Tackling cancer together

Leeds Cancer Research Centre

Despite major improvements in diagnosis and treatments, cancer still kills around 10 million people a year worldwide. The new Leeds Cancer Research Centre is bringing together more than 250 scientists and clinicians from across disciplines to put Leeds at the forefront of global efforts to tackle the disease.

“Curing cancer remains one of the biggest global health challenges. Over the past 40 years survival rates have improved from 30 to 54 per cent, but even so it kills around 450 people a day in the UK alone.”

David Sebag-Montefiore, Audrey and Stanley Burton Professor of Clinical Oncology and Health Research, leads the new Leeds Cancer Research Centre (LCRC): “There’s a great deal more to be done,” he says.

Around the world, the approach to cancer research is changing, recognising that collaboration between disciplines and across international boundaries is critical to accelerating progress in the lab and impact in the clinic. The Centre will harness outstanding strengths from across the University and Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust to develop world-leading research that will accelerate and deliver new treatments and technologies to improve patient outcomes.

By bringing together experts in biological, physical, engineering and clinical sciences, the Centre will enable a vibrant interdisciplinary community that will push the boundaries of cancer research, and train future cancer research leaders.

With access to some of the most advanced experimental facilities in the world and a combined funding portfolio of around £125 million, this remarkable community is ideally placed to develop new diagnostics, and improved technologies and treatments, to transform patient care.

Promoting world-leading interdisciplinary research – Centre Director David Sebag-Montefiore

Promoting world-leading interdisciplinary research – Centre Director David Sebag-Montefiore

