Leeds in the second world war

What was student life like at Leeds during the second world war? In 2008, we gathered memories from some of the people who experienced it.

The moment war was declared we expected to be bombed,” says Leeds native Jack Hartley (Geology 1941). “My father, my mother and I went and sat on the cellar steps that night…”

People expected the sky to be black with German bombers. The government ordered theatres and cinemas to close immediately. But … nothing happened. September 3, 1939, marked only the start of the Phoney War. While an uneasy quiet continued until the following spring, the government gathered its resources, everything reopened and, pro tem, students plunged into life at the University of Leeds with their normal enthusiasm.

“I worked so hard getting there – girls didn’t go to university much then,” says Anita Woolman (Social Studies 1942), who also grew up in Leeds. “And then I went crackers! It was heaven! I was spreading my wings – although I had to put them away and be home by 10.30 because my parents said so.”

Air raids

When the real war did come calling, it wasn’t anything like the blitzes endured elsewhere. But, for a year from summer 1940, Leeds suffered nine raids causing about 70 deaths (perhaps the city was relatively neglected because of the absence of much war-related industry).

Directions to the Air Raid Precautions Shelter on the old Mining/Fine Art building, unnoticed today – and mainly ignored during the war as the University suffered no significant hits. Firewatcher Jack Hartley remembers tackling occasional incendiaries with a stirrup pump and a bucket of water, “But they never went off.”

Directions to the Air Raid Precautions Shelter on the old Mining/Fine Art building, unnoticed today – and mainly ignored during the war as the University suffered no significant hits. Firewatcher Jack Hartley remembers tackling occasional incendiaries with a stirrup pump and a bucket of water, “But they never went off.”

Few felt the direct impact of these sporadic attacks. But one of them was Betty Cox (Botany and Zoology 1946). In bed at home when the house five doors up was destroyed, she was saved by the brown paper that people stuck to their windows to avoid injury from flying glass. However, two air-raid wardens standing across the road were killed.

Then there were the weeks in May and June, 1940, when the soldiers returned from the “little ships” Dunkirk evacuation. “I remember them sitting around in the city centre by the railway station, very bedraggled, mud on their boots,” says Jim McMillan (Physics 1941). “That brought it home to me.”

The war effort

Fortunately for Leeds, the bombing stopped. But the grind of war had barely begun. The blackout every night for the duration; no streetlights or neon signs, black curtains on every window, car headlights reduced to a pencil beam. Almost everything rationed – food, clothing, you could even add “academics” to a special student list of shortages as government often summoned specialists to “the war effort”. On campus, priorities changed.

