gains, to organising fair access to resources enabling people to have a good life within environmental limits. It will require far-reaching changes to political-economic models, to the infrastructures through which products are designed, manufactured and brought to consumers, and to the lifestyles of billions of people. But solutions are already out there.

The difference between a recycling “circular” economy and sustainable circularity.

The difference between a recycling “circular” economy and sustainable circularity.

Yorkshire universities are researching solutions

Research at universities across Yorkshire is already supporting the development of a sustainable circular economy, linking big and radical ideas to practical implementation from global to local scales. This research draws from a thorough understanding of energy and resource patterns throughout the lifecycle of materials and products.

Projects are modelling flows from extraction and manufacturing through to retail, consumption, and solid waste and wastewater. Scientists are developing smart tools and approaches to analyse resources data, so that we can understand the sustainability implications of potential solutions.

Solutions are being developed for healthy and steady food supplies, sustainable construction, and the management of wastes – including from food, electronics, textiles, plastics and construction. Innovative technologies will better segregate, disassemble and recycle waste, turning waste products into valuable resources.

Such solutions can also help to clean up our environment, recovering metals and minerals from legacy landfills created from our industrial heritage.

Circular economy solutions can only work if they are more economically viable than our old wasteful ways – and if they are sufficiently in demand. This means that ‘linear’ practices – such as selling as much stuff as possible for the highest profits – must count the true cost of production to the environment and communities. This true cost will make linear products more expensive and, conversely, ‘circular’ ones more attractive.

We’d also like to see products with a high impact banned from our markets, for example electronics that can’t be repaired or products for which there is no sustainable waste management solution available in the UK, such as certain plastics.

But such measures affect prices, often hitting households with smaller incomes the hardest. Ensuring a just transition requires careful consideration and government involvement. Researchers are developing sustainable economic theories and business models to help solve such challenges.

No more ivory towers

As the COVID-19 pandemic has brought home, our actions impact on each other – across our communities and across the world.

Implementing a circular economy in a region like Yorkshire and the Humber requires harmonised action from people in local governments, business owners and managers, civic and voluntary organisations, citizens and researchers. For example, when households and businesses want to reuse more products and recycle more waste, local governments need to ensure that the right facilities and infrastructure are in place.

Circular economy solutions must be well-embedded within local contexts: what works in a city may not work so well in a rural village.

In cities food leftovers may fly out of the shop via a smart phone app, but not in a small village with less people and unreliable broadband. Converting phone booths into ‘libraries’ where local residents can borrow expensive tools might be a great success in villages; in cities with greater demand a more managed approach may be required.

Transitioning to a circular economy is also a matter of democracy. What kind of circular economy do citizens want? Do we want to collectively switch to a more plant-based diet? To begin sharing cars? To go chemicals free? To start building our homes with reused and recycled construction materials?

There are many steps to change for a circular economy, which we can take one at a time. Many require research to develop new technologies, support behaviour change, and investigate how new markets can be created and how policy can help.

Researchers depend on citizens, companies and governments to tell them which challenges are the priorities. Collaboration with our communities – from the start of research to developing solutions and embedding them locally – is essential to deliver a transition to a sustainable circular economy at speed.

People have choices. You have a right to be informed and educated – and you have the right to a voice in changes that will deeply impact on your lifestyle.

Universities can help to build bridges between citizens, civic and voluntary organisations, governmental bodies and companies, and the Yorkshire Circular Lab aims to support these organisations in the transition towards a circular economy in just this way.

The Leeds Repair Café at Leeds University Union: An opportunity to have broken items fixed, as well as share and learn useful repair skills. Photograph: Michael Howroyd.

The Leeds Repair Café at Leeds University Union: An opportunity to have broken items fixed, as well as share and learn useful repair skills. Photograph: Michael Howroyd.

Collaborating via the Yorkshire Circular Lab

The Yorkshire Circular Lab is a living lab that bundles together academic expertise on circular economy and joins up universities across Yorkshire, such as Hull and Huddersfield, with regional governments, businesses, civic sector organisations and communities.

It was initiated by academics from the University of Leeds and its Sustainability Service together with stakeholders outside of academia such as Kirklees Council and Hull City Council and the York and North Yorkshire and Leeds City Region Local Enterprise Partnerships.

It’s at the forefront of a general move at Leeds away from the concept of a competitive university environment, to one where universities collaborate with each other and with other institutions to bring about social good.

Plans for the Yorkshire Circular Lab were co-produced with stakeholders across the region. Together, we developed a partnership to deliver on five priority areas for action:

1. Develop a knowledge and tools hub to make scientific evidence accessible for practitioners, with examples, manuals and implementation tools for policy and business, and involving communities for behaviour change and skills development.

2. Bridge research and implementation with student education and research projects.

3. Build a community of circular economy stakeholders and offer continuity for collaborative implementation of a circular economy in Yorkshire.

4. Support circular economy implementation by partners outside universities, through dedicated projects, awareness raising and advice.

5. Monitor progress in circular economy practice and regularly evaluate demand for support, proactively covering gaps in circular economy capacity and avoiding duplication of efforts.

Five priorities were coproduced for the Yorkshire Circular Lab.

Five priorities were coproduced for the Yorkshire Circular Lab.

The Yorkshire Circular Lab also creates a real-world teaching environment for students, benefiting from the opportunity to learn and apply new knowledge to challenges raised by our partners outside of universities through internships, guest lectures and dissertation projects.

Circular economy applies to a broad range of subject areas, from environmental studies to engineering, social sciences and business administration. We anticipate that a strong growth in ‘circular jobs’ around the world will bring a higher demand for teaching in this versatile subject area.

Get involved

Research led by the University of Leeds has contributed to policy at global, national and regional scale. Leeds researchers have shown how much energy, water and materials we use as a society.

We coproduce global agreements such as climate agendas, shape national policies such as industrial and resources strategies, and facilitate regional collaboration to implement circular economy.

Coupled with the latest social insights, technological innovations and alternative economic theories, Leeds is unique in its capability to investigate how people can and would like to live well within a flourishing environment.

The concept of circular economy offers so much potential to take action together to solve the major environmental, social and economic challenges of our time. But it requires joined-up action to build up our knowledge as we make the big change towards a circular economy. Nobody holds all the answers, and we can only move forward through collaboration.

Learning how to repair a VHS cassette player at The Leeds Repair Café in Leeds University Union. Photograph: Michael Howroyd.

Learning how to repair a VHS cassette player at The Leeds Repair Café in Leeds University Union. Photograph: Michael Howroyd.

Everyone can start to implement a circular economy now. The momentum for circular economy is huge. Circular economy is positive. It’s fun to implement. It creates a good vibe in our community.

Whether it’s each of us trying to reduce what we buy, use more second-hand shops or recycle better at home, companies trialling new products and services that fit better within a circular economy, governments developing an amenable environment for a regional circular economy, or universities making circular economy expertise available to communities and students – we can all start doing something today.