THE DAY MUSIC CHANGED THE WORLD?

To mark Live Aid’s 40th anniversary, here’s a Leeds alumni magazine feature from 2010. We learn how Leeds alumni played key roles in helping to galvanise the world’s approach to aid.

In memory of Pete Smith and Lionel Cliffe who contributed to this feature.

THE CONCERT

On October 23, 1984, BBC TV News broadcast Michael Buerk’s first report from the Korem refugee camp, Ethiopia, where tens of thousands of starving people gathered and a hundred died every day.

Bob Geldof watched, decided the only thing he couldn’t do was nothing and launched Band Aid.

Less famously, Pete Smith (Sociology 1974) watched the same bulletin. “Babies dying in front of the cameras… Everybody was too shocked to cry.” It never crossed his mind that he was about to play a central role in the greatest global music show ever.

Post-Leeds, the former Ents Sec had worked successfully as a manager (The Kinks, The Chieftains) and tour manager so, in mid-March, 1985, it was not out of the blue for top promoter Harvey Goldsmith to summon Pete to a meeting. But the subject floored him: Live Aid.

Goldsmith needed an “event co-ordinator”, independently employed by the Band Aid charity (£250 a week, their only paid worker) to guard against vested interests — namely, the BBC which would broadcast the concert, and Band Aid board member Goldsmith who routinely promoted tours for many of the possible performers. Pete accepted and Goldsmith cordially told him “Don’t bother me, get on with it!”

He got stuck into firming up the bill with a one-page, no-fee, no-nonsense contract for performers. As bankable names like Sting, Dire Straits and Queen “committed”, widespread hesitancy was replaced by queues of suddenly altruistic managers asking Pete, “Why can’t my artist play?” — followed by haggles aplenty about where in the line-up said star might appear.

Among several triumphs of hard-nosed diplomacy, Pete recalls levering Paul Weller out of a promised opening spot because Geldof insisted that Status Quo had to start with Rockin’ All Over The World, and, on a US visit, persuading Madonna’s manager that 4pm (Philadelphia) was perfection globally because it gave her prime-time television in Europe and breakfast in Australasia.

Apart from management placation, Pete took care of “logistics” too. He organised the backstage catering, helicopters from Battersea to Wembley and back, buses for artist transport, backstage sleeping arrangements for the crew and … a piano tuner. Everyone did it for expenses, but most chose not to send them in — and Bruce Springsteen covered the cost of leaving his stage up at Wembley from the previous week.

As Pete proudly recollects, “We lived in a world of trust and professionalism”.

But on July 13, 1985, Andy Kershaw still felt like an amateur. Not long out of Leeds (Ents Sec and Political Studies non-graduate 1981, DMus 2005) and a stint roadie-ing for Billy Bragg, he found himself addressing untold millions around the world because he’d recently joined the team of presenters on Whistle Test, who were given the Live Aid job.

The presenters made it up as we went along.

From a sweltering Wembley Stadium commentary box, the presenters “made it up as we went along”. Andy had no trouble with the Africa/politics interviews. What nearly undid him, not being a cinemagoer, was John Hurt. “Who is he?” he muttered to the director, who mouthed “Actor!” just as the distinguished thespian took his seat. Andy improvised, “Well, John, I wonder what the acting profession might be able to do for Ethiopia?”