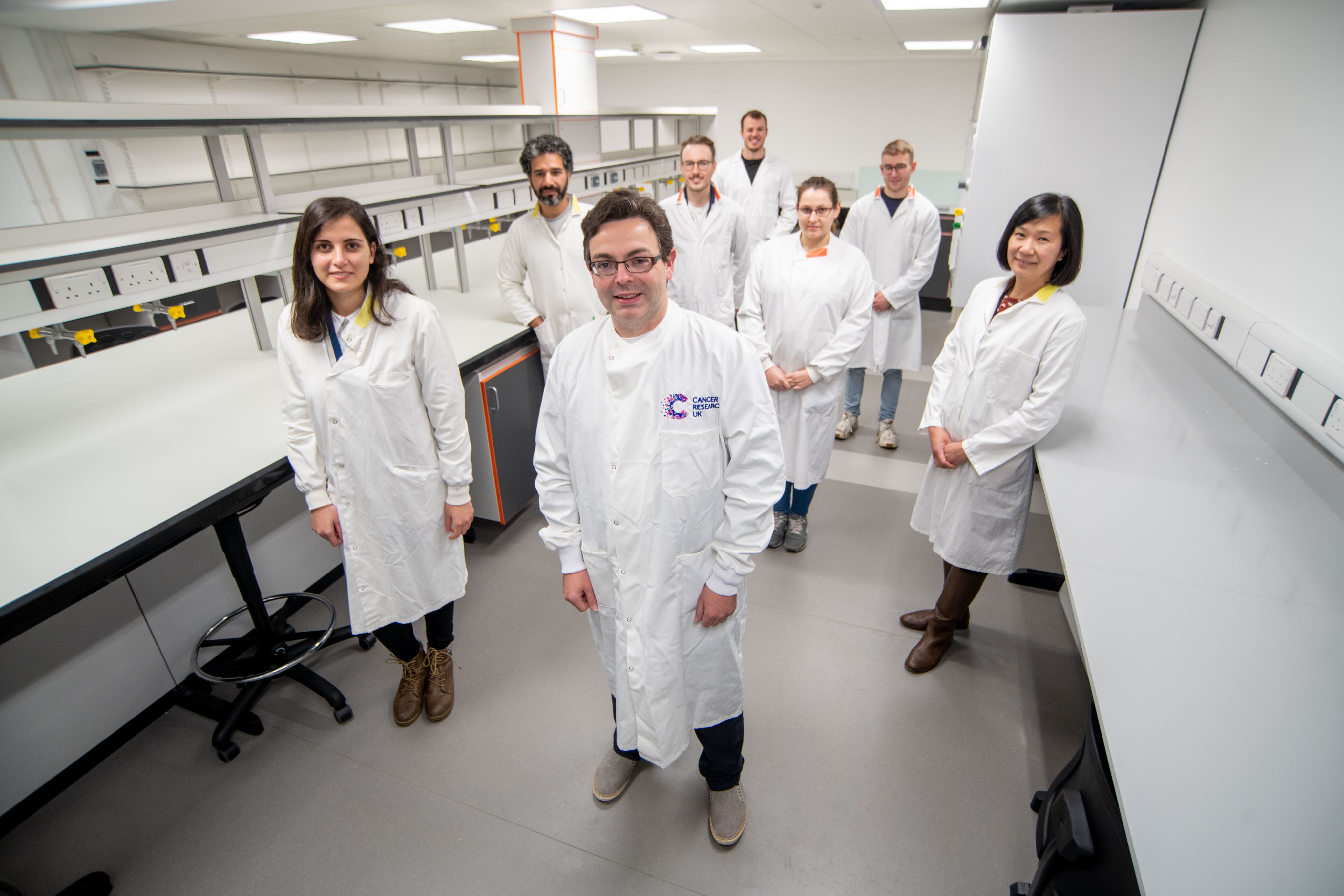

Research in the University’s Astbury Centre for Structural Molecular Biology studies the biological mechanisms at work in cancers, both to better understand how treatments can be improved and to identify new targets for future drug development. Richard Bayliss, Professor of Molecular Medicine, explains: “By understanding the molecular structures that underpin the biological behavior of cancer, we can work with other disciplines to accelerate the development of new treatments.”

Research in the Bragg Centre includes using robotic technologies to diagnose and treat cancer. In one project, scientists are developing robots with “magnetic tentacles” to probe deep inside the human body. Guided by external magnets and 3D imaging, they will biopsy difficult-to-reach cancers, allowing doctors to make an early diagnosis – and give patients the best possible chance to beat the disease.

Working together to understand cancer mechanisms and develop new treatments – Richard Bayliss and his team

Working together to understand cancer mechanisms and develop new treatments – Richard Bayliss and his team

Leeds is tackling health inequalities across the region, home to around three million people, 17 per cent of whom live in areas of severe social deprivation. The Yorkshire Lung Cancer Screening Trial is one of the largest of its kind in Europe. Funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research, it takes mobile scanners into shopping centres and car parks to screen patients at risk of lung cancer. So far, more than 100 cases have been detected, allowing patients to receive early treatment.

Training our future cancer research leaders

Training the next generation of cancer research leaders is at the heart of the Centre’s mission. The University has outstanding research training programmes that are critical to realising this mission, including the Integrated Clinical Academic Training programme, the UKRI Centre for Doctoral Training in Artificial Intelligence for Medical Diagnosis and Care and the University Academic Fellowship scheme.

The LCRC will grow its diverse community, increasing access for those who have not had the opportunity to demonstrate their research potential. Says Adam Nelson, Professor of Chemical Biology: “We will equip a new generation of diverse research leaders by instilling a culture of collaboration, and giving them the essential expertise, tools, technologies, leadership and ambassadorial skills to become the cancer leaders of tomorrow.”

Susan Short, Professor of Clinical Oncology and Neuro-Oncology, is leading a major clinical trial funded by the Brain Tumour Charity to evaluate combining chemotherapy with a cannabis-based mouth spray for patients with recurrent glioblastoma, a highly aggressive brain cancer. Around 2,000 people in England are diagnosed with glioblastoma each year, and are treated with surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. “Even so, nearly all these tumours re-grow within a year,” says Susan. “Unfortunately, there are very few options for patients at that point.”

