Art School for Rebel Girls

Young women, feminism, art and collaboration in Leeds

What if girls were taken seriously as the producers of art, film and literature, rather than merely as subjects? Images of women shape attitudes and beliefs about women. Elspeth Mitchell and Gill Park wanted to put the power to make these images into the hands of girls.

They set up the Art School for Rebel Girls, working with the local community around the University of Leeds. Linking the feminist activism of the 1980s with how we live today, the Art School provides a space for girls to foster confidence, creativity and collaboration.

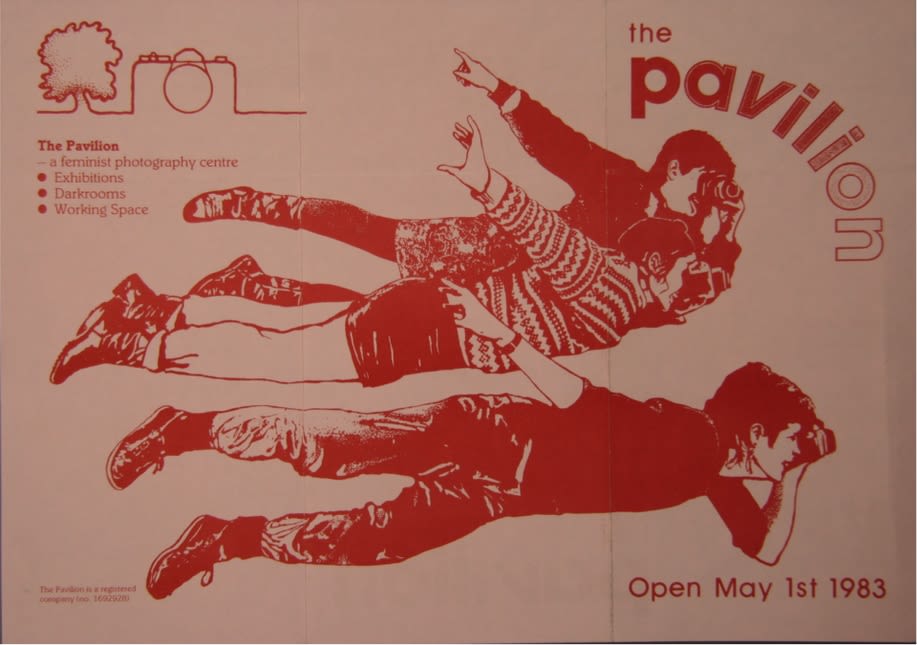

In May 1983, The Pavilion Women’s Photography Centre opened in a renovated refreshment pavilion on Woodhouse Moor, a public park located between the University of Leeds campus and the inner-city suburb of Hyde Park in North-West Leeds.

Like so much women’s history, the significance of The Pavilion’s founding moment was, until recently, all but forgotten. But it was a unique and path-breaking project – the first of its kind in the UK. Its archive is housed in the Feminist Archive North, within the University’s Special Collections. The current Pavilion team, led by Will Rose, is still commissioning contemporary art in Leeds.

Leaflet advertising the opening of the Pavilion Women’s Photography Centre. Image: Feminist Archive North and Pavilion

Leaflet advertising the opening of the Pavilion Women’s Photography Centre. Image: Feminist Archive North and Pavilion

In 2013, to mark its thirtieth anniversary, the team began an adventure in The Pavilion archive, inviting artists in to see what they could find. (Much of this work was led by Pavilion producer, Will Rose.) This sparked newly commissioned artwork and events responding to The Pavilion’s feminist beginnings.

At this time, Gill was director of Pavilion. She was so inspired by The Pavilion’s feminist history that she applied to investigate its artworks and exhibitions further through a PhD under the supervision of Professor Griselda Pollock, who had herself supported The Pavilion’s work during the 1980s. While studying in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at Leeds, she met Elspeth who was undertaking a PhD on ‘the Girl’ in contemporary art and film.

Talking together we were inspired by Pavilion’s early activist and educational work with young women. The stories resonated with the impact that art and feminism had on our own lives years later.