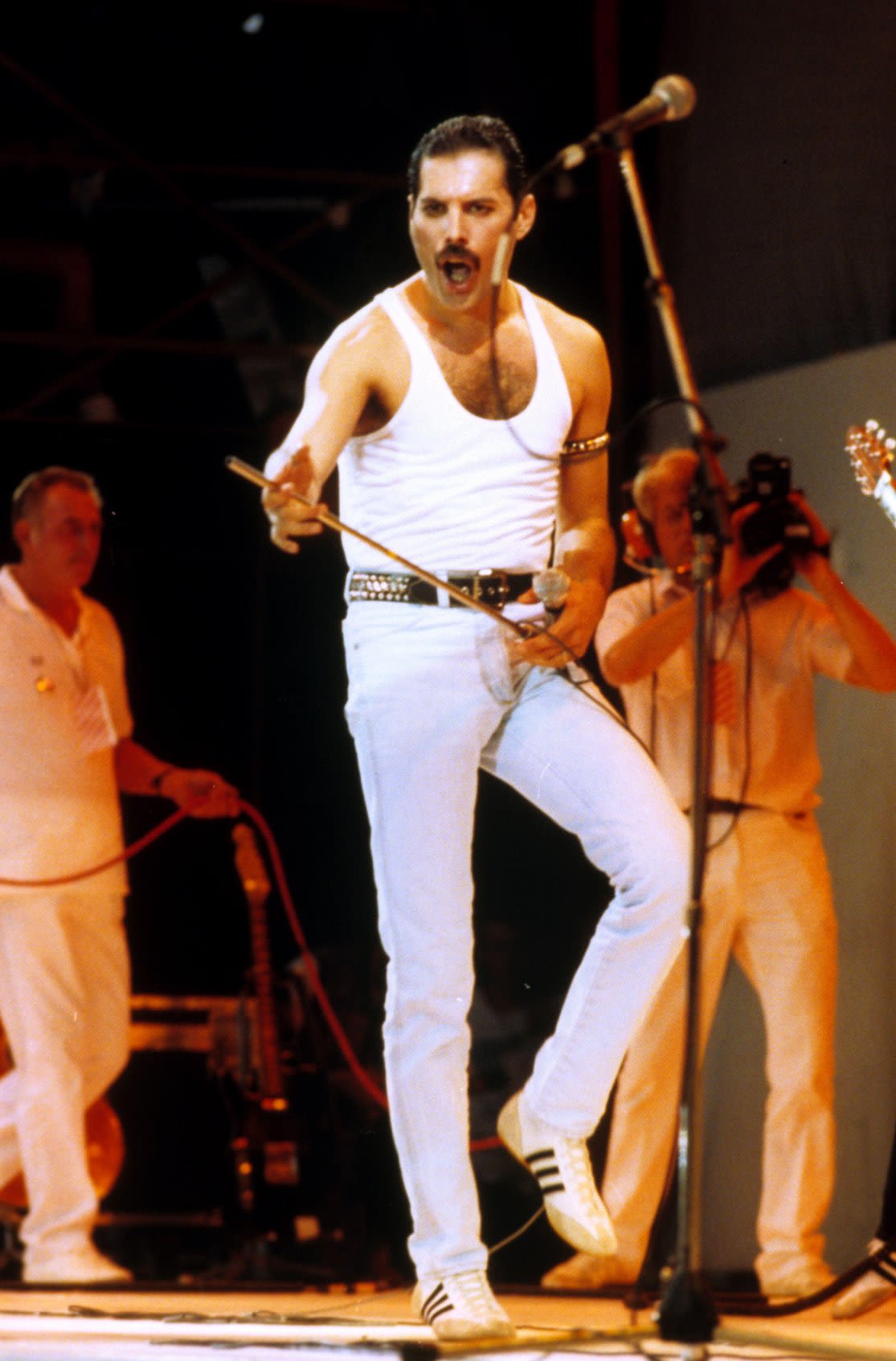

Freddie Mercury captivated the crowd with what became the iconic Live Aid performance

Freddie Mercury captivated the crowd with what became the iconic Live Aid performance

Meanwhile, in the hub-bub backstage, given that “not one artist was late or went missing”, co-ordinator Pete largely enjoyed the day. His performer hero of the event: Elvis Costello. Costello hit the spot with All You Need Is Love and responded to Pete’s apology — he’d been cut from “three songs with band” to “one song solo” — with an unassuming, “Pleased to do my bit”.

Cock-up of the day? The awkward culture clash around Yusuf Islam, formerly Cat Stevens, says Pete. He turned up backstage for a solo spot which would have been his first public performance since 1978. Pete, who’d invited him, introduced him to Geldof and Goldsmith. Yusuf said he would sing a children’s song. Fixed on the notion that the most popular songs would result in more donations from grateful viewers, Geldof said, no, he should do one of his hits. Although Pete argued that Yusuf’s song would be different but appropriate, neither would compromise and Yusef didn’t play.

Meanwhile, Live Aid day’s most brilliant bit of coping, Pete later learned, came from helicopter pilot Jed Hughes and his late-afternoon passenger David Bowie. They were landing at a Wembley cricket club that had allowed their pitch to become a temporary helipad for the day. However, they also had a wedding reception in the pavilion and the families were demanding that Hughes stop flying. He told Bowie who said, “Leave this to me”, walked into the reception, hollered “Sorry to interrupt, but we just wanted to say we’re sorry about the noise…” and had his photograph taken with the bride and groom. Problem solved.

