A new future

for children

of conflict

Changing the story

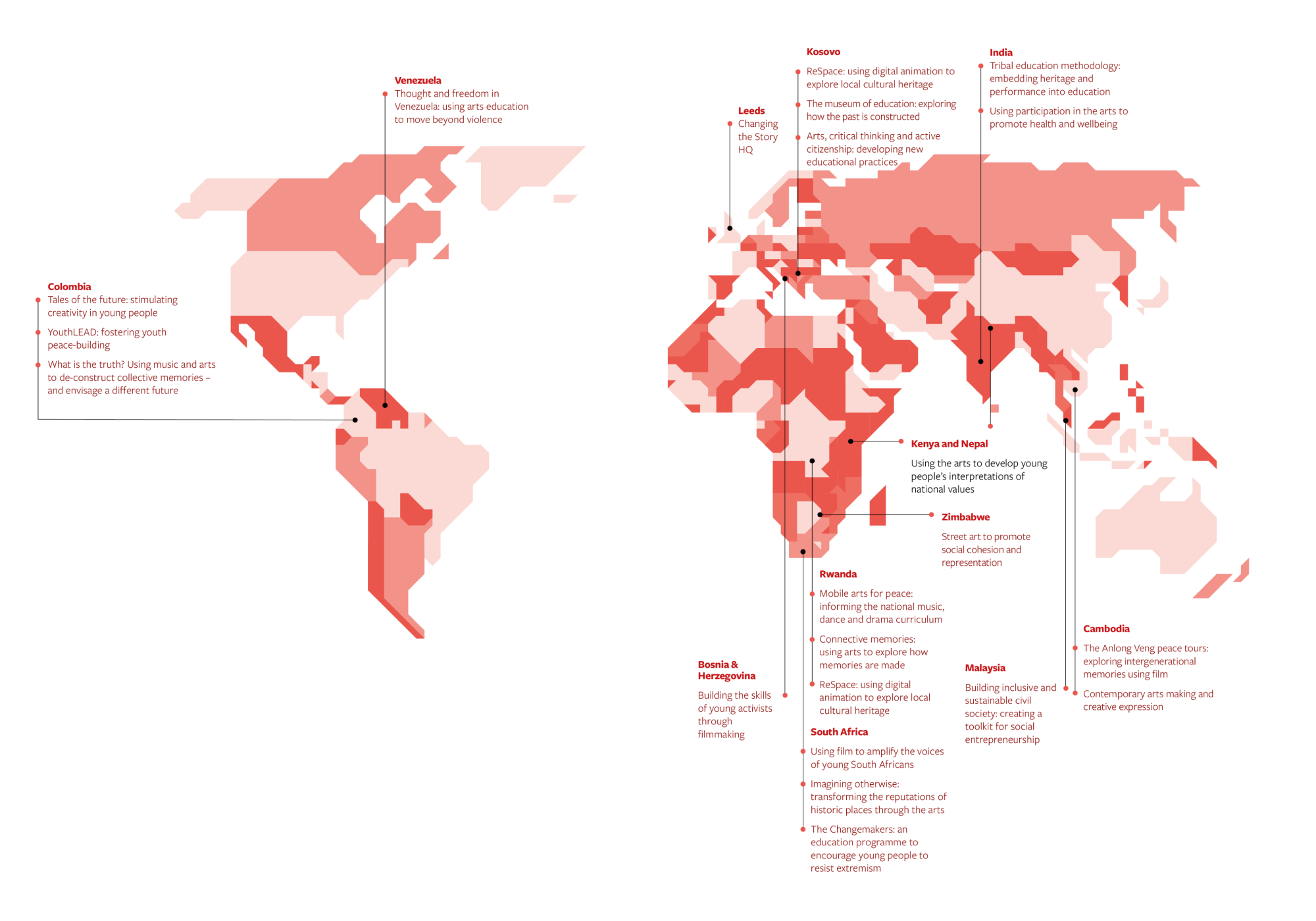

Across the globe, young people’s futures are overwhelmingly altered by the impact of conflict. 170 collaborations across 15 countries are helping to empower youth to change their futures using the arts.

A visit to South Africa proved a watershed moment for Professor Paul Cooke, Principal Investigator on the Changing the Story project. He travelled to Safepark, an out-of-school club supporting vulnerable young people, where they explored how to increase resilience through film.

“We used films about South Africa to get young people to reflect on the reality of their lives,” he says. “The young people we worked with generally felt that the films did reflect the realities of danger and violence, but they noticed that they tended to have sad endings.”

