Leeds in the first world war

The nightmare of the first world war was punctuated by curiosity about Belgians, a toffee tin helping a POW escape and the worst tragedy in the history of Leeds.

Over there was where it started and mostly stayed, but the first world war had hardly drawn breath before it came home to Leeds.

17 September 1914, six weeks after Germany’s invasion of Belgium triggered the British declaration of hostilities, a train arrived at Midland Station, Leeds, bearing 90 wounded men, the first wave of casualties from the Battle of Mons and subsequent Great Retreat.

Ambulances awaited and conveyed them, not straight to hospital as they might have anticipated, but to City Square where stood Lord Mayor Edward Brotherton in full regalia, proffering a formal civic reception. But he was not alone.

Forewarned by the press, Leeds had come out en masse, packing the Square, craning and jostling to view this new phenomenon – casualties of war.

Some of the wounded could walk with sticks or an arm to support them. Many were carried by stretcher-bearers. Some, as the chaplain of Beckett Park Hospital later recalled, had been “entirely covered from view and, of these, some would not have been recognised by those who knew them best.”

“It was exciting and scary at the same time,” wrote Ronald Dalley, a boy scout chosen to drive an ambulance because he’d done his first aid badge. Regardless, the citizenry cheered and threw cigarettes and tobacco at wounded soldiers they glimpsed along the route to the hospital in Headingley.

But that wasn’t all. Within days, a group of Belgian refugees arrived in Leeds and again the mayor donned his chain and robes, said Alison Fell, former Professor of French Cultural History who led the University’s far-reaching Legacies of War project.

“The whole city came out to have a look – they needed police to keep the crowd back.” Looking back, such intense interest may seem strange but, she said: “People had read so much about atrocities committed by German troops in Belgium, especially against women and children, and they felt afraid it could happen here. This was war arriving on the doorstep.”

Cadets of the University of Leeds Officers' Training Corps practice Morse code with battery-powered buzzers.

Cadets of the University of Leeds Officers' Training Corps practice Morse code with battery-powered buzzers.

Back then, town and gown were entwined in a way that may not have been seen since. For instance, a Leeds Medical School alum and Leeds Infirmary surgeon, Dr Joseph Faulkner Dobson, started preparing Beckett Park Hospital for war in 1912. By the time that first contingent of wounded arrived he had 600 beds and 92 nurses ready.

Dobson’s hospital colleague was Sir Berkeley Moynihan, the University’s Professor of Clinical Surgery, who devised new procedures for operating on jaw injuries and served intermittently as a medic on the Western Front – twice mentioned in dispatches – while serving nationally as Chair of the Army’s Medical Advisory Board.

Over the five years of war and its immediate aftermath, the hospital dealt with 57,200 wounded men, of whom only 266 died. Likewise, the University usefully augmented Leeds’ support for the displaced Belgians – 1,500 arrived by Christmas, 1914 – with fundraising coming from students and groups of academics’ wives.

The refugees’ higher educational needs won prompt consideration too, as the University Council voted on 4 November: “Belgian students who know English sufficiently well to enable them to follow lectures” could attend classes fee-free.

However, the University was forced to make one grievous exception to its generosity – in the case of Albert Schüddekopf, Professor of German since 1890. Schüddekopf’s fate rested on the City Council, which provided the University with a modest Education Committee grant. The Aliens Registration Act decreed that Germans of military age living in the UK should be interned (mostly on the Isle of Man) or repatriated – but Professor Schüddekopf was legally safe because he had taken British nationality two years earlier.

But, paying a German’s wages didn’t sit well with the City Council and they pressured the University’s Vice-Chancellor Michael Sadler to remove him. After defending Schüddekopf for as long as possible, Sadler went to his home in Harrogate to deliver the bad news. Schüddekopf, aged 54, died of a stroke two days later. The professor’s son was a Leeds graduate and a doctor with the Leeds Regiment who survived the war. When he came home he changed his name to Shuttleworth.

That personal story reflects the diversity of the University’s involvement, sometimes entanglement, in the war effort via funding from local and national government.

When war was looming, the city fathers took stock. Knowing that Leeds had abundant heavy industry, but hardly any arms factories, they set about rectifying the situation post-haste. They founded the Leeds Munitions Committee, which immediately turned to the University as a crucial ally.

