A stitch in time

Trace the bloodline of the University of Leeds, and you find textiles writ large in its DNA.

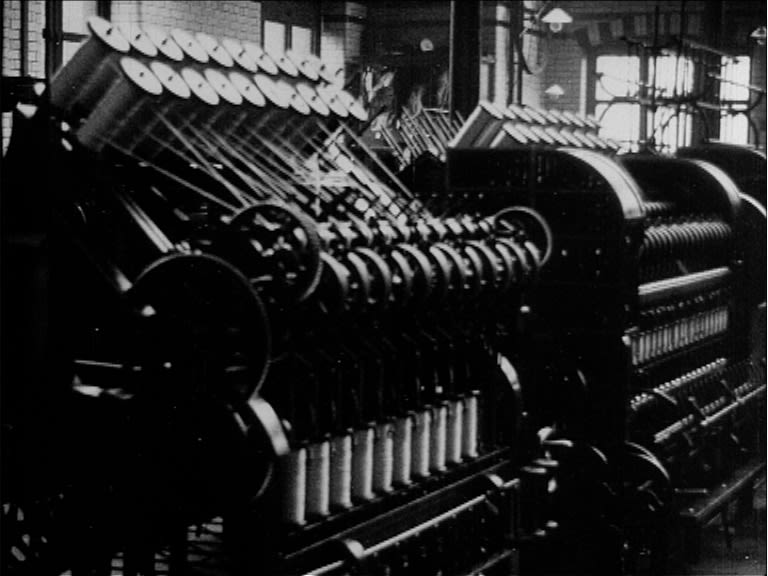

Local industry, keen to harness emerging technologies and develop skilled workers, was critical in establishing the Yorkshire College of Science, one of the Victorian institutions which formed the University. The Clothworkers’ Company funded its first buildings.

Over the next 150 years, a department focused on wool and early man-made fibres evolved into one exploring new materials and responding to the challenges of waste, climate change and our planet’s dwindling resources.

Even so, it remains true to its founding principles – enabling businesses to tackle their challenges and remain competitive, while developing future leaders. Allied to that has been the need to transition away from synthetic fibres made from fossil fuels and back to recycled and bio-based materials, while making sure that textile products on which society depends, still work.

Leeds has responded to the needs of business by opening a new undergraduate BSc course in Textile Innovation and Sustainability, while the relationship with The Clothworkers’ Company continues to flourish. Their multimillion-pound investment to establish the Leeds Institute of Textiles and Colour (LITAC) is the biggest gift they have ever made to the University.

LITAC director Professor Stephen Russell says: “In terms of the global demand for new textile materials and processes, it’s almost like we're going back to the future.”

It’s a beautiful thing to go into a Yorkshire textile factory, built during the industrial revolution, and see how new technology is transforming the design and manufacture of products sold all over the world.

The past

Textiles has been woven into the fabric of the University of Leeds since its earliest days.

For this we perhaps owe a debt to Paris. France’s Exposition Universelle of 1867 – a vast exhibition showcasing invention and innovation from around the world – exposed how Britain’s industrial supremacy was under serious threat. It’s hard to overestimate the importance of textiles to Leeds at the time; by the mid-nineteenth century, the industry employed two fifths of the city’s population.

So concerned by what they had seen in Paris, prominent Leeds woollen manufacturers the Nussey family established a technical school for local workers, recognising that scientific training was key to maintaining a competitive edge against rivals in France, Belgium and Germany.

As a former Mayor of Leeds, Obadiah Nussey was a respected figure. And when automotive engineer James Kitson proposed a college for the training of science teachers and young manufacturers, the two joined forces to petition the Yorkshire Board for Education to establish “a county college for science”.

Though it found favour with other local industrialists, only a third of the required £60,000 had been raised in the first two years. The project may have foundered altogether had Obadiah not secured the support of The Clothworkers’ Company – one of London’s ancient livery companies. The Clothworkers’ gift to establish Department of Textile Industries underpinned the new college, which opened in 1874. Their generosity to the University continues to this day.

Soon the Clothworkers were making more gifts: a lectureship exploring the use of colour in textile design and a Department of Dyeing and Tinctorial Chemistry. These departments became founding academic disciplines of the University of Leeds in 1904, and in the years that followed, Leeds was widely recognised as world-leading in the fields of colour science and textiles.

Its work had still wider scientific importance. In the 1920s and 30s, Lecturer in Textile Physics William Astbury used keratin and collagen fibres to develop the technique of X-ray diffraction of biomolecules. His work laid the foundations for the emerging field of molecular biology and was an important step in the discovery of DNA’s double-helix structure.

The present

150 years on, textiles remain an important and distinctive feature of our University, as the work tackles the pressing issues of a global industry under increasing environmental scrutiny.

Sustainability is a key driver in most of these activities – exemplified by the Future Fashion Factory, a £6.1m collaborative research and development partnership that explores new technologies to boost the design of high-value creative products, to foster shorter product development and design lead times, as well as increase industrial competitiveness, productivity and establish sustainable circular economies.