We wanted to understand what an arts education project could look like today if it sought to address the particularities of young women’s lived experience through methods of feminist art practice.

Learning from The Pavilion’s historic work, in 2017, we founded the Art School for Rebel Girls as a partnership between Pavilion and the University of Leeds.

The three-year creative programme was delivered by Elspeth, much of it in collaboration with Sarah Harvey Richardson, an arts researcher and pioneer of the Saturday Art Club at the University of Leeds. Talented University of Leeds students and alumni Bella Carreras, Carmen Okome and Alice Needham, and Pavilion producer Kerstin Doble, lent crucial support to the project.

We achieved funding for the project from Soroptomists Leeds, who were particularly interested in the project’s potential to help girls and young women maintain the aspirations they have as children through adolescence.

As researchers in our 30s, we’re mindful that we both came of age at the cusp of the internet revolution. We’ve had easy access to digital cameras and, later, smartphone technology and social media. Together these have changed the possibilities for women to both represent themselves and to present those representations to others.

Looking back at The Pavilion’s history, and coming to understand the political relationship between photography and feminism prior to the moment in which we grew up, has prompted us to think more about the particular ways in which visual art and the image can be mobilised in relation to today’s feminist demands.

Where it began

The Pavilion, Leeds, 1983

The Pavilion was founded by three graduates – Dinah Clark, Caroline Taylor and Shirley Morena – from the Department of Fine Art at the University of Leeds.

The department was a radical centre of feminist art pedagogy due to the presence of internationally renowned feminist art historian and cultural analyst, Griselda Pollock.

The Pavilion was significant as a space for feminist art which sought to both address the lived realities of women in society and take seriously theoretical and analytical work on the power of images.

The collective established a space for workshops, exhibitions and events with the intention of examining the photographic image and technology in relation to areas of women’s lives ignored in the media image world.

With a darkroom and gallery, The Pavilion exhibited photographic work by leading women artists. But the centre also taught young women in its immediate community in Leeds to make photographs that would define their own representation.

There’s a parallel between The Pavilion and other radical photographic educational projects taking place in the 1980s. Cockpit Arts in Holborn, for example, took a portable darkroom to schools for use by pupils. It’s hard to understand just how radical providing the means of photographic production was – and with it, meaningful debate about the imaging of women – in a time before ‘the selfie’ and social media.

Images do not simply mirror reality – looking at images forms our sense of who we are.

The significance of photography was its potential to give those who did not see themselves represented in the visual world a way to represent themselves. At the same time, this offered a way to critique photography, which dominates the visual media that surrounds us every day.

The Pavilion made space for new kinds of images being produced by women artists. Highly renowned figures, such as Marie Yates, sought to show how images of women were made to present certain false stereotypes of femininity.

Others, such as the women’s art collective, Hackney Flashers, used photography as a form of activism. They took their camera into the workplace to document the often unskilled and low-paid roles taken up by women. Their artwork became a comment on the way in which women’s contributions are undervalued when out ‘at work’ and in the home.

The Pavilion’s focus on the photographic image showed that artistic and cultural practices were just as significant to the activist political work of the women’s movement as other kinds of work on, for example, equal representation for women in training and employment, exhibition space, grants, and screen time. Its call for new types of images asserted that art was not simply a means of visualising politics or illustrating campaigns.

Instead, it demonstrated that the work of art has its own politics: images do not simply mirror reality – it’s by looking at and identifying with images that we form our sense of who we are.

Where it’s going

Art School for Rebel Girls and Pavilion, Leeds, 2017

We based the initial premise of an ‘art school’ for girls on the notion of inclusive spaces which put women and girls at their centre. Such spaces are an important context from which to address and transform the diverse issues women and girls experience – and to counter the masculine perspectives that dominate our culture.

In the 1970s, self-organised ‘consciousness-raising’ groups provided places for women to come together and talk about their lives, feelings and ideas. Consciousness-raising provided a way of linking personal experience to social analysis, as part of the women’s liberation movement in Europe and the United States.