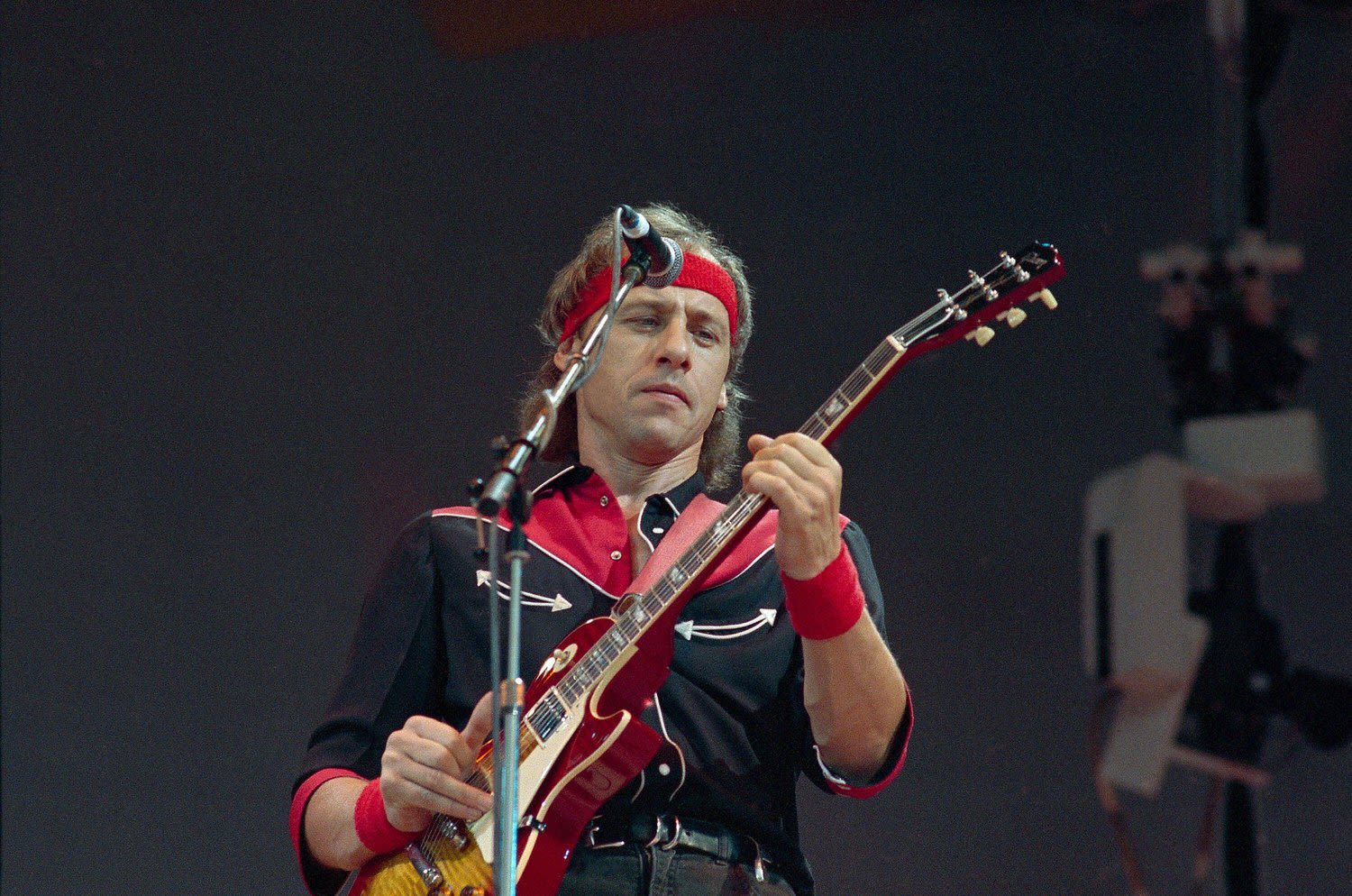

Dire Straits leader Mark Knopfler OBE (English 1973, Honorary DMus 1995) performed at Live Aid

Dire Straits leader Mark Knopfler OBE (English 1973, Honorary DMus 1995) performed at Live Aid

Pete and Andy both took some satisfaction from their parts in raising £100 million which Band Aid then distributed as diligently as possible to feed people and contribute to easing impoverishment long-term. But, naturally, bestriding the globe on the telly while trying to tackle geopolitical catastrophes with pop songs threw up conflicts.

