A passion play

When Lord Brotherton’s first foray into the world of rare books ended in failure, it proved the catalyst for a passion that consumed the remainder of his life – and gave our University a wealth of resources for teaching, scholarship and research.

“I think of it as the one that got away,” says Rhiannon Lawrence-Francis, Collections and Engagement Manager in Special Collections at Leeds.

In 1922, the City of Wakefield hoped to buy a medieval manuscript containing the Wakefield Mystery Plays – a cycle of religious dramas staged locally from the Middle Ages. It was being sold at auction and the city hoped to keep the manuscript local.

The city fathers approached Dorothy Una Ratcliffe, who in turn asked her husband’s uncle, the wealthy industrialist and former Wakefield MP Lord Edward Allen Brotherton, to step in. “He was very fond of his niece-in-law,” Rhiannon explains. “He had lost his own wife and daughter in childbirth and had grown very close to Dorothy.”

The pair travelled to Sotheby’s in London, and once the bidding passed the British Museum’s own limit of £1,400, Brotherton threw his own weight into the auction, until the price more than doubled. “He was an entrepreneur and he understood money. He would only go so far.”

The manuscript was bought by renowned American book dealer ASW Rosenbach – known as The Terror of the Auction Room – on behalf of Californian railway magnate Henry E Huntington. “At this time the building of libraries was bordering on obsession, particularly among American industrialists,” Rhiannon explains. Their interest in European culture spawned an exodus of cultural treasures.

To make up for Dorothy’s disappointment, Brotherton took her to the booksellers Quaritch, where they purchased a beautiful 1681 first edition of Miscellaneous Poems by Andrew Marvell. “That was their first rare book,” says Rhiannon. “But I wonder whether, had they been able to secure the mystery play manuscripts, that would have been it – and there would never have been a Brotherton Collection at all.”

Lord Brotherton decided to collect a library which would compare with The Rylands, the Bodleian and the Bibliotheque Nationale. He learned how these Libraries gave students and scholars opportunities for original research work; that they arranged exhibitions and gave public lectures.

“As it was, they quickly got the bug and began collecting in earnest. Brotherton decided to create a library representing the whole wealth and breadth of literature. Within a year he had appointed local bookseller John Alexander Symington as librarian at his Roundhay Hall home in Leeds, and together they bought rare books and manuscripts on an almost industrial scale. “It’s quite incredible,” says Rhiannon. “They would be sent catalogues from auctioneers and from libraries which were being dispersed – and simply buy the whole lot.”

Between the fateful auction in 1922 and Brotherton’s death in October 1930 they amassed 35,000 books, 400 manuscripts, 4,000 deeds, and 30,000 letters – that’s more than 20 items a day. “At the time when they were collecting, not long after the end of the First World War, many booksellers were on their uppers, and buyers got great value for their money.”

Among the collection were high-quality examples of incunabula – books printed during the earliest flourishing of typography in the 15th century – early modern and modern books, letters, charters and diaries. “I think they always had an eye on what was going to be useful in the future, but their first love was English Literature,” says Rhiannon.

“The Holy Grail of book collecting is a full set of 17th Century folios of Shakespeare’s plays. Within four years, Brotherton had acquired all four, including a 1623 First Folio, which he effectively repatriated by purchasing it from the estate of New York industrialist Theodore Vail. They are stunning.”

It was fashionable at the time to have books cleaned and re-bound; that Brotherton didn’t do this has given Leeds complete, unaltered copies of these rare documents – along with the notes, scribbles and annotations that make even printed items unique.

It is unclear when Brotherton decided to gift the collection to Leeds, though this last period of his life coincided with the University’s first significant fundraising campaign, one of the prime aims of which was to furnish the institution with a library befitting its growing status.

In 1927, he donated £100,000 to build this new library, which was modelled on the reading room of the British Museum – but slightly bigger. Though he didn’t live to see it completed, Brotherton spoke of his hopes when laying its foundation stone: “A great library in a great University is a trust for the nation at large and should not be looked upon as exclusively available for its own students.”

It’s a principle that holds true today: “Here we are 100 years later and it’s exactly what we do,” says Rhiannon. “The collection is here for everyone. People don't need any more reason to visit than just wanting to see these books and manuscripts for themselves.”