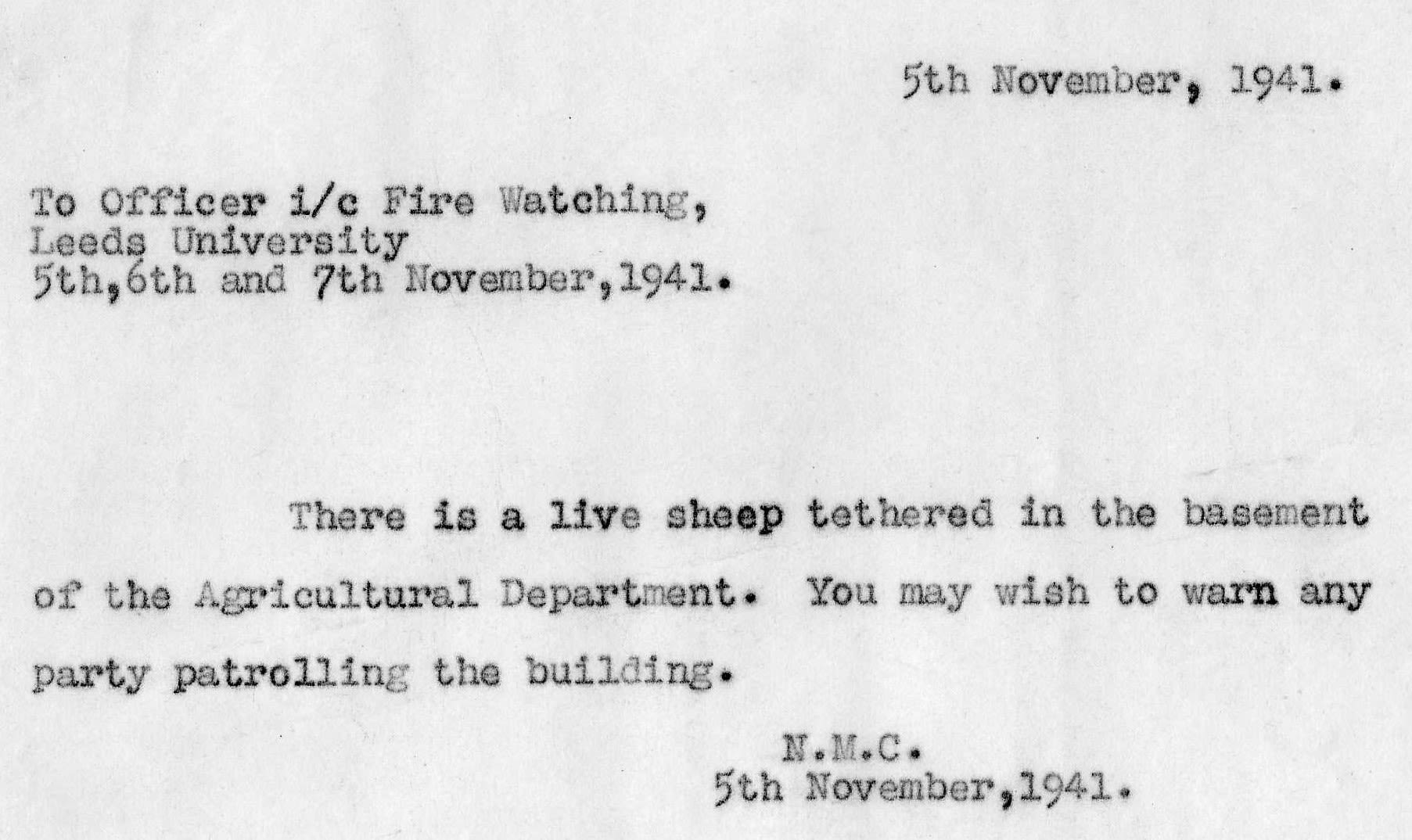

“There is a live sheep tethered in the basement of the Agricultural Department,” wrote the laconically-initialled N.M.C. to “Officer i/c Fire Watching” on November 5, 1941, adding, “You may wish to warn any party patrolling the building.” No doubt. You could get a nasty shock bumping into a sheep in a basement at the dead of night.

The animal must have been a temptation, given that rationing, introduced on January 8, 1940, allowed only a pound or so of meat per week per person. These privations hit everybody – even the rich being restricted by a legal limit of five shillings on the price of a restaurant meal.

Rationing begins

A largely teenaged student body of growing lads and lasses had to make do with allocations such as a weekly four ounces of bacon or one ounce of cheese. The Student Union and halls of residence did their best to provide.

In the Refectory, as Edmund Mallett (Physics 1944) recalled, their hectic 700 lunches a day often featured “terrible” concoctions of powdered egg and powdered milk. Still, what with sugar rationed and “the making and selling of iced cakes” actually illegal, it’s since become a truism that the British were very healthy during the second world war.

Students living at home or in digs with big families counted themselves lucky because there was more to share. “It was worth walking back to the Brudenells for a midday meal with the family I stayed with who had seven kids,” says Jim McMillan. “Meat and two veg every day – and there was high tea and then we were expected down in their living room for a bit of supper about 9 o’clock.”

We’d stain our legs with potassium permanganate and draw a line up the back with an eyebrow pencil for the seam.

“Anyone can understand the deprivation arising from rationing of food, clothes and confectionery and the black-out," says Ken Wetherell (Mining 1945), "but it was felt seriously in all aspects of life, particularly travel. There was a shortage of petrol so only doctors, police and special services used cars.

"Buses were not common. At term end I regularly cycled from Leeds to Guisborough with all my baggage; a hard grind over the Cleveland Hills but the roads were empty. So the only travel resource over longer distances was the train. Trains were crowded with military or naval personnel travelling to their units; corridors were packed with bodies, kit bags and duffel bags; unbelievable congestion and compression; timetables meant nothing. The rail companies were then private, but during the war years they were not allowed to increase fares nor, as far as I could see, invest in the necessary rolling stock.”