“Working with industry, we’re providing leadership on how we should design and manufacture textile products for the 21st Century,” says Stephen Russell. “It’s about developing renewable materials for fibres and innovative recycling methods, as well exploring digitalisation, artificial intelligence and other technologies to transform design and manufacturing processes, helping businesses to produce high quality textile products economically and sustainably.”

And with 300 tonnes of textile waste sent to UK landfill or incineration sites every year, and growing concerns about fibres and microplastics leaking into the environment, we are also designing textiles for the end of life – by building options for reuse or recycling into the design from the outset.

Just as our work 150 years ago was responding to the needs of industry, Future Fashion Factory remains focused on the challenges faced by over 550 industrial partners, which includes SMEs and start-ups as well as PLCs.

Some are based in Yorkshire, where textiles remain an important part of the economy: “There is a long-established cluster of SMEs in this region manufacturing very high quality woven fabrics, which find their way into global luxury brand products sold by companies like Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior,” says Stephen. “International buyers appreciate the provenance, quality and heritage of these fabrics. Take a company like Burberry – it’s an international luxury brand, with large weaving and garment manufacturing infrastructure all based in Yorkshire.”

From its factory in Pudsey, another key partner, AW Hainsworth, supplies high value fabrics to major fashion brands, and for interior contract furnishings and personal protective equipment, and supplied the fabric for the guardsmen’s scarlet tunics for the coronation in May. Other local firms provide high performance technical textiles for the aerospace, automotive, medical and defence industries, where science and engineering coupled with design are fundamental to their value. “Textile manufacturers are the engine room of so many products we take for granted,” says Stephen.

Our Clothworkers’ Centre for Textile Materials Innovation for Healthcare is developing fibres and fabrics to sense and respond to health conditions, and materials to assist the repair and regeneration of damaged soft tissues in areas such as chronic wound care and dental surgery. The growing breadth of applications for textiles is reflected in work on composites with embedded electronics for sensing, condition monitoring and energy harvesting.

The Clothworkers’ buildings, which once shook with the rumble of Victorian machinery, now gently thrum with the click and hum of digital instruments and 3D weaving.

Globally, fashion and textiles is a £2 trillion industry employing 430 million people.

But it is also one of the most polluting, estimated to be responsible for up to eight per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and creating almost 100 million tonnes of waste every year.

Established jointly by The Clothworkers’ Company and the University, the Leeds Institute of Textiles and Colour (LITAC) combines multi-disciplinary academic expertise in design, technology, science and engineering to tackle important research challenges across textiles, colour and fashion.

The future

“Globally, the greatest challenges facing the industry are its environmental impacts and the need to operate within planetary boundaries, including meeting net zero targets,” says Stephen.

“How can the industry move away from extracting non-renewable, fossil-based resources? How can we break the cycle of ‘take-make-and-dispose' and establish viable circular economies, including development of new recycling technologies? How can we address over-production, and develop a zero-waste industry? How can we harness digital technology to design new, less environmentally impactful products? How can we enable informed decision-making, and positive behaviour change across the entire ecosystem, to incentivise and accelerate sustainable development?

These are among the questions that we intend to tackle through our planned sustainable textiles research accelerator. Through the support of our donors, we hope a series of research projects over five years will deliver the innovations to enable the transition to a circular economy in textiles. It will develop new renewable materials and fibres, digital tools, fibre processing and production processes, as well as innovative recycling techniques. Between them, these innovations will provide the key tools to enable the global fashion and textiles industry to significantly minimise its environmental impact, reducing our need to extract new raw materials, ensuring far more is re-used and recycled – and significantly reducing waste.

“From the 1950s, consumers fell in love with fossil-based fibres such as polyester that now dominate overall fibre consumption. These have attractive economic and physical properties, but environmental issues have arisen because of their leakage into the environment coupled with low rates of recycling.

“We’re also looking at the viability of a new generation of bio-based materials – fibres made from plant and food waste rather than oil, with the potential to sequester carbon dioxide in their production. However, we still need to make sure they have competitive physical properties and can be recycled.”

Our work in haptic technology plays to the same theme. “If you’re a textile producer in Leeds and you have a customer on the other side of the world, you’d generally have to make lots of physical samples to support the decision-making process, which is a big cost in time and resources. So, my colleagues are working with local companies to develop devices for quantifying and reproducing the tactile properties of fabrics, so a customer can ‘feel’ a fabric remotely. It will speed up decision-making and create far less waste.”

At the same time, a new BSc degree course in Textile Innovation and Sustainability will create a new cohort of bright, passionate individuals equipped to tackle the challenges of an industry facing impetus for change. “We were approached by industry to address a major skills gap in textile technology, so with the help of UKFT we co-designed the new programme,” says Stephen. “Across the industry and in retail, there’s a high demand for textile technologists, but the skilled workforce is ageing, and recruitment is challenging. Companies need people with the technical know-how to drive innovation and sustainable development.

“We are responding to the needs of industry, just as we did 150 years ago. It really feels like things have come full circle.”