Pete followed, though he had no responsibility for, the unfolding story of why so many major African American artists didn’t appear in Philadelphia. The nub of it, he says, was that ABC TV, which carried a highlights show on the Saturday night, wouldn’t feature them because their advertisers wanted Led Zeppelin, Dylan and such. “The black artists said they weren’t coming unless their status was properly acknowledged on television,” says Pete. “After Michael Jackson’s Thriller, power and market share in the industry was changing hands.” But ABC didn’t get it. Hence the absence of the Jacksons, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross and others.

Twenty years later at Live 8, with the African Americans’ battle won, Andy found himself embroiled because he highlighted the lack of African artists on the UK bill when the whole enterprise was aimed at raising Africa-consciousness immediately before the Gleneagles G8 conference of rich-world leaders. When some African bands were belatedly invited, he says, they featured at the “fringe” event at Cornwall’s Eden Project, not in London or Edinburgh. At which he piled into the debate with a fiery op ed piece in The Independent, arguing that the crux of the issue wasn’t skin colour but culture: “My point wasn’t about black artists, it was about African artists.”

Overall, while Pete accentuates the positive about the whole experience (on Live 8 he helped organise in Philadelphia), he adds: “Organising Live Aid, our morale held up because ‘something was being done’, but I didn’t go with any cant that it was changing the world. I know ultimately governments create famines and governments have to solve them.”

Expert view

Dr Simon Warner, current University of Leeds lecturer on Popular Music, reflects on Live Aid:

“I watched it on TV. The stuff of dreams: an iconic stadium, 70,000 crowd, great artists, a quarter of the Earth tuning in — an audacious attempt to transform rock’s popularity into a force for good and for change. In the end, the fantastic amount of money raised was still a drop in the ocean of Africa’s hunger crisis. It drew the world’s attention to the problem though, and I don’t think politicians could have done that.

“Geldof was astonishing; a minor and fading figure, but through force of will and energy and determination a gobby musician with a fabulous turn of phrase created something magnificent, took on the world, and won. Pop had been a fly-by-night wild child. With Live Aid it became an adult, assuming social responsibility. Since then it’s been used in countless ways to support people in terrible disasters.

“Live 8, in 2005, tried to capture the spirit of Live Aid, but indulgently and sentimentally, which made it feel second-rate. The issues were too complicated — economic, environmental — compared to the inspired appeal to feed the hungry. There was a sense that politicians were riding on a cultural event too.

“Live Aid was a force for good, certainly. A force for change, I’m not sure. But back in 1985 there was an immaculate trade-off for everyone who played — be altruistic saviours of Africa and sell truckloads of records!”

IN ETHIOPIA

“On July 13, 1985, I was at the Acropole Hotel, Khartoum,” recalls journalist Paul Vallely (English and Philosophy 1974). “In the lounge all the aid workers gathered round the telly watching Live Aid. I just felt scornful of bloody pop stars thinking they could solve Africa’s problems.”

But fate — and Bob Geldof — were waiting to change his view.

A junior reporter on The Times, dispatched to Ethiopia in January, 1985, he found he couldn’t stomach the standard press-pack approach: “Most reporters stayed at the Addis Ababa Hilton, flew out to a refugee camp for the day, and filed a famine report before sitting down to steak and a bottle of claret.”

Deciding to look beyond the clichés, he traveled overland with aid workers for a week at a time, building his knowledge of what caused the famine: drought itself, but also the Government’s oppressive regime, its wars with independence movements in Eritrea and Tigray, and the West’s rapacious attitude to trade with Africa.

But he recalls how, after a lot of interviews with impoverished and starving people, one experience opened his eyes: “This woman, Fatima Muhammed, who’d just told me the child she held in her arms was dying, started asking me questions: did I have children, how were they? That brought it home: this was not A Victim Of The Famine, she was a real person with her own life and her own… etiquette.”