With clothing shortages, some people were frustrated by the standard issue “utility” clothes. Anita Woolman says the black market was strictly for “people who didn’t have any morality” but recalls racing downtown when word spread of a batch of legitimate shoes arriving. Betty Cox remembers craftily getting round the lack of nylon stockings, saying: “For dances we’d stain our legs with potassium permanganate and draw a line up the back with an eyebrow pencil for the seam."

Running the University

University administrators faced new challenges beyond the immense logistics of organising national service duties and opening up labs for military research. Decontamination buildings for gas attacks had to be constructed, student military training greatly damaged areas of campus, the Library’s invaluable books needed storing safely – and their transport to Aberystwyth arranging.

Supplies and staff shortages were the norm. Even the Vice-Chancellor’s desk sat empty for six months when Bernard Mouat Jones, an expert in identifying gases, was called upon for military research.

Graduation, January 1946. Like many others, Betty Cox (second from right) graduated early. Terms had been lengthened and coursework condensed “to get the men through to the Forces quicker”.

Graduation, January 1946. Like many others, Betty Cox (second from right) graduated early. Terms had been lengthened and coursework condensed “to get the men through to the Forces quicker”.

The demand for available young graduates was so high that some departments were ordered to condense course work into longer terms, pushing graduation forward by half a year. This, Professor Norman M Comber (he of the tethered sheep warning) could have arranged in his Agriculture department, had there been anyone available to teach.

But his lecturers had all been summoned away to advise Yorkshire farmers on how best to feed the nation. Students complained, and in April 1943, an exasperated Comber wrote to a government official: “It is utterly impossible to carry on an agricultural course without agriculturalists.”

On he moved to the next of an endless list of tasks – completing countless forms for extra towels to replace those made threadbare by 15 years of animal husbandry work. Request, of course, denied.

Funding crisis

For students, their chief restriction was sheer poverty. One after another, wartime graduates from diverse backgrounds who’d all got by on meagre scholarships, not grants, told Leeds they had to count every penny. They could barely afford the price of a pint – “it was a deadly sin,” says Jim McMillan, whose father was a postman in Todmorden on £3 a week. “Not the drink, but spending the money. It was a very narrow, penny-pinching existence.” Ken Wetherell, whose father was a steel moulder, adds: “I could barely afford a cup of coffee. Smoking was totally out of the question too.”

Although the Old Bar opened after hostilities began, none of the alumni recall getting an alcoholic drink there for the duration. Apparently, the Union offered only tea and coffee.

Although the Old Bar opened after hostilities began, none of the alumni recall getting an alcoholic drink there for the duration. Apparently, the Union offered only tea and coffee.

If that momentarily sounds like the competitive misery of Cleese and company’s four Yorkshiremen, it’s misleading. The students’ penury was clearly a practical matter, but not an attitude.

Student fun

In the spirit of the times, they made their own entertainment. Every weekday lunchtime they had a hop in the Riley Smith Hall – 1d to dance to Glenn Miller or Harry Roy on the Panatrope (an early record player). Ken Wetherell delights in recalling how he did the tango to every record because, for complicated reasons, that was all he knew.

And then there were Saturday dances with a student band at the Union, or lunchtime drama society plays, or a 6d variety night at the Leeds Empire, or freebies for the Northern Philharmonic if you volunteered as an usher.

At Devonshire Hall, the warden Commander Evans strove for order. Beyond his view, Leslie Sands (English 1943) terminated a female staff member’s habit of entering students’ rooms without knocking by waiting patiently for her next unannounced entrance and greeting her stark naked. The Hall's rules demanded that girls be out of students’ rooms before dinner and, as Peter Vallow notes, his now wife Rachel (Medicine 1950) was one of those “out at 7” girls, “usually!”

Devonshire's formal evening dinner had its comic aspect as young men in blazers and ties strove for refinement over a banquet of Spam and tapioca pudding – though Ken Wetherell recalls the evening consolation of a special treat: “Each room had a two-bar electric fire which could be laid on its back to boil water for mugs of hot chocolate”.

Future approaches

However, this Rag picture, probably from 1940, is a reminder of the times ahead. Leslie Sands, later a renowned actor in Z Cars, bet his pal Oliver Snow (French 1944) a shilling he wouldn’t run round Headingley wearing only a loin cloth – plus a University tie and a tin hat. Peering over Snow’s right shoulder is their friend James “Harold” Botham (English 1941), who later trained as an RAF pilot. On March 3, 1944, Flight Lieutenant Botham, 23, died when his Halifax bomber was shot down near Ancona, Italy.