The trial will study the use of the drug Sativex, which contains two cannabis derivatives. It is hoped the treatment could delay progress of the disease and improve patients’ quality of life. The recent designation as a Tessa Jowell Centre of Excellence for brain cancer research recognises Leeds’ substantial contribution to tackling one of the most aggressive cancers. In 2016, many alumni responded generously to our appeal to support Susan’s work tackling this devastating disease.

Developing new approaches to treating brain cancer – Susan Short

Developing new approaches to treating brain cancer – Susan Short

Leeds Cancer Research Centre (LCRC) continues the city’s long and rich heritage in cancer research, which includes pioneering research by Professors Moynihan and Golligher, known as the “godfathers” of abdominal and cancer surgery.

The National Radium Centre was established in the 1920s at Leeds General Infirmary, relocating to Cookridge Hospital in the 1950s to establish the regional cancer centre.

And the Centre comes at an important time. Cancer cases are predicted to rise steeply in the years ahead – due both to our longer life expectancy, improved screening and diagnosis, and delays in cancer diagnosis caused by Covid-19.

Its work will tackle some of the major challenges of the years ahead: “I’m passionate about bringing together the best minds from traditionally distinct disciplines to solve the big research questions that will improve the lives of our patients,” says David. “This simple and powerful objective is at the heart of what we are doing.”

Did you know?

The use of Tamoxifen, a hormone therapy that has transformed the lives of breast cancer patients worldwide, was developed by Craig Jordan (Pharmacy and Pharmacology 1969, PhD Pharmacology 1973, Hon DMed 2001).

We explore three examples of world-leading research from Leeds.

Targeting the deadliest cancers

Leeds scientists have uncovered a new way to target a mutant protein that can cause the deadliest cancers.

RAS is a protein important for health, but in its mutated form, can lead to the growth of tumours and make cells resistant to cancer treatment. Mutated RAS is associated with over half of all bowel cancers, and nearly all pancreatic cancers. There is only one licensed drug currently available, and it is only effective for a minority of patients.

Now a team from the University has found a new way to target the protein to pave the way for a greater range of treatments for more patients.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, Technology Strategy Board and Avacta, and published in the journal Nature Communications. Lead author Dr Darren Tomlinson says: “The RAS protein is referred to as the ‘Death Star’ – and for good reason. It’s spherical and impenetrable, essentially preventing drugs from binding to it and inhibiting its activity.” Using Leeds’s own patented ‘Affimer’ technology, the team has identified a chink in the Death Star’s armour to allow treatment to take place.

Co-author, PhD student Amy Turner says: “RAS really is the Holy Grail of therapeutic targets. The fact that it has previously been termed ‘undruggable’ has allowed us to demonstrate the huge impact our technology can have. This discovery opens the door for the development of new treatments for a range of deadly cancers.”

