CHAIN REACTION

A scholarship was the foundation of David Fine’s career in explosives detection. Now his support provides life-changing opportunities for students and staff from his native South Africa.

“I’ve been blowing things up all my life,” says David (PhD Physical Chemistry 1967). His career in invention, enterprise and discovery has touched fields as diverse as medicine and food safety, brewing and laser hair removal.

But it’s for his work in explosives and landmine detection that David is best known. His team developed the first sniffer devices for explosives and narcotics, and combined radar and metal detection to create a handheld landmine detector. His work on explosive residues was used to identify the Semtex used in the Lockerbie bombing. He holds more than 100 patents and has published a host of papers on environmental hazards and carcinogenic compounds.

This extraordinary career began in Leeds. “My first degree was at Wits University in Johannesburg and I won a scholarship to study in Leeds,” he says. “Coming to England was a big deal back then – a two week boat voyage – but I was determined to study under Fred Dainton, one of the top nuclear scientists of the day.”

Those plans were soon derailed: “As soon as I arrived, Professor Dainton left to take up a post at Nottingham University, so I switched to study combustion under Peter Gray, Professor of Physical Chemistry.”

He admits to having misgivings about his ability to succeed at Leeds: “I was with people who knew a lot more about the subject than me and I wasn’t sure I'd make the grade. But this is where things really began for me, learning about combustion, how explosions happen and how these runaway reactions occur.”

He describes a city very different to the one of today: “The buildings were black from the soot and the smogs so bad that sometimes you couldn’t even see your own feet. You could hear people, but not see them.

“Unlike in South Africa, there were no supermarkets. We went shopping at the fishmongers, the fruit and vegetable shop, the butchers. And very few people had telephones because there was a shortage of lines. When my wife had complications with her pregnancy, we finally managed to get one installed.” The couple’s daughter Karen, a vet and bestselling author, was born during their time in the city.