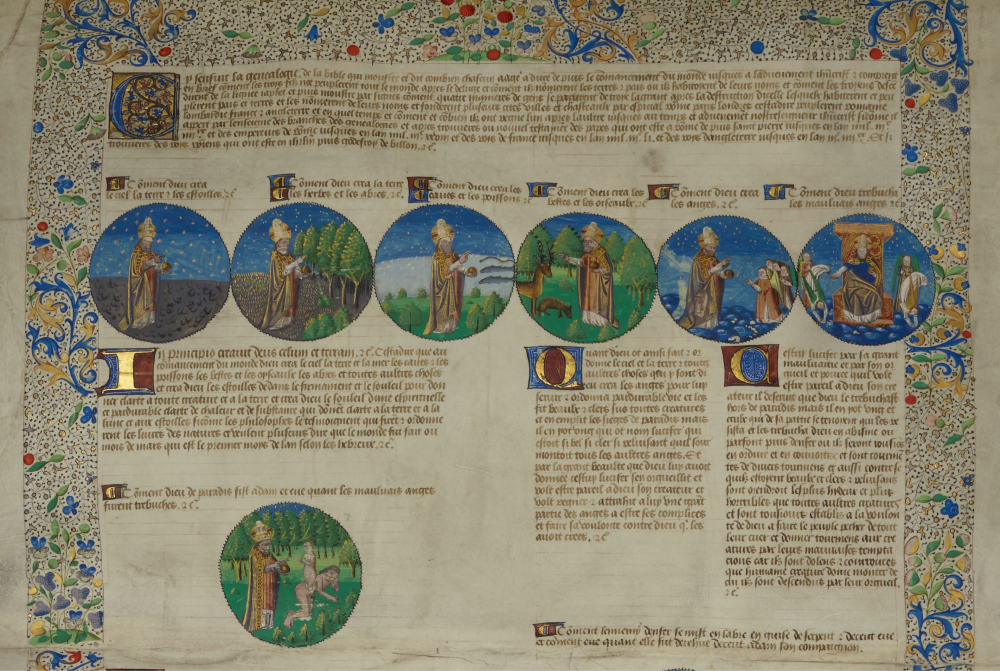

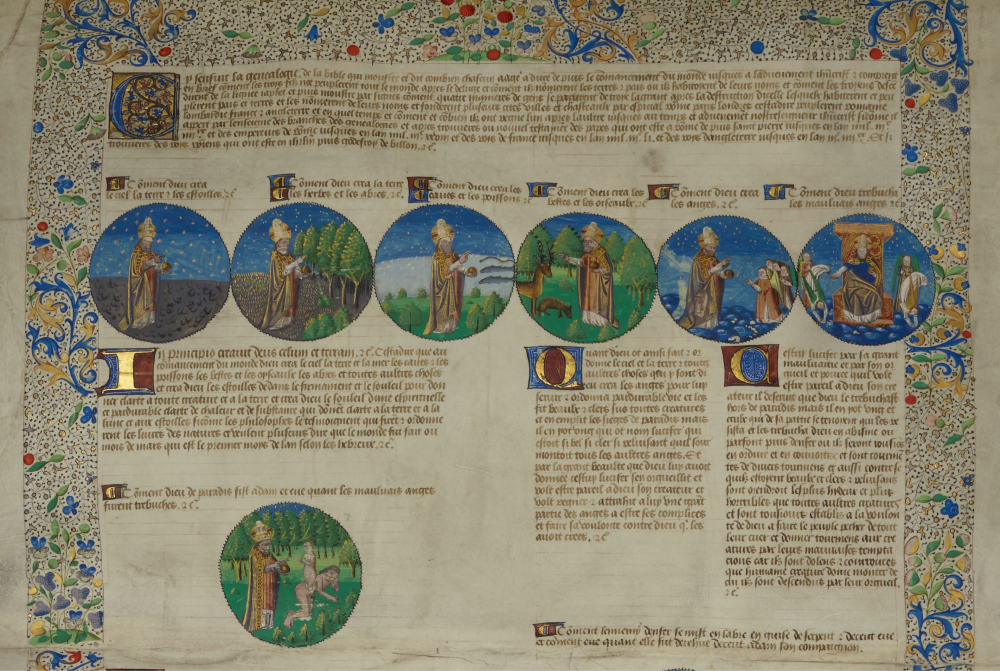

This illuminated French manuscript charts the history of the Christian world from the creation to the late 15th century in 18 metres of sheepskin. Written in Anglo-Norman French, it covers the Old Testament, the life of Christ, Greek and Roman history, and Western European history. In parallel columns it chronicles Popes, Roman Emperors, and French Kings alongside the history of Britain, the crusades and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. It is on permanent display in the Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery, though only a small section of the vast manuscript can be shown at any one time.