He’s not sure whether such insights affected his writing, though “perhaps some of that naiveté and directness did come through”. But when he got home, briefly, a few weeks later — thrown out by the Ethiopian Government — he was astounded to find that Geldof had read his reports and been so impressed that he asked him to come on a journey across Africa to determine how Live Aid’s money could best be spent.

So Paul observed Geldof’s encounters with presidents starstruck by his dishevelled prestige — plus the “£100 million in his back pocket”. Close up, he noted his companion’s trenchant “lack of deference”, especially back in Ethiopia. When immigration refused “enemy of the revolution” Paul entry, Geldof threatened to get straight back on the plane unless they let him in. Then, face-to-face with Mengistu Haile Mariam, chairman of the Derg military junta, Geldof called him “a bloodthirsty ****”.

A beautiful 25-year friendship between Paul and Geldof ensued. Once the Band Aid Trust had disbursed the bulk of the money, Geldof decided he had to earn a living again and Paul ghosted his autobiography, Is That It?

“But Geldof carried on campaigning,” says Paul. “I was an intermittent consultant. In 2004 we went back to Ethiopia. It seemed as bad as ever. Geldof was shocked, so he rang Tony Blair about it and the result was the Commission for Africa (16 assorted politicos, plus Geldof, headed by Blair and Ethiopian PM Meles Zenawi).” With Geldof insisting their report shouldn’t be written by an academic, Paul got the job (he’d long since moved from The Times to The Independent).

The main target for the report’s recommendations on debt cancellation, removing trade barriers to developing-world products, and increasing aid was the G8 conference of the world’s leading economies, set for July 6-8, 2005, at Gleneagles, Scotland. But when it seemed the national leaders had not taken the proposals to heart, Geldof and U2’s Bono launched a deliberate Live Aid follow-up, Live 8 — concerts in each of the G8 countries plus South Africa.

By then Paul was not just an expert journalist but a leading light in development organisations such as Traidcraft. Geldof and Bono took him along as advisor while they lobbied George Bush, Jacques Chirac, Gerhard Schroeder, Tony Blair and others. Hard man/soft man, Geldof the ranter, Bono the charmer, they argued their way from capital to capital.

Opinions on the efficacy and outcomes of Band Aid/Live Aid/Live 8 still vary enormously. Introducing the Live Aid book in 1985, their progenitor and champion Geldof wrote: “If there is a meanness, an empty cynicism, a terrifying selfishness and greed in us, then that day, watching that television, dancing in that crowd, playing on that stage, the obverse of our cruelty was made manifest… Remember on the day you die, there is someone alive in Africa cos one day you watched a pop concert.”

Conversely, Jane Plastow, now director of Leeds University Centre for African Studies, then a teacher in Addis Ababa, experienced Live Aid as an affront to Ethiopians’ culture and history: “Although they were grateful for the outpouring of support, there was great crassness from the West and a distressing need for a feel-good factor among charity givers.”

Ethiopian Bekele Geleta (MA Transport Studies 1974, LLD 2010), now Geneva-based secretary general of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, has mixed feelings. Working for the Ethiopian Red Cross in 1985, he found the concert pained him: “I watched on TV. The audience’s emotion strengthened my belief in humanity. But, deep in me, I felt very bad about Ethiopians being pitied.”

Yet, in retrospect, he recognises substantial long-term benefit: “Live Aid contributed to influencing world public opinion to mobilise a big amount of money, to build global commitment never again to allow loss of human life of that magnitude due to the lack of basic necessities, and to reshape the humanitarian industry with better purpose, vision, discipline, systems, operational preparedness, accountability and transparency.”

For his part, Paul has constantly campaigned for “structural change to usher in a more just system”. But following yet another Ethiopian foray with Geldof in December, 2009, he argues that debt relief and aid have improved “2000 times” on 1985 levels and affirms: “Live Aid raised the consciousness of people in the UK about Africa — that was the main achievement, rather than the money.”

Words: Phil Sutcliffe 2010

Expert view

Dr Lionel Cliffe, then a senior lecturer at Leeds, now emeritus professor of politics, reflects on food insecurity in Ethiopia:

“Live Aid’s 25th anniversary brings back memories, not so much of the concert but of seeing events on the ground for myself,” says Dr Lionel Cliffe.

In 1986, Cliffe spent months in Eritrea, then part of Ethiopia and badly famine-affected, part of a University of Leeds research team commissioned by aid agencies to assess continuing need and trying to clarify the tangled causes of the famine — drought or civil war? He feels Live Aid’s mass humanitarian emotions tended to oversimplify and ignore the political.