In the 1980s, as at The Pavilion, visual art practices became a process of consciousness-raising. Visual art made visible unseen, unspeakable experiences pertaining to age, race, class, gender and sexuality.

Everyone was an artist, not a future artist or an artist in training.

The world we live in today has many differences to the world thirty or forty years ago. But, informed by this historic feminist activity, Art School for Rebel Girls provided an inclusive space for girls and young people with experience of misogyny to come together on a regular basis as part of a small group working on a range of artistic practices.

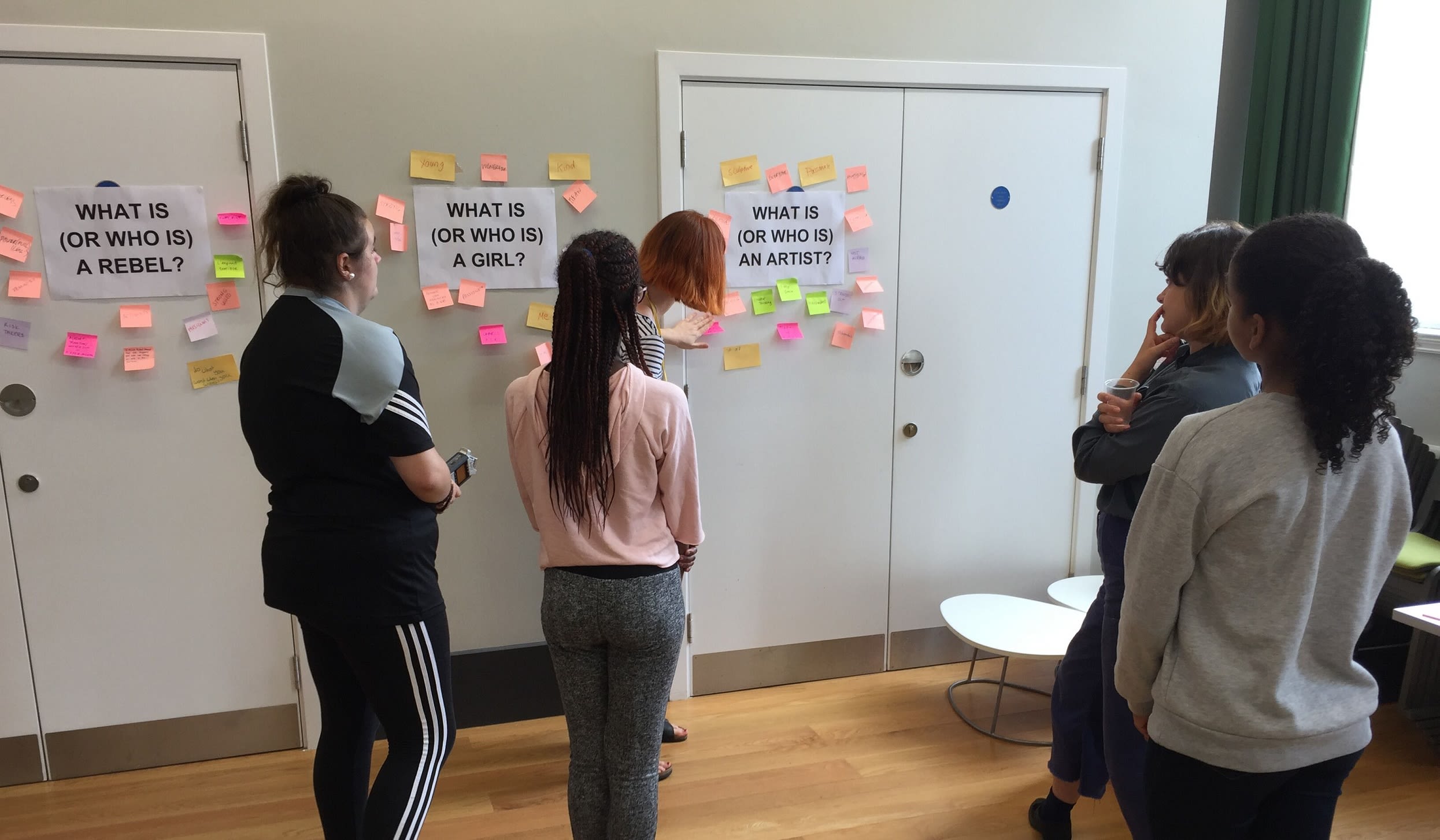

This structure sought to enable the same kinds of self-reflection, intimacy, solidarity and political consciousness for girls that the development of consciousness-raising sought in the women’s liberation movement. Activities focused on the role images play today in setting up and establishing certain identities for girls.