Wartime gave every day an undertow of urgency – as Francis West (History 1947) puts it, “There was always the idea that this was a year which might never come again”.

Relationships

Such unspoken intimations of mortality can only have intensified the tight reined passions of boy-girl relationships during that still rather strait-laced era. Most students had emerged with a degree of sexual awkwardness from single-gender schools to arrive at a co-ed university with a male/female imbalance of perhaps 10-1.

Scarcity value had its effects. “I never got any peace!” laughs Anita Woolman. “If I went to the library in the bowels of the earth I was followed. It was hectic, should I say.” Accordingly protective and/or officious, wardens of women’s halls of residence, Oxley and Weetwood, came up with strict rules such as “no men in students’ rooms without a chaperone” and “no red light bulbs to be installed because they inflame men’s passions”.

Even so, Francis West, who was 17 when he started at Leeds (like most freshers then), decorously remembers how you might escort a girl back to Oxley on the tram: “You walked her from the end of the line down a long ginnel and that was a popular place to stop and kiss – but that was the limit of it.”

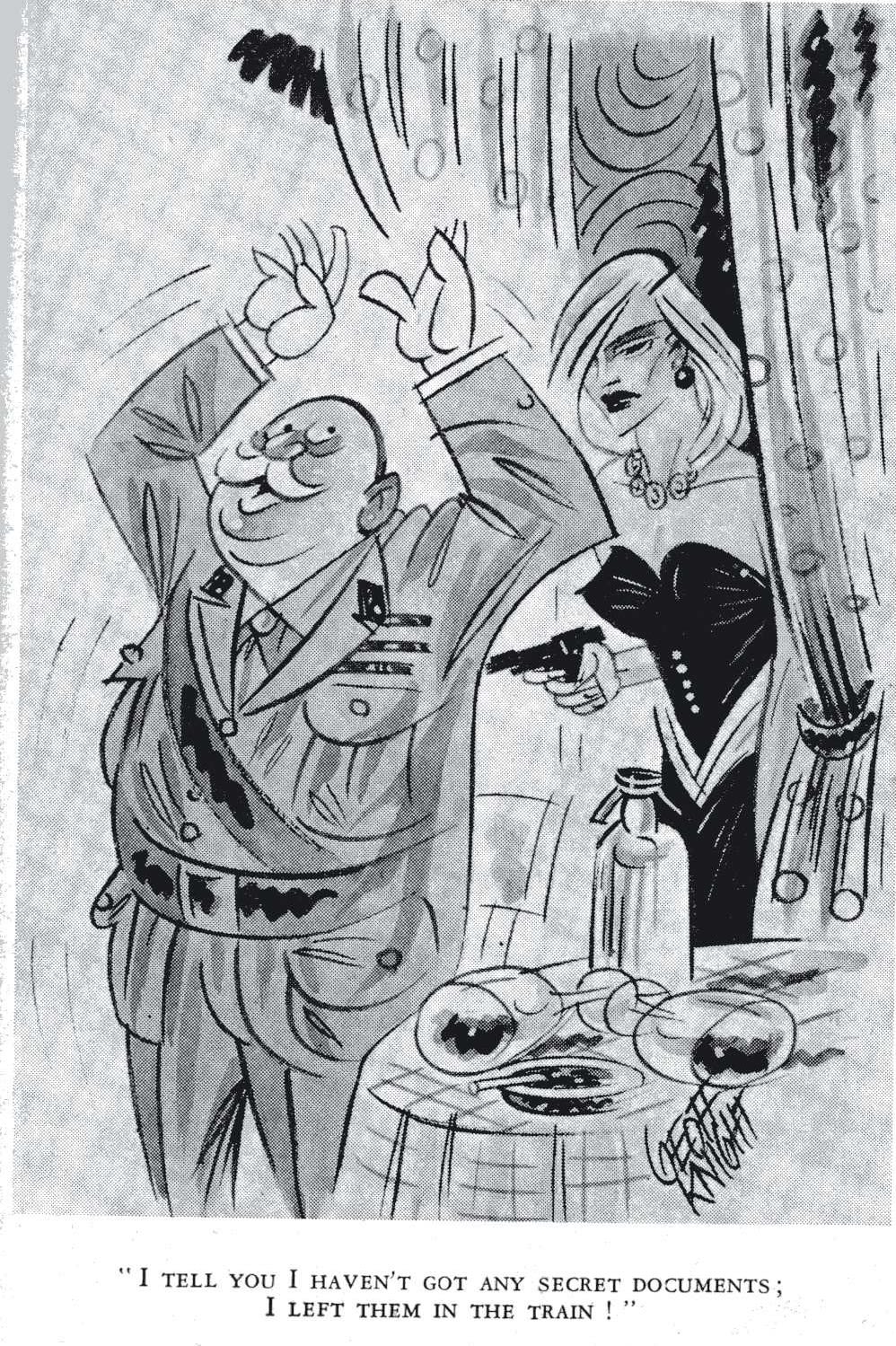

Things don't change. Confidential data leaks merit a 1943 cartoon in the student journal The Gryphon.

Things don't change. Confidential data leaks merit a 1943 cartoon in the student journal The Gryphon.

Common purpose

Still, wartime students had little leisure to languish in romantic reverie. They had to do their bit – and they did it willingly. For the graduates, phrases like “common purpose” and “our byword was service” remained irony-free conversational currency.

