The race to revolutionise travel

A multi-university team – with development led by Leeds – has built a tool that's helping to shape the future of transport and create a sustainable future.

As a child, Robin Lovelace was fascinated by the scale and wonder of nature documentaries. But he was alarmed to learn that many species and habitats were under threat.

Why were rainforests being cut down? Why were we polluting the atmosphere with fossil fuels? These injustices troubled him. He felt like an observer in an ecological crisis that was being largely ignored.

What could he do to make a difference?

Seeking a solution

The urge to tackle the climate crisis played on his mind throughout his studies. By the time Robin had completed his PhD in Transport and Energy, he’d formed the beginnings of an idea that might help.

How we get around has a direct impact on climate. Transport is a major carbon-emitting sector, and is responsible for about a quarter of UK carbon emissions. It’s also proven to be the most difficult sector to decarbonise.

In the UK, around 2% of trips are made by bike, compared with 28% in the Netherlands. Using this data, Robin had the idea to map effective, viable cycle routes with open-source software. It would show where cycling is already happening, but more importantly, it would illustrate where it could grow.

Such evidence could help direct investment in cycling where it’s most needed – hopefully putting the brakes on high-energy modes of transport, reducing traffic congestion, and increasing physical activity for millions of people – with huge health benefits.

He knew it was a great concept, but could it become a reality?

A decarbonising cycle

Robin talked about the idea to many people, yet he made little progress with his “algorithm to prioritise cycleway investment”.

Then, by chance, a colleague revealed that the Department for Transport was looking to commission a tool to steer planning and policy. It seemed like the perfect moment to get involved.

“So there’s interest in this,” he thought. “Maybe we can make it happen.”

Robin knew he couldn’t pitch the project alone, so he reached out to more experts in the field. One of those was James Woodcock, Professor of Transport and Health Modelling at the University of Cambridge.

With James on board, they rapidly assembled a skilled team, including Rachel Aldred at the University of Westminster and Anna Goodman from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Together, they made a bid for the project.

The team knew they lacked experience in central government contracts, so expectations were low. What happened next was surprising, and posed an unexpected problem.

Conflicting opportunities

Several weeks passed. Then the call arrived:

“Congratulations, the team has been awarded the Propensity to Cycle project.”

Robin’s delight switched to panic. The project was now a reality, but it clashed with something else: his new full-time job.

Months earlier, he’d committed to working with Mark Birkin in the Consumer Data Research Centre at the University of Leeds. On his first day in the role, Robin found himself apologising for somehow taking on two full-time positions – far more than he could manage long term.

“We’ve accidentally won external funding,” he explained to Mark. “But I honestly didn’t think we’d get it.”

For a time, he found himself stretched across both roles, but Mark was supportive and understanding. He soon secured funding to hire more people, releasing Robin to focus on the Propensity to Cycle Tool.

Software and soft skills

The wheels were finally in motion, but it was a challenging period. Robin’s passion for the work drove him through long evenings of coding and longer exchanges with the team. As he discovered, it would only get harder.

Working in an online environment – and communicating at a distance through video conferencing – presented unexpected human challenges. Crossed wires, misinterpreted body language and screen fatigue often scrambled the best of intentions.

But after two exhausting months, the team had something to present to the Department for Transport. It was far from what they had expected.

A transformative tool

Based on previous projects delivered by large consultancies, the Department for Transport was expecting little more than a PowerPoint presentation.

What the team delivered was an early, near complete version of the national Propensity to Cycle Tool: a web application that calculated the potential for people to switch modes, primarily from car to bicycle. Interactive maps also showed how to deliver a cycling infrastructure where it was most needed.

The Department for Transport immediately saw the huge value in the prototype, which led to the funding of a scaled-up, national tool.

There was much to celebrate in the team, but Robin’s mind quickly focused on a difficult decision he knew he’d have to make – and it involved his own place, and future, on the project.

Further together

Developing the Propensity to Cycle Tool into a nationwide project was daunting.

New funding forced Robin to answer one the biggest questions of his professional life: should he continue to go it alone in Leeds, with support from the rest of the team in the South of England, or recruit and lead his own group in the Institute for Transport Studies?

Expanding would mean relinquishing some control and managing new people, alongside continued collaboration with the teams in Cambridge, Westminster and London.

It was a tough decision. But he knew, as a larger group, they could go further together. So he did something outside of his experience, and went through the process of hiring and becoming a leader.

One of the people recruited was Malcolm Morgan, and over many months they worked closely to help deliver the latest iteration of the Propensity to Cycle Tool. Robin knew he’d made the right decision: together, they encouraged each other to try new approaches that would not have been explored in isolation.