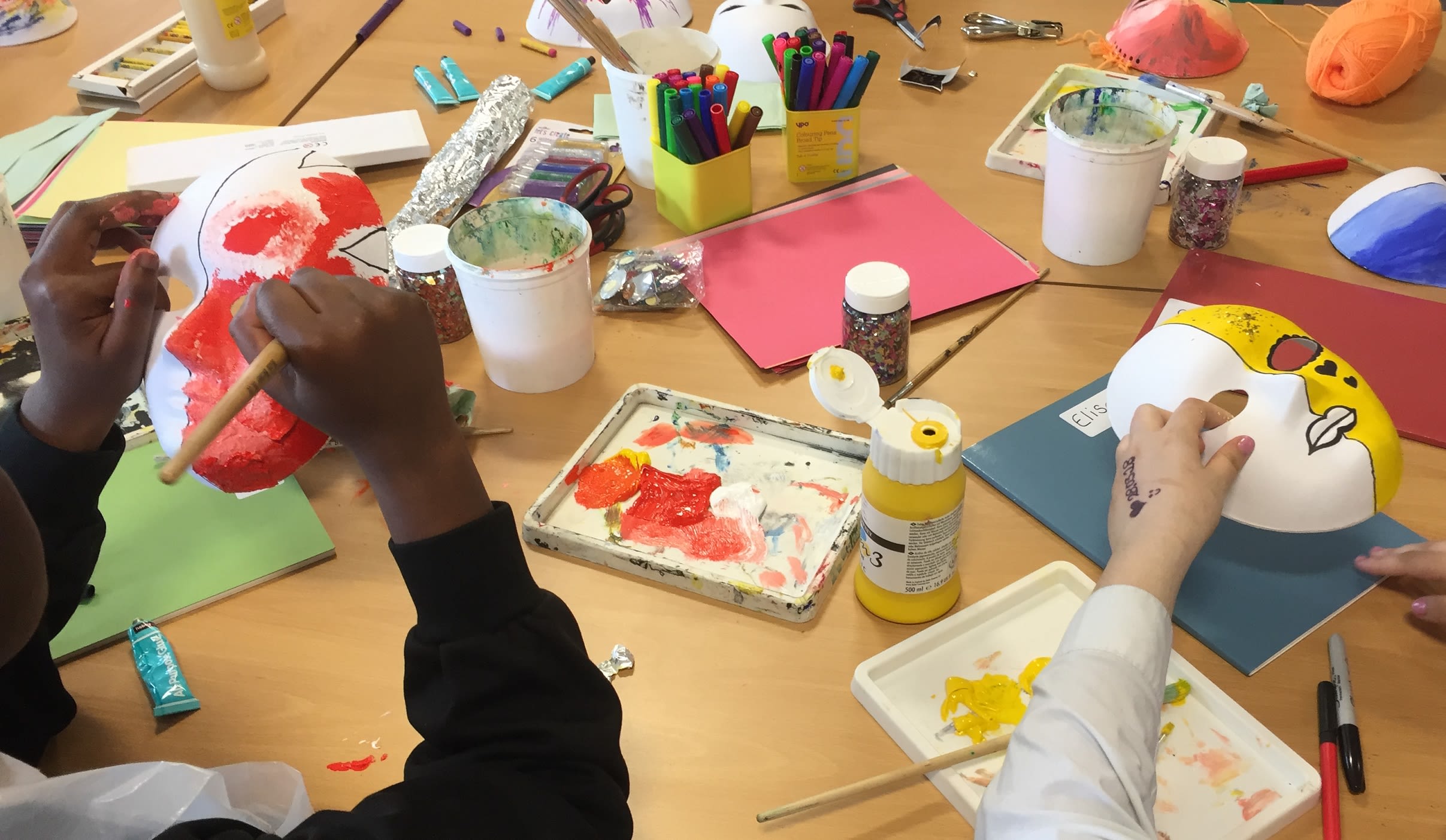

Collaboration was a core dimension of the arts-based workshops. Collaborative ambitions undermine the notions of power and individual achievement which are particularly prevalent in our competitive education system.

Everyone was an artist, not a future artist or an artist in training. We worked together as an intergenerational group to achieve creative aims, inspired by a broad church of artworks by women and non-binary artists rarely included in mainstream curriculums.

Working together to achieve creative aims. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

Working together to achieve creative aims. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

Why girls?

As a group, girls are frequently overlooked. In the UK, there’s a double blind-spot in services, policy, data and research.

Girls tend to be either classed as ‘children’ or subsumed into the adult category of ‘women’, not counted as a specific group of their own. Yet girls, particularly those aged 13 to 16, often experience acute – and traumatic – issues of confidence, achievement and self-esteem.

As The Good Childhood Report from 2017 showed, not only are all children seeing themselves as more and more unhappy, there’s a significant happiness gap between boys and girls. And this only widens as they grow older.

Research over the last year indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this gap, especially for those girls who are the most marginalised and least heard.

Globally, the need to transform the situations of girls has been recognised by organisations such as the United Nations. This has prompted many initiatives that aim to ‘empower’ girls for the benefit of all.

The UN campaign ‘Girl Up’, which initiated the International Day of the Girl held annually on 11 October, is a good example. This day aims to raise awareness of the situation of girls and incite support to remedy it, with a focus on education and empowerment.

Such initiatives predominantly focus on education as a way to break cycles of poverty. There is often an economic agenda: empowering girls is important because it will also lead to economic prosperity for those countries.