Most of the men had regular fire-watch duties, sleeping over on camp beds in the Union basement, the herbarium or someone’s office, then scrambling up onto the roof if the siren sounded. Betty Cox, and others with appropriate training, did “all-night first-aid” shifts – “We got bacon for breakfast which was nice because we didn’t get much normally”. And most women knitted – “gloves for airmen, scarves” – or sewed camouflage netting in a courtyard at the back of the gym.

Military training

Meanwhile, the men geared up for combat. Although the Senior Training Corps and Air Squadron activities on Wednesday afternoons and the odd Saturday had their farcical moments of student blunderings, simulation exercises could be dauntingly realistic. “One of the more unpleasant things was walking through a van filled with teargas – you had to take off your respirator to see what it does to you,” says Francis West. “And we practised an attack once where someone was firing a Bren gun, live rounds. But nowhere near us…”

Fierce army trainers didn’t discourage rumours of a “permitted five per cent casualty rate” or of a young tyro getting a foot blown off – “Some people won’t listen to instructions!” Ken Wetherell underwent two “tough and rigorous” summer weeks of river crossings, live grenades and assault courses at Otley. “The regular sergeants were plainly disgusted with the lackadaisical students”. Francis West adds that wartime prejudice against male students existed beyond hard-bitten veteran circles because “for anybody who had relations in the armed forces there could always be that suspicion of draft dodging.”