On this “quite adventurous trip”, they visited some of the 400 villages surveyed, driving at night over rough terrain to avoid Government spotter planes (bombers could follow). They witnessed the Eritrean and Tigrayan liberation fronts’ impressive relief organisations in the areas they had liberated, getting food through that had been delivered by Inter-Church Aid, Save The Children, Oxfam and Band Aid.

But small personal experiences sometimes overshadowed the systematic fact gathering, about losses of access to land and markets, of animals and livelihoods. For instance, while researching herders’ livestock depletion, they came to a village and the head man said he’d gladly talk, but first he must feed them. “They slaughtered a goat,” Lionel recalls. “The tradition of hospitality meant we ate one of their last animals.”

Today, he points out, even without a drought, 10 per cent of Ethiopia’s 85 million people need food relief. Figures released in October 2010 by the World Bank say 40 percent are under the poverty line. “The World Food Programme calls it ‘structural food insecurity’. This permanent impoverishment has never been adequately addressed. Even now, the Ethiopian government is making over huge tracts of land to companies from the Middle East, India and China to produce bio-fuels; this might help the economy but won’t help the poor.”

LIVE 8

Our magazine feature on Live Aid made passing reference to how “event co-ordinator” Pete Smith, former Leeds Ents Sec and subsequent music biz all-rounder, helped organise Live 8 in Philadelphia.

In contrast to the non-stop four months he put into making Live Aid happen in 1985, his involvement in its successor, 20 years on, was brief and last-minute. He’d had nothing to do with the event until a couple of days in advance when Live Aid/Live 8 UK promoter Harvey Goldsmith got worried about the American end. Remembering that Pete had done some advance troubleshooting in the US back in ’85, Goldsmith rang and said, “I need you in Philadelphia — tomorrow”.

An hour after the plane touched down Pete was asking the American promoter, “What can I do?” “Nothing,” came the reply. “You’re just here to reassure Harvey.”

Wandering about the site — the stage was set up in front of the Museum Of Art at one end of Philadelphia’s ceremonial avenue, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway — he noticed the absence of “clear arrangements” for getting the artists from ‘backstage’, behind the Museum, to the stage. And there was quite a distance involved.

At Live Aid, to keep the artists on schedule, he’d devised a sort of star triage system where they’d be serially helicoptered into the area, parked at Wembley Conference Centre, then bussed over to the Stadium. He devised a similar process for Philadelphia, explaining it in air-travel terms: “Check-in, departure lounge, ground transport — these people know about airports”. And so the likes of Bon Jovi, Kanye West and Stevie Wonder — not to mention, Leeds’ own Kaiser Chiefs — rolled past Rocky’s steps to greet a 1,100,000 live audience plus the world’s TV cameras.

On this occasion, though, Pete felt quite a divide between professional and political satisfaction. “It was a great day,” he says. “But there was a tremendous disconnection between event and intent. Most of the artists had no idea about the cause, the complex geopolitics. In terms of why people wanted to do it, Live Aid was very different, a phenomenal sense of event and community. But at Live 8 I didn’t get.”

However, Paul Vallely feels Live 8 worked usefully in reaching G8 national leaders even if it proved less captivating in mass audience terms. “Live 8’s purpose was to create political leverage and by then Bob was much better aware of how the system worked,” he says. “He went after the civil servants, such as the head of the British diplomatic service, who prepared the conferences for the politicians. He used that contact to get newspaper stories on the table in front of the presidents and prime ministers at the start of meetings.”

Vallely says that, after Geldof had worked on Tony Blair’s Commission for Africa report in 2004-5, Bono persuaded him that G8 leaders weren’t taking its recommendations to heart and that a “new” Live Aid could put public pressure on them. “Then I was involved in lobbying Bush, Chirac and Schroeder,” says Vallely. “We talked to Paul Wolfowitz (President of the World Bank, formerly in Bush’s cabinet), a neocon who had had a Damascus conversion on Africa towards our more interventionist view. Wolfowitz got on to Bush, as did Laura Bush and their daughter. So when Bono met Bush we needed $2 billion for children’s education and AIDS in Africa and we got it — and Bush got his photo opportunity with Bono.”