However, this proliferation of campaigns, reports and initiatives, which supposedly help girls ‘achieve their potential’, tends not to include feminist critiques of deep-rooted patriarchal and capitalist forms of oppression. Only the surface level issues are addressed. Moreover, they offer a maternalistic / paternalistic top down approach.

What if girls could make their creative mark on the world on their own terms?

Plan UK emphasises a problem with this kind of approach in its State of Girls’ Rights report (2019–20):

“The girls we spoke to are fed up and frustrated with empty words of ‘female empowerment’. They are told they can succeed, but they face a threat to their safety in public, online and in schools. They are told to feel confident in their bodies, but they are judged and scrutinised on every aspect of their appearance. They are told gender equality has been achieved, and yet they do not feel represented or heard in public life.” (Plan UK, p.8)

The report highlights a gap between the discourses that surround girls and the tools that they have access to within culture and society. Being both young and female often constitutes a double discrimination.

Our approach to girl-centred arts activity was prompted by a real need to address such issues.

We took into account how girls and girlhood are overlooked or erased in theory, policy and practice. But we also wanted to find different ways of negotiating power and agency.

Art School for Rebel Girls asked: what would it mean for girls to be taken seriously as cultural producers rather than as merely the subjects of art, film and literature? These were the very questions being asked by The Pavilion in 1983.

Rather than giving girls a voice or place at the table, what would it mean to engage in a collective process finding out what their creative mark on the world might be on their own terms?

We wanted to find ways for girls to be taken seriously as producers of art. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

We wanted to find ways for girls to be taken seriously as producers of art. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

How the Art School worked

Art School for Rebel Girls began as an after-school club. The first job was to establish a rapport between the group in their own classroom, building trust and confidence so that they could participate in activities outside of school (often for the first time).