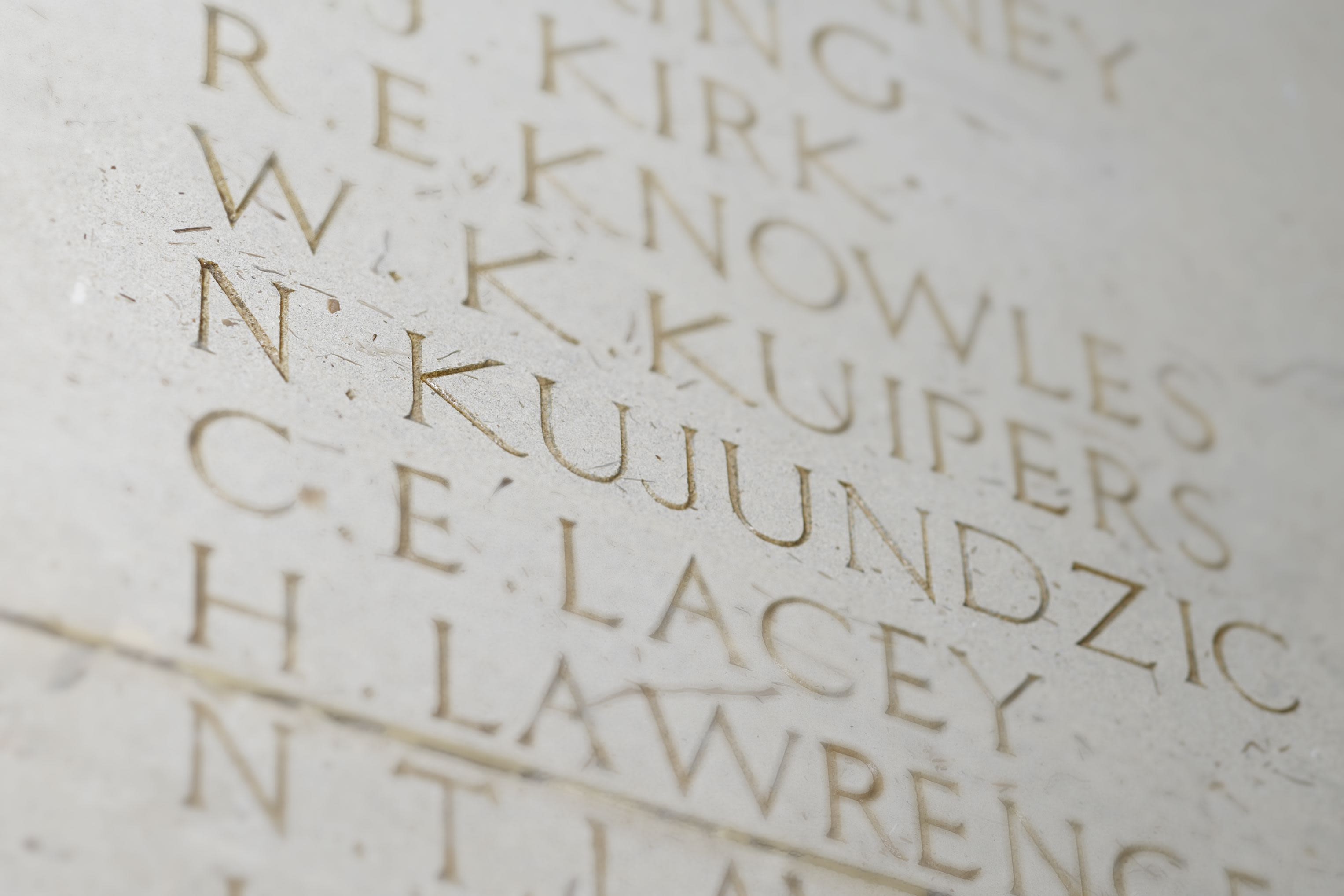

The memorial at the entrance to the Brotherton Library lists 157 former Leeds students who died serving their country in the second world war.

The memorial at the entrance to the Brotherton Library lists 157 former Leeds students who died serving their country in the second world war.

As soon as Peter Vallow (Medicine 1951) started his course in 1942, he found himself drafted into the Senior Training Corps. He describes it as a sort of youth wing of the Home Guard – and life began to resemble Dad's Army, except that the regular army mentor who trained his platoon clearly took an ironic view of the task in hand. This was Company Sergeant Major Brennan, “A smart man with a pronounced Geordie accent, the creases in his trousers knife-edged – in fact, they were sewn in.”

Vallow recounts Brennan’s class on how to get the better of a Panzer: “Now boys,” the Sergeant Major began. “Our first lesson is on the pike - BECAUSE WE HAVE SOME!” A lad commented: “Sergeant Major, we would look proper Charlies, standing there in front of a tank with a pike.” “Not at all, lad,” he replied. “You see, the tank commander would stop and look and say, ‘He is leading us on! There must be guns to the right of us, guns to the left of us, and guns in front of us.’ He’ll shoot you and then turn around and go back.” “But what about me?” cried the student. “You would have done your duty. Sacrificed yourself for your country. We’d be proud of you. Give you a medal, lad!”

Gallows humour in the face of a frightening future. Unless the students had special skills required at home, they did go off to war (as did many women, especially medics).

Jim McMillan well remembers the day in 1941 when student life ended and he set off for four years in army radio signals which took him to Gibraltar and North Africa: “I got up at 5am in Todmorden and travelled to Leeds to catch the same train as the others. I suppose we talked about our fears of what might be coming. I was sort of numb. Not distressed, but obviously we didn’t know what to expect at all.”

It is utterly impossible to carry on an agricultural course without agriculturalists.

Reflections more than 60 years later naturally include doubts and ambiguities. Anita Woolman and Betty Cox both wonder at how little they knew of the war’s realities at the time – given no TV, of course, and censorship of all media. “Unless someone in your family had been called up, in a way you were sheltered at the University,” says Cox. “We were divorced from it,” says Woolman. “We lived a false life. Or rather life went on not at all like in the towns that were severely bombed. But there were trickles of information from German Jews who’d escaped and come here, so I was very much aware what was happening to them.”