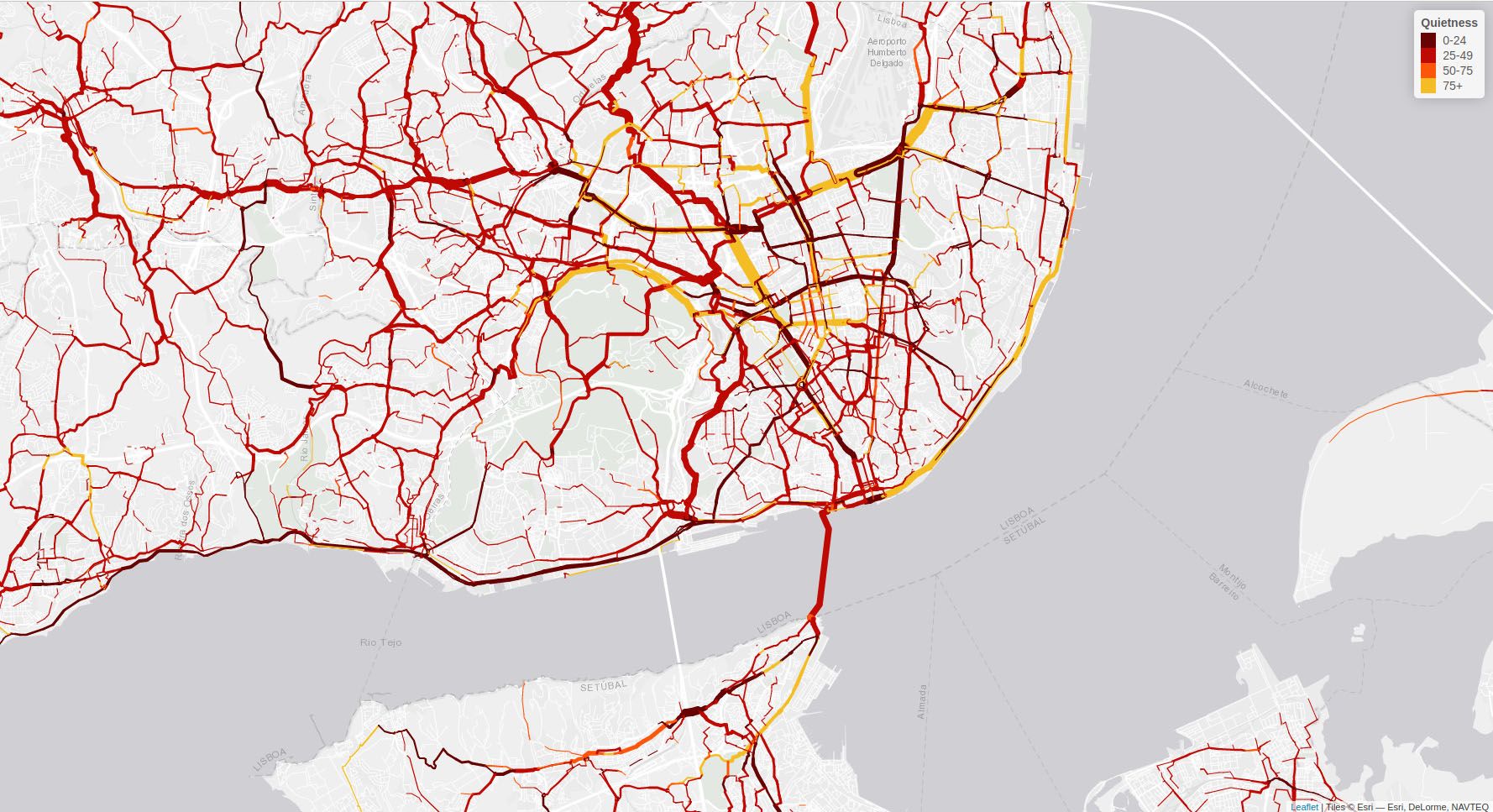

Map showing estimates of cycling potential on an international scale (Lisbon, Portugal). Credit: Rosa Félix and team. Source: 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-4-W1-2022-279-2022

Map showing estimates of cycling potential on an international scale (Lisbon, Portugal). Credit: Rosa Félix and team. Source: 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-4-W1-2022-279-2022

Finally, the tool was ready for release, and it would send shockwaves through the transport planning world. It was mentioned in the House of Commons, and was highlighted by the Secretary of State for Transport in the Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy.

But for Robin, the successful delivery of the tool was only the start. Now it needed to reach those who needed it most.

Open-source software and citizen science

Throughout the whole process, Robin was keen to share their tool so it could have the widest reach and impact in the real world.