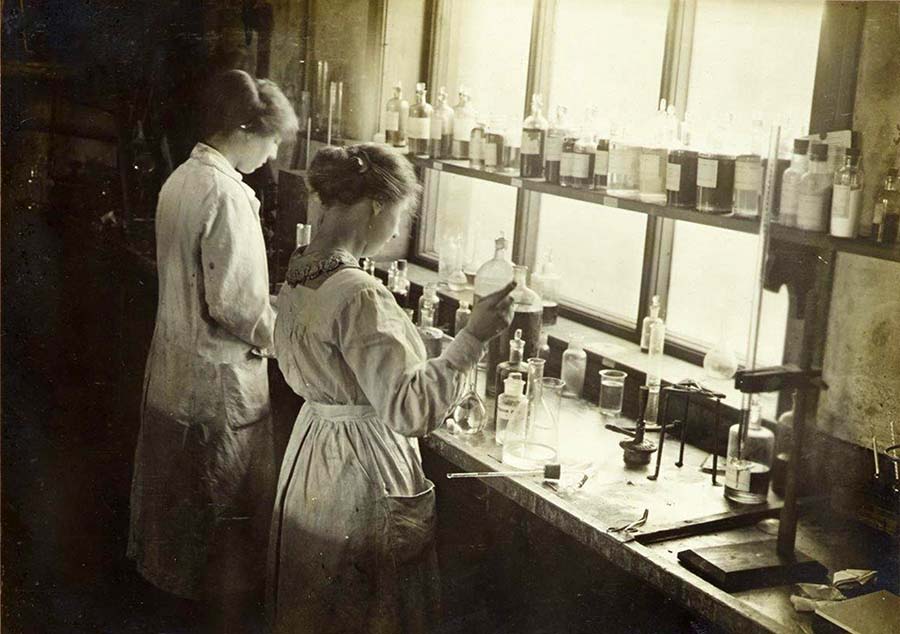

Leeds students doing research at an explosives factory

Leeds students doing research at an explosives factory

Researchers across the University focussed on supporting the country as it dealt with the logistics of sending millions of men to war. The State stepped in to control almost everything and the University cooperated – and was paid to do the work.

One Munitions Committee venture which proved the dynamism – and the hazards – of military-commercial-political-academic collaboration was the Barnbow shell factory in East Leeds. Built from scratch in 1915, at its peak it employed 16,000, more than 90% of them women. “The Barnbow lasses” worked on three shifts round the clock, packing explosives and fuses into howitzer shells.

And the University played its patriotic part. “The University helped to train women as munitions workers. And, meanwhile, its chemists had labs to develop explosives in local factories,” said Professor Fell. “When the Government needed manual workers trained for agriculture – or an armaments factory – they turned to the University because, with its foundation in textiles, it had very close links with industry.”

In 1916, December 5, something went wrong at the Barnbow factory and a massive explosion killed 35 women outright, injuring many more. It’s referred to as the worst tragedy in the history of Leeds in terms of the death toll but, at the time, censorship ensured it passed unreported beyond word of mouth. With wages hitting £12 a week (more than £1,000 at today’s values) work resumed within hours. There was a war on, after all …

Leeds student OTC members learn to care for their feet during combat

Leeds student OTC members learn to care for their feet during combat

Back on campus, departments pitched in. They looked at growing flax for the fabric of early warplanes. They explored electrification of fibres, manufacturing antiseptics, anaesthetics, varnishes for shells, and dyes for uniforms. A spin-off into explosives was successfully pursued by aptly named Tinctorial Chemistry Professor Arthur Green – who later, in Manchester, moved on to the production of Britain’s mercifully little used mustard gas supplies.

The progression of war changed campus life as supplies, students and staff dwindled. In November 1916, a review of a performance in the student newspaper, The Gryphon, noted the change: “the lack of talent, where once there was superabundance, is indicative of the way Leeds University has identified itself with the needs of the war”.

A year later in December 1917, The Gryphon felt the need to assure exam-taking students “on very good authority” that “there will be no shortage of ink, pens and paper”.

Teaching staff disappeared as they were co-opted to the war effort. Chemistry students lost their professor when Arthur Smithells left Leeds to lecture to the camps of the Northern Command before becoming the country’s Chief Chemical Advisor for Anti-Gas Training of the Home Forces. Mr WR Johnson in the Textiles department left to support the analysis of samples and leather for the government.