Ken Wetherell feels both that the wartime student experience was like being “trapped in a cinema, watching but not taking part” and that amid the cacophony of great events “personal life’s items of achievements and failures went unremarked”.

Celebrations

Still, when there was cause for celebration in these bleak times, students were there. Anita Woolman sang with the University dance band. “I remember the Rag Revue show in December, ’41, at the big cinema in town – I think it was a Paramount then and now it’s a Primark. The medics were raising funds to help the Leeds General Infirmary, and it was full, about 2,000 people. The US had just announced it was coming into the war and at the end of the performance I did a song a few of us had sat down and written the moment we heard the news (sings) ‘America I love you/you are such a good friend to me’. It brought the house down. It was a very emotional time.”

Leeds, like the rest of the country, burst with life when victory in Europe was declared. “That morning I was in a lecture and I put ‘May 8, VE Day’ on top of my notes,” says Betty Cox. In the evening she went to the celebratory dance at the Union. So did Anita Woolman: “It was riotous. A release from anxiety. All the frustrations of war coming out.” Ken Wetherell regrets missing the grand finale because he was laying on his sick-bed too ill to celebrate victory due to preparatory vaccinations for a posting with Shell to Trinidad.

Meanwhile, as a lay resident at the former Anglican priory the Hostel of the Resurrection, Francis West perforce took it more slowly: “There were great parties in the street, of course, but at the Hostel we all went into the chapel and sang the Te Deum – the rejoicing. Afterwards we wandered down into town.”

Set in stone

A statue in Leeds in memory of Flight Sergeant Arthur Aaron VC, DFM, created as a result of a public vote.

A statue in Leeds in memory of Flight Sergeant Arthur Aaron VC, DFM, created as a result of a public vote.

Flight Sergeant Arthur Aaron VC, DFM In March 1941, Arthur Aaron, just 19, joined the “inaugural flight” of the Leeds University Air Squadron while finishing his diploma at Leeds School of Architecture. He enjoyed a short, happy life of training one afternoon a week and ragging rivalry with the earthbound “brown jobs” of the University Officers’ Training Corps. Two years later and already awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal, he flew his 20th operation as a bomber pilot to attack Turin.

Aaron’s Victoria Cross citation records that over Turin, heavy fire hit three engines of Aaron’s Stirling, shattered the windscreen, damaged the controls, killed the navigator, and wounded Aaron in the jaw, lungs and right arm. Aaron was propped up in the pilot’s seat, unable to speak, and writing instructions for the landing with his left hand, having refused pain-killing morphia in order to stay alert.

The flight engineer and bomb aimer took over the controls and headed for North Africa where the bomb aimer landed the plane, wheels up, at Boni airfield at the fifth attempt.

Aaron died nine hours later, after what was described as one of the bravest RAF actions of the war. Flight Lieutenant Arthur Chadwick (Mathematics 1936, Master of Education 1949) was based at Boni at the time and, together with the Intelligence Officer, inspected Aaron’s Stirling after it crash-landed beyond the runway. Aaron was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously.

