The

power

of

words

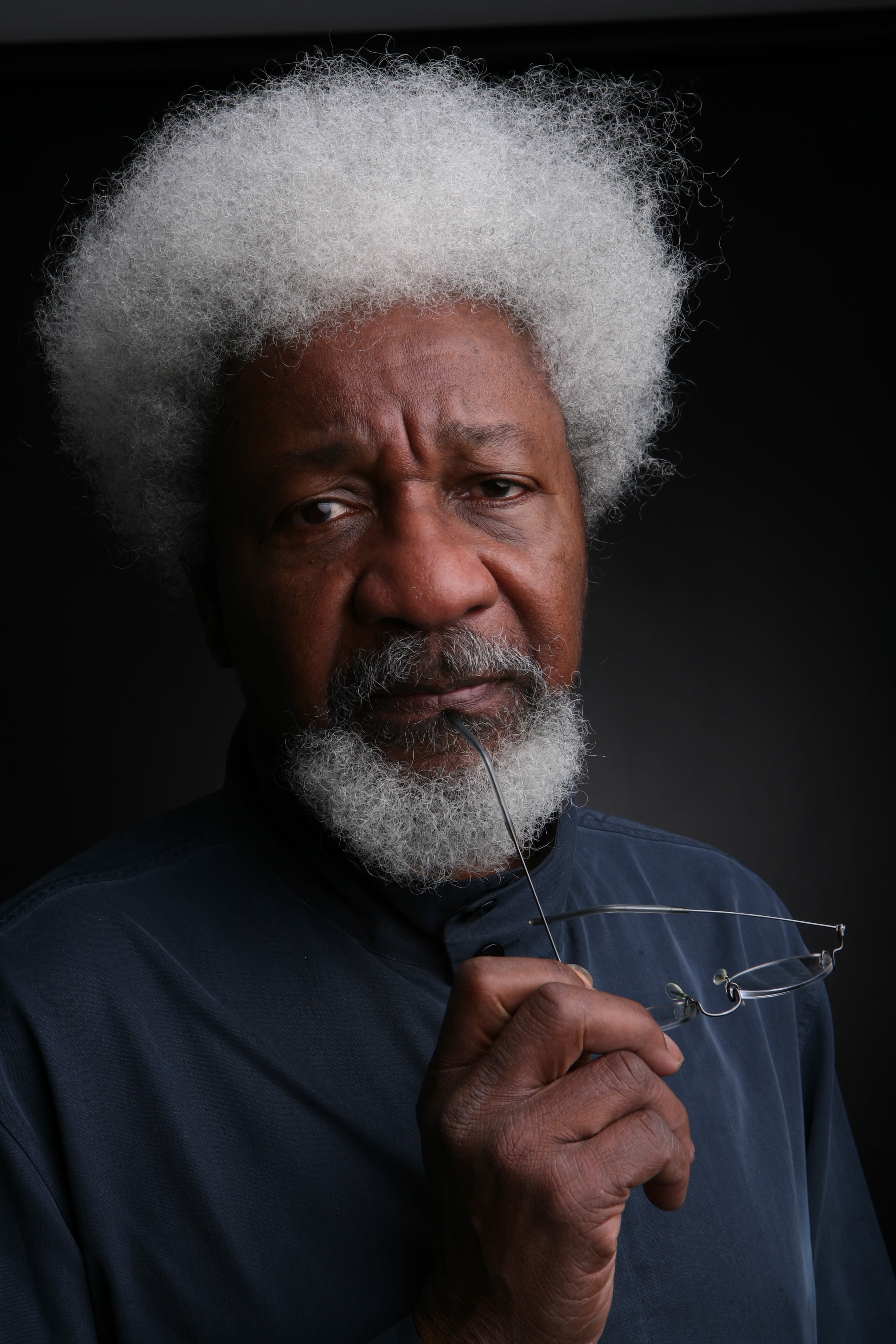

Alumni feature: Wole Soyinka

As a child, Wole Soyinka was nicknamed “the questioner”. It’s a trait that has emerged time and again in a life that has seen him both feted and condemned. Deep into his ninth decade, the Nobel prize-winner continues to question the world around him.

Wole Soyinka stole a pen from the prison doctor’s pocket. Some would call it theft. Others, salvation.

A turbulent decade after he graduated from Leeds, Nigeria’s federal military government had sent Wole (English 1957, Hon DLitt 1973) to prison without trial for speaking out against the country’s dictatorship and the civil war in Biafra.

Wole spent 22 out of 26 months of his imprisonment in solitary confinement. He occupied his mind by composing and memorising short and self-contained poems, ready to pounce when a scrap of paper manifested itself. He already had the pen.

These scraps, these “prisonettes”, reflect Wole’s drive and determination to write. They were somehow smuggled out of his cell and eventually landed at the University, which also holds writings from Wole’s more light-hearted student days at Leeds. The works long precede his 1986 Nobel prize in literature and his profound influence on today’s flourishing crop of successful African writers.

Through his harrowing life as a political prisoner, Wole clung to the power of his words to call his captors to account. In his book about the experience, The Man Died, he wrote: “Books and all forms of writing have always been objects of terror to those who seek to suppress truth.”

Wole’s deep commitment to speaking truth to power underpins his writing, which includes more than 30 plays, three novels, volumes of poetry, major critical essays, autobiographical accounts, films and translations.

Sixteen paces

By twenty-three.

They hold Siege

against humanity

And Truth

Employing time to drill through to his sanity.

At the age of 87, he is a towering intellectual figure in a country that has imprisoned him, sent him into exile and sentenced him to death. He’s called out Britain’s colonial role in his country’s history and is an important symbol of the opposition for many in Nigeria and, indeed, across Africa.