These off-site activities took place at the University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies. A range of art students, professional artists and curators worked with the girls in the studio and exhibition spaces.

Inspired by the practice of consciousness raising, we wanted studio activities to work through collaboration and across learning, not top-down teaching. We used feminist theorist bell hooks’s concept of ‘engaged pedagogy’ to reflect on personal experience as a way of developing an openness and critical understanding of the world.

Each year’s work culminated in a public exhibition in a gallery with the group acting as artists and curators.

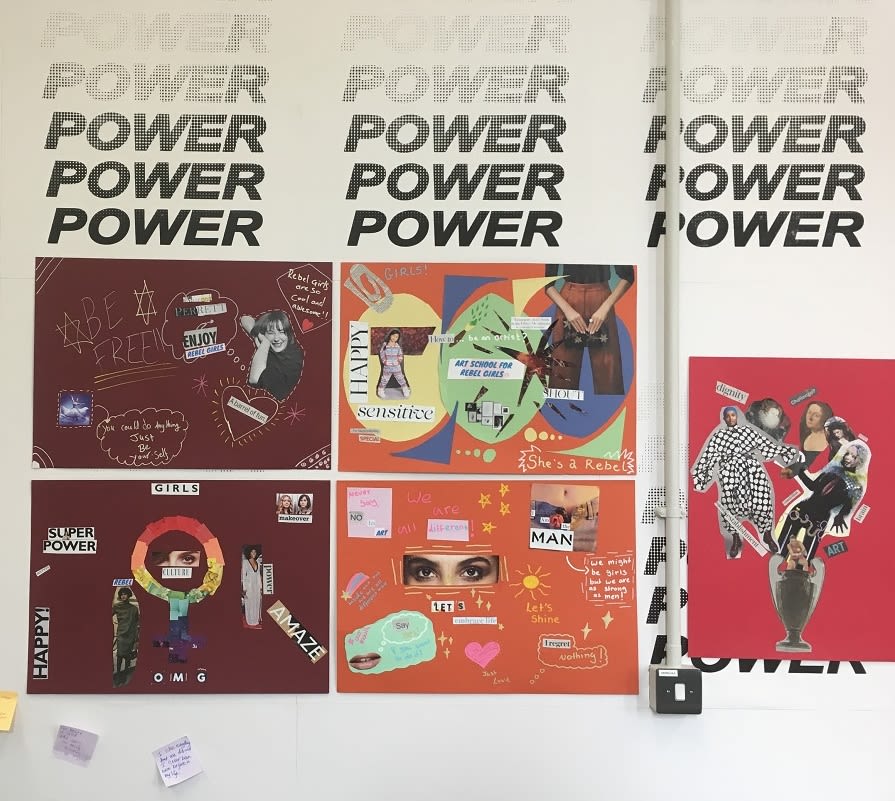

Collages from the 2018 Art School for Rebel Girls exhibition. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

Collages from the 2018 Art School for Rebel Girls exhibition. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

The Pavilion had set an important precedent.

From 15 November–15 December 1988, The Pavilion hosted an exhibition titled ‘5 Women’. This was the result of a workshop series designed to enable local women (who hadn’t been through an art school education) to make photographic work reflecting on their own experiences, positions and representations. One of these five women was Nudrat Afza, who went on to become a successful artist and photographer.

Afza arrived in Bradford from Pakistan at the age of ten. She was interested in photography but, although her girls school had a darkroom, she did not have access to the processes of photography. It was The Pavilion which gave her access to skilled facilitators, dark room facilities, camera and lighting equipment, supportive peers and exhibition opportunities.

Since the 1980s, Afza has continued to use photography to make visible the experiences of girls in the city. Her 1986 photograph ‘Girl with a Doll’ depicts a British Asian girl, standing on the artist’s doorstep in the Manningham area of Bradford, holding a white doll. The photo records the dominant representations of whiteness an immigrant child living in 1960/70s Britain experienced.