The Leeds University Air Squadron

The Leeds University Air Squadron

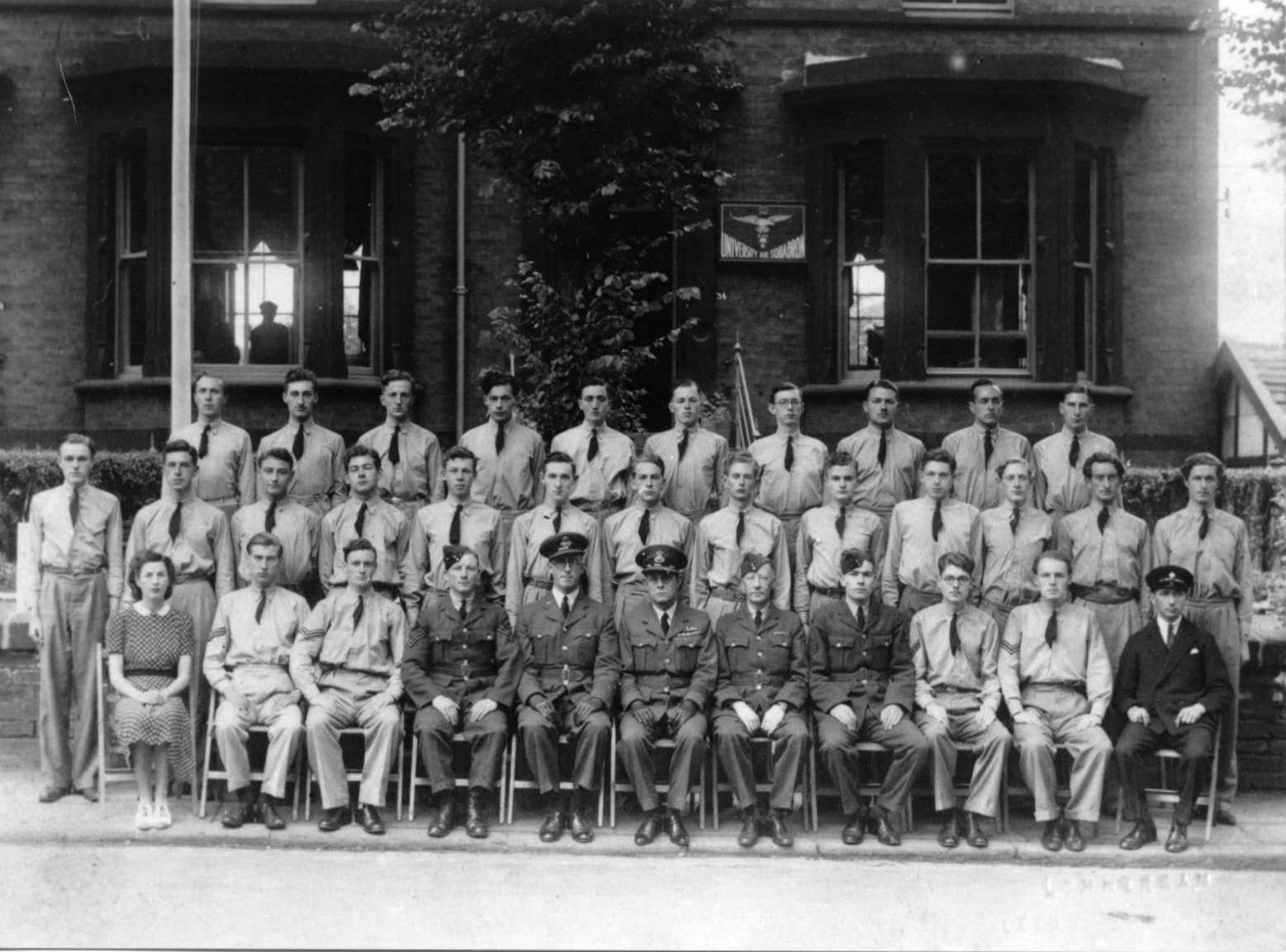

Among the men in this photo of the Leeds University Air Squadron:

• Gordon Appleby (Colour Chemistry 1941, 1947): in the same Turin raid as Aaron, became a flight lieutenant and bomber command pilot. Awarded Distinguished Flying Cross

• Gordon MacDonald Braidwood (Engineering): became a flight lieutenant, Awarded DFC

• Joe Douglas Gartery (History 1941): Missing in action

• Bud Lionel Horner (English 1941, Education Diploma 1945): became a flight lieutenant, navigator in Bomber Command. Awarded DFC

• Neb Kujundzic (Engineering 1941) became a fighter pilot, sacrificed himself to save civilian lives by diverting his burning plane away from Peterborough

• Johnny Whitehead (Sciences): severely injured in action

Of the 19 from the Air Squadron’s A flight who entered the RAF in August to October 1941, 18 successfully completed flying training. Eight are known not to have survived the war:

- Sergeant A Benson

- Flight Lieutenant H Botham

- Flight Lieutenant H K Crowther

- Flight Officer DJ Gartery

- Flight Officer N Kujundzic

- Flight Officer SJ Lupton

- Flight Officer JR Willesden.

With gratitude and in memory of the people mentioned in or who contributed to this article.

Written by Phil Sutcliffe

Please make sure you don't lose your connection to Leeds by updating your details.

Forever Leeds

350,000 alumni

One global community

Never miss a moment. Stay in touch and watch out for our emails.

Update your details