His approach differed from competitive attitudes of the time. It meant making a national tool, funded by the Department for Transport, freely available as an online resource. The team agreed: the wider the access, the broader the impact would be.

Today, government, agencies, politicians, and developers have free access to the Propensity to Cycle Tool. Transport planners, consultants, and advocacy groups are using it to develop more evidence-based and cost-effective cycle network plans across the country.

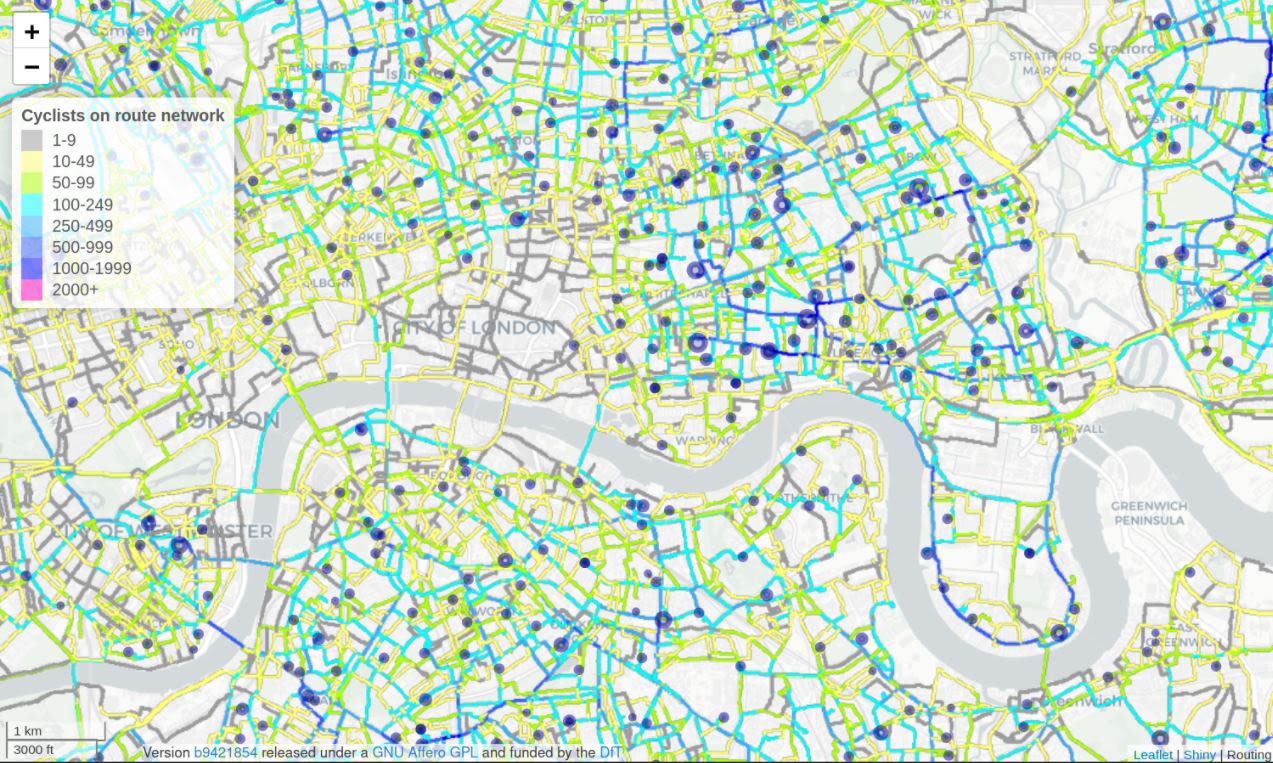

Map from the Propensity to Cycle Tool showing potential uptake of cycling to school in London. Source: doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.01.008

Map from the Propensity to Cycle Tool showing potential uptake of cycling to school in London. Source: doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.01.008

The tool has influenced hundreds of millions of pounds worth of investment, and benefited millions of people by providing safer and more joined-up cycling routes. It’s even being used in schools and educational engagement programmes.

Robin’s passion to revolutionise transport came from a child’s desire to make a difference. Now the Propensity to Cycle Tool has come full circle and is inspiring a new generation of young minds to seek climate change solutions, and contribute their own ideas for a sustainable future.

About Robin

Robin Lovelace is Associate Professor of Transport Data Science at the University of Leeds.

His research interests include open-source software, data science, geocomputation and transport modelling for more participatory and evidence-based policy making .

Visit the Propensity to Cycle Tool website.

Read the Research Excellence Framework case study for the Propensity to Cycle Tool.

Read the original paper describing the Propensity to Cycle Tool.