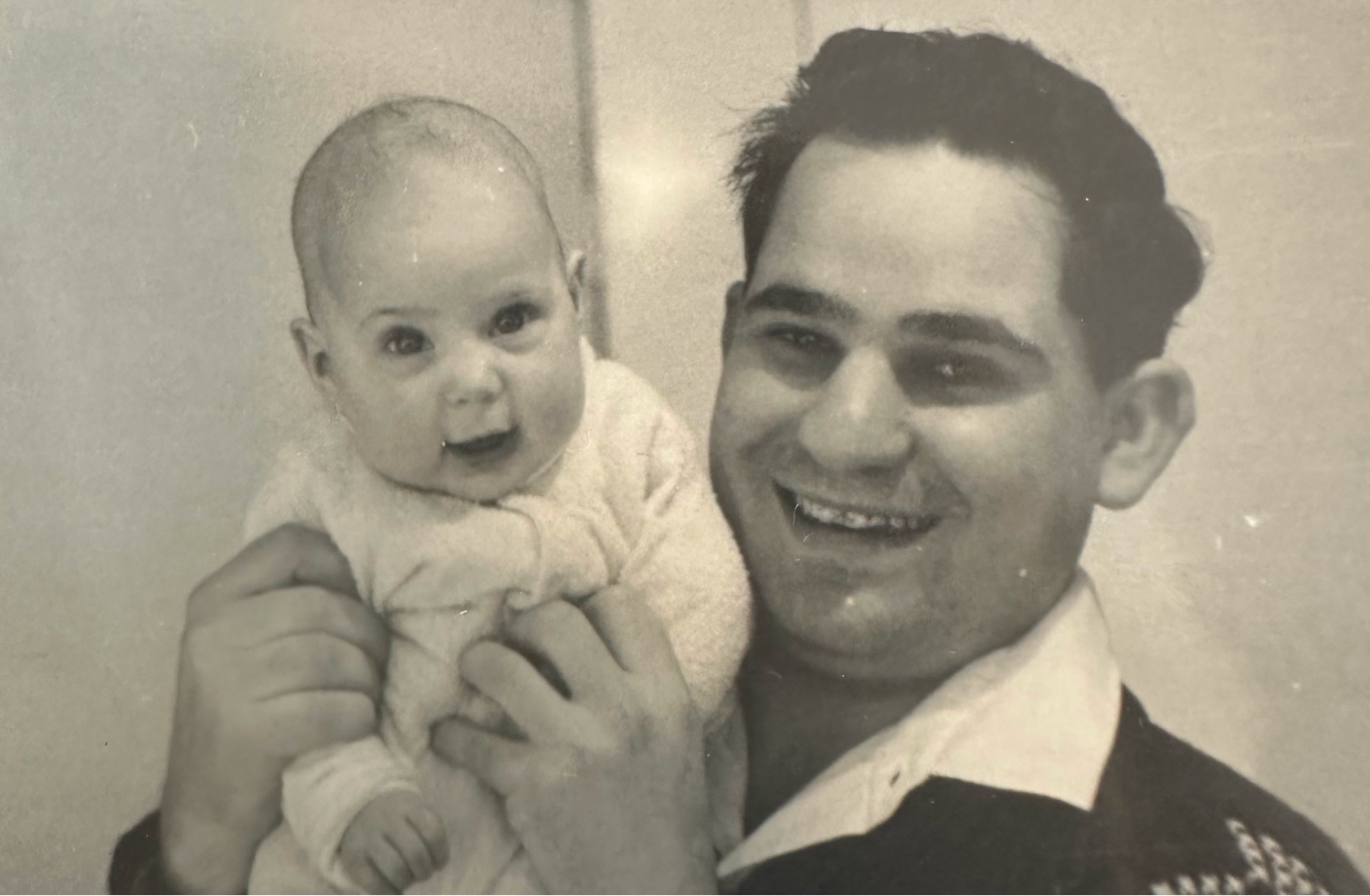

David Fine pictured during his time at Leeds with his daughter Karen

David Fine pictured during his time at Leeds with his daughter Karen

After completing his doctorate David's next role was less successful: “I went into a research post in Canada – and they asked me to create something that simply wasn’t possible. It wouldn't work. I ended up being sacked for alleged incompetence and stupidity.”

But on Peter Gray’s recommendation David quickly secured a job at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) managing PhD students in chemical engineering. He later ran MIT’s combustion laboratory before moving into industry with biotechnology giant Thermo Electron (now Thermo Fisher) where he worked for 28 years, and where he started his own research department. “They didn’t mind what we did, as long as we were bringing in money,” he laughs.

An early discovery led to a change in brewing: “We found that many beers contained cancer-causing compounds called nitrosamines as a direct result of how barley malt was roasted over open fires. Changing the process has solved that issue worldwide. We also worked alongside Home Office scientists to develop the scanners that you go through when you're at an airport. As a result, it’s been a long time since someone has managed to take a bomb onto an aeroplane.”

Through his company, CyTerra, David turned his attention to landmines by developing a device combining ground penetrating radar with sensors to detect TNT vapour. These are now used in war zones worldwide. In 2006 he established GeNO (now Vero-Biotech) which developed a new treatment for pulmonary hypertension.

David hopes to now foster this spirit of invention among those awarded the Gray and Fine Fellowships, whose name also acknowledges the formative role Professor Gray played in his own career. The Fellowships are enabling staff and students from Wits to work alongside colleagues in Leeds, allowing those from both institutions to deepen their understanding of their field while tackling issues from a fresh point of view.

Gray and Fine Fellows from Wits shared their research insights and established new partnerships with colleagues from other institutions at the Global Academy event held in Leeds in January.

“I learned so much, coming from apartheid South Africa to Leeds. People living and working in different places see things very differently, think very differently. What better way to promote innovation than to let students and staff from South Africa and Leeds examine each other’s problems from their own perspectives and work together to solve them?”

Seven Gray and Fine Fellows were funded to attend the Global Academy event in Leeds in January. The Academy is a platform for researchers worldwide to come together to develop skills and ideas and build relationships with others from across disciplines and international borders.

“I have always been fascinated by innovation and why do some people do it and some don’t? The person lucky enough to have the breakthrough is often not the expert. They might be from a different field, or just a naïve newcomer who stumbles upon it by accident.”

He cites the example of Alexander Fleming. “He discovered penicillin almost by accident. He was examining swabs for doctors, but mould had drifted up from another lab and killed all the bacteria in one of his petri dishes. Instead of simply throwing it away as a failed sample, he realised the mould could be grown and used to treat bacterial infections.

“With many innovations, there is this element of pure luck and serendipity – the right person being in the right place at the right time.

“But you must have the strength to push back and stand up for your work. In research, if you are not failing, you're never going to invent anything or push back the forefront of knowledge.

“Leeds taught me how to think like this.”

Professor Nick Plant

Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Research and Innovation, University of Leeds

We are grateful for the support of David Fine, who is enabling the creation of a dynamic community of people who can work together to solve the problems of today.

Dr Songeziwe Ntsimango

Lecturer in Organic Chemistry, Wits University

The Fellowship has given me the opportunity to form collaborations with other chemists outside of South Africa and to establish interdisciplinary research partnerships tackling other real-world problems.

Dr Phelelani Mopanza

Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, School of Governance, Wits University

We’ve been discussing

collaborations in engineering, health sciences, economics and other fields. It’s been a really great experience for partnerships and research outputs.

Dr Letitia Pillay

Senior lecturer in the School of Chemistry, Wits University

Being here has allowed me to think a little bit more about aspects of my research that intersect with other people’s. Having the

opportunity to come across here and experience this has been absolutely fantastic.