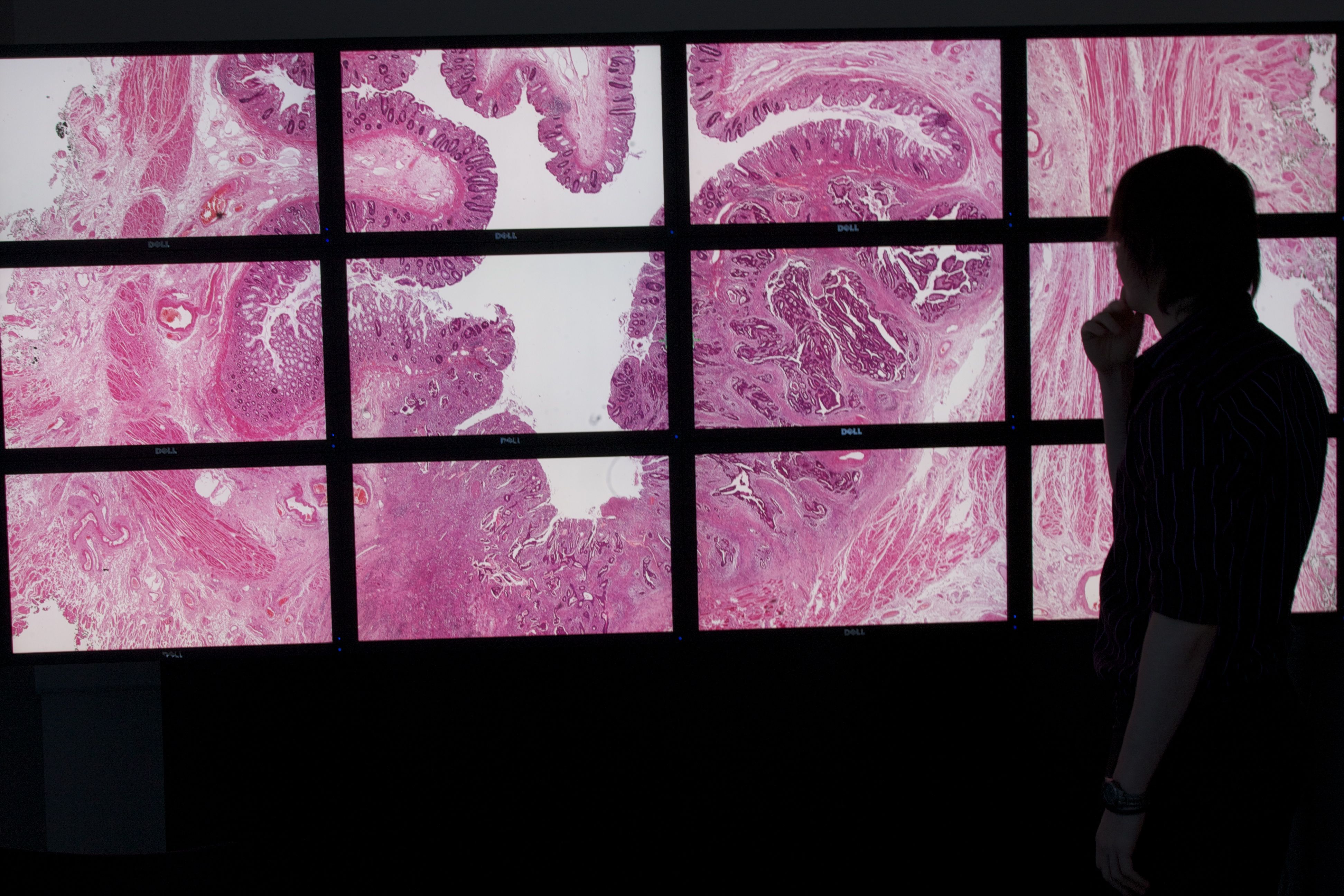

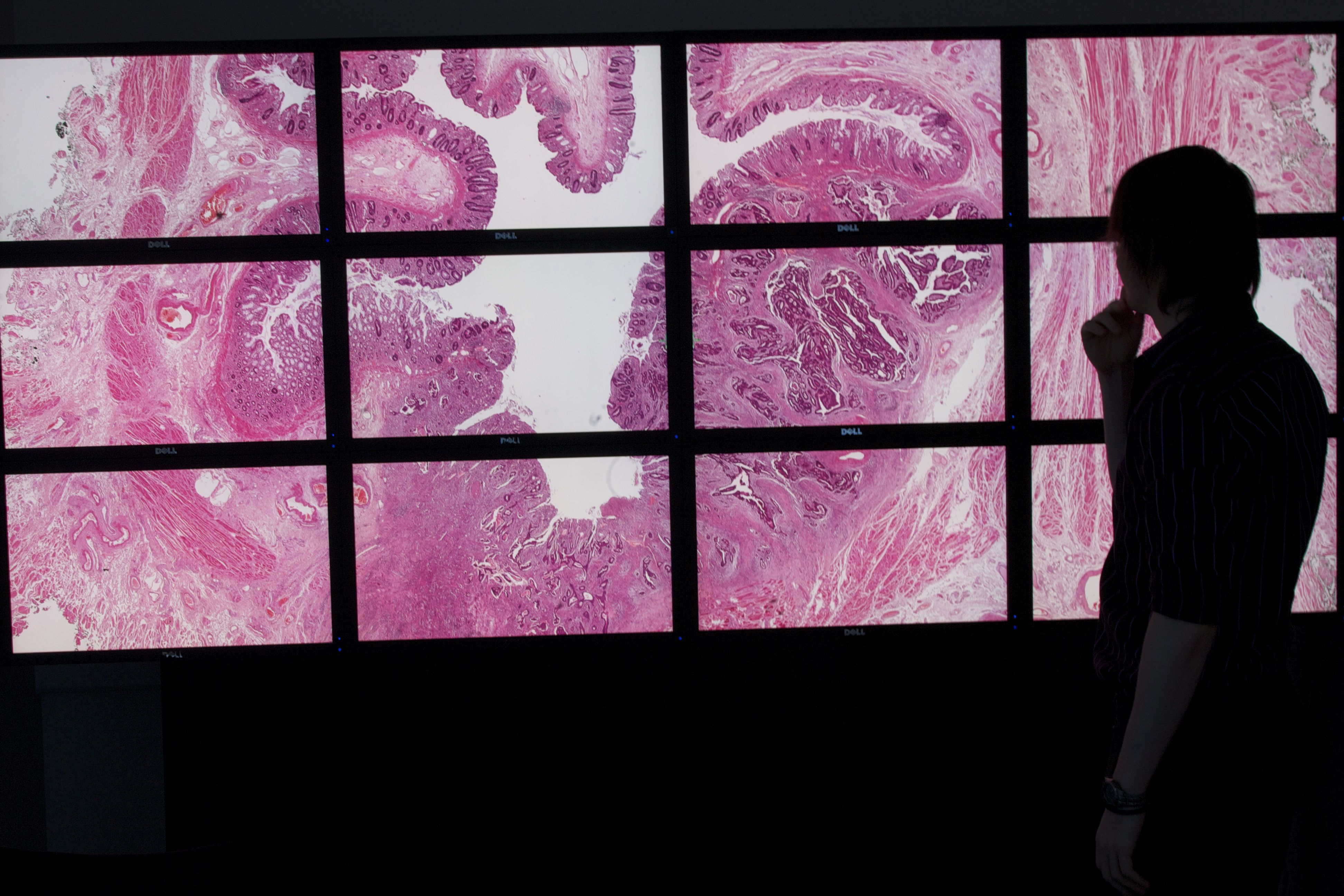

Improving bowel cancer screening

A world-leading team of researchers has discovered that a common type of bacteria found in our guts could contribute to bowel cancer.

Bowel cancer is diagnosed in 1.9 million patients across the globe each year, and it’s the UK’s second biggest cause of cancer death. Professor Phil Quirke and researchers in Leeds are collaborating with an international team of scientists from the UK, Canada, US, Netherlands and Spain. The £20 million “Grand Challenge” project, funded by Cancer Research UK, is investigating how billions of microorganisms impact on cancer risk, development and treatment.

The team has shown that a piece of genetic code found in the common bacteria E. coli can damage human DNA in a gene fundamental to the development of bowel cancer. They have also identified 15 different types of bacteria that are associated with bowel cancer – and shown that these are found in patients with colorectal cancer all over the world, despite different diets and lifestyles.

Phil explains: “Our findings indicate that the microbiome is not only capable of initiating bowel cancer but could also be used to provide a more effective bowel cancer screening test, replacing the current approach that relies on the presence of microscopic blood as an indicator of disease. This would allow us to more accurately identify people who need a colonoscopy, and those who could be spared an unnecessary invasive investigation.”