Since 1975, Wole has lived the life of an academic, commentator and a creative force both in Nigeria and abroad. Now he is back on familiar ground, once again witnessing and commenting on turbulent times.

Wole, who is most comfortable writing drama, astonished the literary world with the recent release of his third novel, a satire of contemporary Nigeria.

So why, after 48 years, write a novel? In an interview with PEN America, he said that no other writing form suited the sweeping turmoil in his country: “The bubble had to burst and spatter all over the place and only the prose form, the fiction form, could contain that spattering.”

Hence, his “gift” to Nigeria, his book Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, a cutting look at the nature of greed, betrayal and power. Chronicles is a novel of hope and cynicism, of murder and mayhem, and like all Wole’s work, is full of wit, insight and poetic beauty.

Part whodunnit, part brutal satire, it includes fictionalised versions of prominent contemporary Nigerians.

The genesis for the novel came, he told PEN, when: “watching one’s own environment, in which one grew up, from which one drew one’s inspiration, developed one’s values related to other people ... just watching all that decay around you in a most violent way – not even a gentle slide into decadence, but violently.”

Just where did Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka develop his values?

Wole was born in Abeokuta, southwestern Nigeria, in July 1934. Aké, the first book in his acclaimed series of autobiographical works, offers an exuberant account of his childhood. His father was a primary school headmaster and Anglican minister. His mother owned a store and was active in the women’s movement.

He was surrounded by a rich mix of traditions – from the tribal rituals, tales and legends of his family’s Yorùbá culture to the stories told by women meeting at his house; from Christian stories, sermons and hymns to the everyday dramas of school and family life.

“I grew up in a really exciting atmosphere of political activism on one hand and more staid political discussions which went on around my father,” Wole told the Academy of Achievement. “They’d debate everything from the world war that was going on at the time to the price of newly-introduced motorcycles.

“The exchange of ideas between adults fascinated me,” he said. Unlike other children, Wole’s presence was indulged by the elder speakers who gave him a prophetic nickname: “I was known as the questioner.”

He still speaks fondly of his years in Leeds, mischievously calling them his “rascally times”.

At the age of 11, Wole travelled to Ibadan to complete his university preparatory studies, focusing on English, Greek and history. He then came to Leeds to study English literature. He still speaks fondly of his years in Leeds, mischievously calling them his “rascally times”.

He last returned to the University in 2015 to give the Leeds Centre for African Studies Annual Lecture, in which he argued that much of the contemporary violence in Nigeria was underpinned by the complete repudiation of dialogue.

At that time, Wole offered a vivid sense of the unique student life of late 1950s Leeds where he met eminent poets and playwrights-to-be Tony Harrison, James Simmons and Geoffrey Hill; Marxist literary critic Arnold Kettle; budding comedian Barry Cryer and many others.

Wole spoke of the great teachers at Leeds and described how he explored the city, visiting “religious institutions of every denomination” to explore spirituality. He explained how the wooden carvings on church pews in Leeds, for instance, helped him see a kind of equivalence with wooden carvings in Nigeria, and how this made him question received knowledge about primitivism.

Wole published his first short story, Madame Etienne’s Establishment, in The Gryphon in March 1957. His early plays are sometimes known as “the Leeds plays” because initial drafts were made during his time in the city. After Leeds, Wole became a dramaturgist at the Royal Court Theatre in London. This was a formative time that Wole recalled in his powerful Nobel lecture in 1986.

Stay connected with your university

Update your contact details and change your communications preferences to stay connected with Leeds.

Wole returned to Nigeria in 1960 to study African drama and teach at universities in Ibadan, Lagos, and Ife, before landing in prison. After his release in 1969, he became Head of the Department of Theatre Arts at the University of Ibadan until he had to flee into exile.

At Ibadan, he was close friends with Martin Banham, who would later become a professor at Leeds and establish the Workshop Theatre on campus. Martin gave the University a collection of materials linked to Wole. Of particular interest are the papers relating to Wole’s friendship with Rex Collings, an important English publisher who campaigned tirelessly for his release from prison. Wole’s prison poems are part of this collection.

Wole returned to Nigeria in 1975 but left again in 1994 when the military head of state Sani Abacha confiscated his passport, and later sentenced him to death. When Abacha himself died in 1998, Wole finally returned home.

Countless critics have proclaimed Wole to be one of the most creative and exciting playwrights in the English language. The 1986 Nobel prize judges characterised him as “one of the finest poetical playwrights that have written in English”.

His plays are rooted in the rich theatrical traditions of the Yorùbá people of western Nigeria. They are vivid, colourful, fierce, funny and haunting. The early plays offer a gentle satire and reflection of the tensions of a rapidly changing Nigeria while boldly exposing injustice and corruption.

By the 1970s, Wole’s satire had become fierce and angry, and sometimes full of contempt. Only last year, a performance of Wole’s play Death and the King’s Horseman, directed by his friend Bolanle Austen-Peters, saw a Lagos audience cheer and cry their way through a work written four decades earlier. Set in 1944, in the ancient Yorùbá city of Oyo, this philosophical drama has provoked extensive debate about anti-colonialism, political integrity and the need for critical dialogue between European and African cultures.

A remarkable range of activity by young writers, from Yorùbá Opera to new playwriting, has been inspired by Wole’s work as a theatre director and teacher. He founded acting companies that have given young actors and new audiences the chance to see and participate in works of national and international importance.

A master of many literary forms, Wole demonstrates that artists do not have to choose between aesthetics and politics. It is possible to write meticulously crafted, creative works that are simultaneously committed to justice, integrity, compassion and equality.

In his prison memoir, he famously wrote: “The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.” His latest novel reflects a lifelong commitment to speaking out in the face of injustice, inequality and corruption, and powerfully demonstrates the enduring role of literature in working towards a better, fairer world.

What did you think?