Afza’s more recent body of work ‘City Girls’ – exhibited at the National Science and Media Museum in 2018 – consists of 70-plus black and white photographs. These document women and girls cheering in the stands of Bradford City Football Club, making visible the emotions of female fans as well as the diversity and cultural pride of the city.

Mirroring the methods used in 1988, albeit in a very different context, in 2017, Art School for Rebel Girls introduced the group to dark room equipment and analogue photographic processes. Our photo project saw all members of the collective document the activities of the group and their time at home using analogue disposable cameras. Their images were then printed, mixed together and arranged as a collage on the wall of the exhibition.

The focus on analogue technology is perhaps surprising: today’s teenage girls all regularly use digital photography through phones and tablets. But digital photographic technologies and online platforms have strict aesthetic languages and social rules that are not necessarily known to us as adults.

An analogue camera – with viewfinder, shutter release button and film advance wheel – was an alien object to the girls in our group. The idea of winding on film or not seeing an image immediately after exposure was completely strange. With old (yet new to them) analogue processes, the girls were still representing the world from their perspective but with less pressure on how they presented themselves as individuals.

There was no ability to edit images or immediately delete them. As a result, the collage of images produced together of ourselves and each other documented the everyday in straightforward, intimate and experimental ways.

Taking up space

Our work together also explored agency and power by attending to the way each of us takes up space in the world.

In 1980, feminist philosopher Iris Marion Young’s wrote an important account of how women and girls move and carry themselves.

In ‘Throwing Like a Girl’, Young challenges sociological accounts that say girls and boys throw and move differently because girls are naturally feminine.

Yes, girls move differently, she says, but this is nothing natural or innate. Girls acquire and learn subtle habits of ‘feminine comportment’. Significantly they acquire the habit of hampering their movements.

At the centre of Young’s analysis is the feminist philosophical notion that women and girls live their body as an object as well as subject.

For The Pavilion in 1983, using self-presentation as a way to counter the notion of ‘woman as object’ was a key part of a feminist politics.

In a different manner, the kind of work we’ve undertaken in Art School for Rebel Girls embeds this critical problem through physical art making. An extremely simple yet effective way of exploring our comfort with bodily movement and public space is creating large scale collaborative paintings.

We have a lot more space, time and opportunity to do this outside the normal school day. Many young artists may at first be fazed by the materials or the scale given over to them. But, given the time and the space, they soon find new and interesting ways to work.

In this case it was taking the challenge of large scale working and large movement with their bodies. The first time we tried this in the Art School for Rebel Girls became an unforgettable and iconic paper work: ‘the big mess’. On its completion, we went back to trace and analyse the movements and marks on the paper and how we’d felt when we were making them.

Art gives girls the confidence to be agents in the world. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

Art gives girls the confidence to be agents in the world. Image: Elspeth Mitchell, courtesy of Pavilion

Art has a vital impact

By making visible The Pavilion as an important pre-history for Art School for Rebel Girls, we wanted to show how the development and transmission of arts education concepts and practices engaged with feminism emerged from the city of Leeds and the University of Leeds from the late 1970s onward.

There are methods within feminist histories that remain useful to us now, and this sense of valuing feminist work is part of a feminist methodology of knowledge production.

Today, the University of Leeds, the city of Leeds and its surrounding area of West Yorkshire, continue to be an important place for artists and cultural theorists engaged in a feminist politics and practices.

The Art School’s approach chimes well with the University’s ambition to change existing academic culture from one of competition to one of collaboration. Under its new strategy for 2020-30, the University has also reinforced its commitment to making a real difference in its local community and to welcoming underrepresented groups. The ambition of the University is for its work to make a real difference in the real world.

Current government policy has marginalised and disregarded art subjects within the school setting. But art isn’t subordinate to the STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths) – something simply fun or frivolous. It’s a vital means of supporting girls to be agents in and of the world.

Art School for Rebel Girls shows how educational projects, rooted in collaborative visual art practice, can produce ways of working that positively impact the rights and lives of young women in contemporary society.

While feminist histories continue to inform and transform the present, future work must continue to challenge the persisting inequalities that girls are up against.