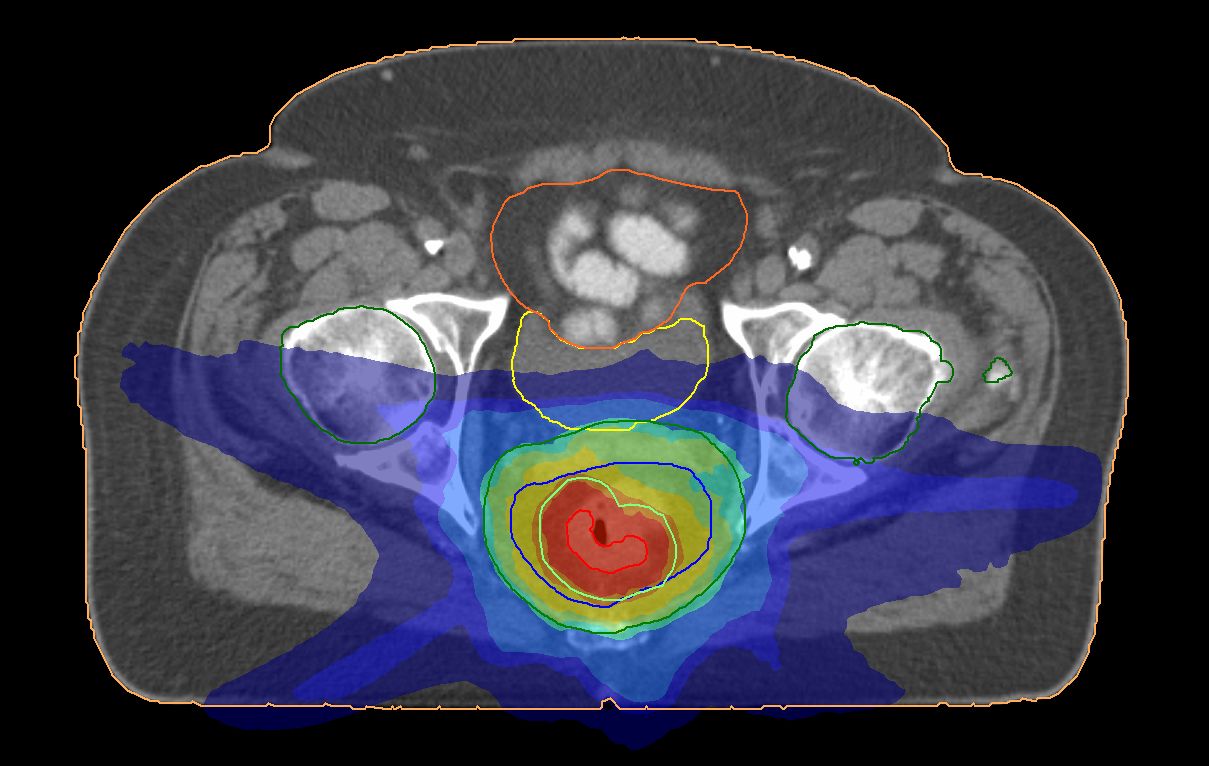

The role of radiotherapy

We have shown how rectal cancer can be treated with radiotherapy to avoid major surgery and improve quality of life.

In the UK, 11,500 people are diagnosed each year with a tumour in the rectum, the lowest part of the bowel. For these patients, surgery is a major undertaking and often requires the fitting of a temporary or permanent stoma bag.

With colleagues at the University of Birmingham, Leeds researchers Dr Alexandra Gilbert and Professor David Sebag-Montefiore led a clinical trial

to test a pioneering approach using precisely targeted radiotherapy followed by local keyhole surgery to remove the cancer. In this Cancer Research UK funded study, 27 patients received the radiotherapy-based approach and 28 underwent major surgery. When radiotherapy was used, 70 per cent of patients were free of cancer after five years and avoided major surgery.

“We were excited to find that so many patients could avoid major surgery and a stoma bag,” says Alexandra. “They had better quality of life than those who had major surgery and became stronger and regained their social lives much more quickly.”

Leeds was recently funded by Cancer Research UK as a Centre of Excellence for Radiotherapy Research and is now leading a larger study to examine treating rectal cancer through radiotherapy alone. “If we demonstrate that rectal cancer can be treated without even keyhole surgery, this would be life-changing for patients worldwide,” says David.

Find out more about how you can help support ground-breaking research at Leeds.

What did you think?