They didn’t see their lives that way, and when they created their own films, they wanted to change the story. “And so the name was born.”

Over the last four years, Changing the Story has created a platform to continue doing exactly that. By using art-based methods – film creation, animation, street art – hundreds of researchers and young people have developed youth-led interventions to support community resilience in post-conflict settings.

Changing the Story: 170 collaborations across 15 countries are helping to empower youth to change their futures using the arts

Changing the Story: 170 collaborations across 15 countries are helping to empower youth to change their futures using the arts

Although harnessing the power of the arts to engage young people is not a new concept, Changing the Story went further: “There hasn’t been enough research into the specific contribution young people can make to global development,” says Paul. “We wanted to make projects that were accountable to young people, not just designed by them.

“It is impossible to deliver on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals if we don’t take young people seriously,” he says. “Particularly in developing countries, they are ignored and they’re not engaged. So all our projects were youth-led, with our youth research board playing a key role in project management.”

In Zimbabwe, for example, researchers used street art to promote representation among marginalized rural Zimbabwean youth, providing opportunities to uncover and amplify hidden histories. In Kerala, India, tribal heritage, oral and performance traditions were used to develop a curriculum for indigenous tribes, decolonising learning for the group. In Malaysia, investigators studied how the arts can help develop entrepreneurial skills.

Exposition of artwork in Zimbabwe - Photo Credit: Faith Mkwananzi

Exposition of artwork in Zimbabwe - Photo Credit: Faith Mkwananzi

“It was the first large-scale comparative study of how civil society organisations work with young people in conflict affected societies. We started at grassroots, working with young people to then make regional and national policy impact. What began as five projects soon grew across the globe.

“The project officially finished in 2022, but the true legacy is now beginning to be seen.”

One of those key legacies was in Rwanda, where researcher Professor Ananda Breed, a project partner from the University of Lincoln, established Mobile Arts for Peace. “Many countries have an imperative to include creativity in their curriculum but have no mechanism for how,” she explains. “We built an informal grassroots network which then helped us to introduce the arts into schools and eventually the national curriculum.

“Once in place, we were then able to look at the value of different arts practices, and how to use art to deal with problematic pasts and historical trauma.”

The Mobile Arts for Peace project helped introduce the arts into schools and eventually the national curriculum

The Mobile Arts for Peace project helped introduce the arts into schools and eventually the national curriculum

As Paul notes, it was one of many projects which provided an impetus for further study: “The nature of it means you don’t know where you’re going to get to. Changing the Story findings and theories grew as a platform and people now incorporate our research findings into their own work.”

But Leeds alumni support was critical to the completion of the project. “Because of funding cuts to the Arts and Humanities Research Council during COVID-19, we were unsure how long we could continue. Alumni support gave us that reassurance and meant we could follow a long-term strategic plan.

“That funding has made a material difference to hundreds of young people’s lives in the places we’ve worked.” Paul recently travelled to Iraq, working with the UN to implement Changing the Story methodology to help overcome the challenge of being a minority in the country. Oxfam and the British Council have also been using Changing the Story’s research findings to inform youth-focussed strategy.

“Leeds facilitated a project which has had a huge impact globally, while supporting hundreds of people to develop their careers in practice and in academia,” says Paul.

“It’s changed everything.”

In Nepal, young people take part in a project examining interpretations of Civil National Values. Credit: Marlon Moncrieffe

In Nepal, young people take part in a project examining interpretations of Civil National Values. Credit: Marlon Moncrieffe

Truth-telling among former child soldiers in Colombia

In collaboration with El Rosario University, this Colombian-based project sought to facilitate the inclusion of former child soldiers in the country’s official narrative of the civil war.

“Former child soldiers are susceptible to PTSD and depression and can often find it difficult to establish social bonds and speak about their experiences,” says project lead Dr Mat Charles of El Rosario University.

“Ex-combatants can also display high levels of distrust in the state and its institutions. Our project aimed to build trust and foster the inclusion of these marginalised voices through creative methods, in particular animation.” Young people interviewed former child soldiers, before turning the interviews into theatre monologues, and later animations. “What they created was a series of powerful animations telling the experiences of the former child soldiers. The intergenerational dialogue was designed to help young people understand the history, but also contributes towards de-radicalisation in the next generation.”

An ensuing documentary was nominated for a number of awards including the Arts and Humanities Research Council research film prize, and the project led to longer term initiatives – such as development opportunities in journalism skills.