Captain Arthur Meurig Pryce had been demonstrator in bacteriology before joining the Royal Army Medical Corps early in the war. He served with the 14th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers through the Somme and Ypres, “sticking to his post under terrible fire and worked on, attending the wounded until all around him were either killed or wounded, with the greatest unconcern,” according to a medical colleague.

Commissioned officers formed the majority of the 1,596 staff and students who joined the Forces. Around 85% of the 350-odd killed in battle were captains or lieutenants, usually the highest ranks left in the line when action threatened. About 40 of the dead had gone straight from Leeds studies to combat.

The University’s alumni also played their part, like Lieutenant Alexander Rosamond, who had been the first resident student at Lyddon Hall, and former captain of the University football team. He was killed leading his company into action in September 1915.

Leeds OTC cadets in training on the University campus

Leeds OTC cadets in training on the University campus

Most of the University students were members of the University's Officer Training Corps (OTC), to which they were expected to devote 15 hours a week for training. Upon request from the War Office, the University found extra sleeping space and more Refectory meals for them when the OTC increased from 50 to 100 officers.

The OTC switched almost overnight from a lark with an annual camp, “a free holiday”, as one member put it, to deadly serious preparation for the real thing. All university OTCs had to double their numbers pronto as the early weeks of combat laid waste to not only the poor Bloody Infantry of the standing army but to the experienced, professional “officer class”.

Hence, this closing sombre note from The Gryphon in March, 1916: “The University has now lost the greater part of its men students. Many have left us, some sacrificing careers which can never be taken up again and the number increases of those who have made the greatest sacrifice of all.”

What have you done since leaving the University? Please remember to update your details with us.

The Liddle Collection

Items in the University's Special Collections Liddle Collection

Items in the University's Special Collections Liddle Collection

“All was mud and desolation, and there the depths of human misery, suicidal futility, and despair were surely plumbed,” wrote former Leeds Grammar School boy Captain Harry Oldham, 50 years on, recalling a day on the Western Front. “The casualties were frightful; indeed the dead seemed better off than the living. Oh what a lovely war.”

A group of students in the School of History uncovered his story while ferreting through the papers and other memorabilia from 4,000 people who lived through the first world war which comprise the University Library’s Liddle Collection. But the material they found wasn’t all muck and bullets by any means.

War having its daft and random aspects, the project came up with bizarre stories too. Captain Oldham himself actually got denounced as a spy when, on a York military hospital operating table after 1917’s third Battle of Ypres, he babbled in German. Not only that, he ended up marrying the nurse who’d accused him.

Then there’s the tale of Bertie Ratcliffe, nephew of the the Leeds Mayor Brotherton, who later endowed his book collection to the University. Taken prisoner in 1915, Bertie soon escaped and became the first POW to make it back to England, partly by dint of a compass which his mother had sent him concealed in a tin of Harrogate toffee. The compass now resides in the Liddle Collection.

The cable guy

In the shadow of the Fenton pub, recruits, both equine and human, trained to keep the Forces in touch with each other. Leeds lad Norman Woodcock joined the Royal Engineers Signals Corps at 17 and, like many of his generation, it wasn’t until after the war that Norman studied at the University.

First he had communications drills to follow, including “airline work – not flying but working up poles,” he’d later joke. Long hours training in signalling, horse care, riding, jumping and wagon driving prepared the recruits to transport and use precious communications cargo.

Norman said, “the wagons we used were, in fact, the signal offices with all the equipment on board to communicate along cables and lines.” He and his team would set off to train in the Yorkshire countryside, past the University’s OTC training ground, which was replaced by the old Mining/Fine Art building, now the Bragg Centre for Materials Research

Their six-horse-drawn wagons barrelled down winding country lanes while recruits fed communications lines off the back to Norman, who rode at speed close behind with his “crook-stick”.

The stick, when not entangled with galloping hooves and flailing stirrups, helped Norman lay the cables along the ground. A treacherous task in rural Yorkshire, let alone on the Front.

In the book 'On that day I left my boyhood behind’, Norman’s granddaughter, Susan Burnett (Mathematics 1983) brought together his memoires.

Written by Phil Sutcliffe, author of Nobody of Any Importance: A Foot Soldier’s Memoirs of World War 1

Photos from University of Leeds Special Collections

What have you done since leaving the University? Please remember to update your details with us.

Forever Leeds

350,000 alumni

One global community

Never miss a moment. Stay in touch and watch out for our emails.

Update your details