This illuminated French manuscript charts the history of the Christian world from the creation to the late 15th century in 18 metres of sheepskin. Written in Anglo-Norman French, it covers the Old Testament, the life of Christ, Greek and Roman history, and Western European history. In parallel columns it chronicles Popes, Roman Emperors, and French Kings alongside the history of Britain, the crusades and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. It is on permanent display in the Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery, though only a small section of the vast manuscript can be shown at any one time.

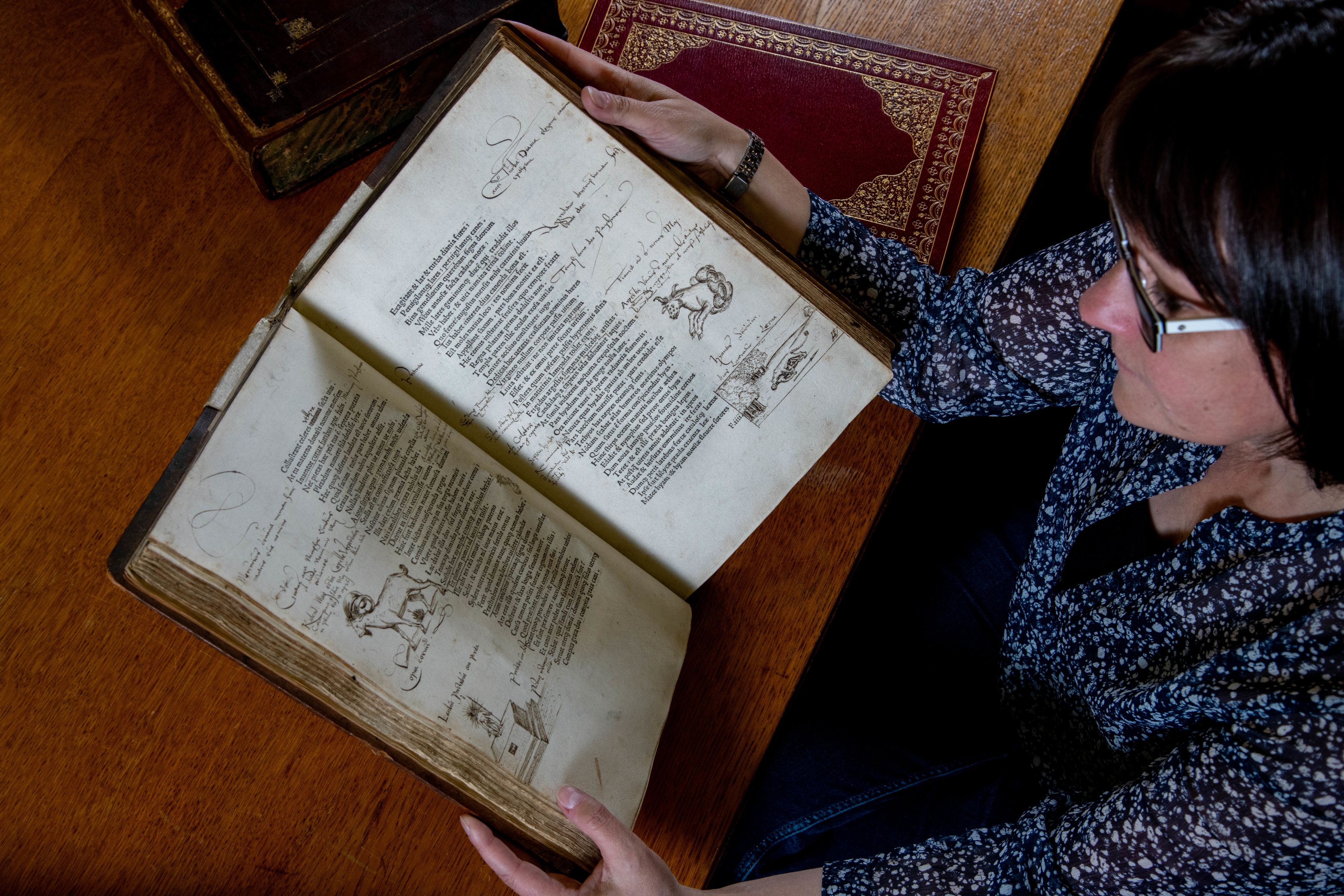

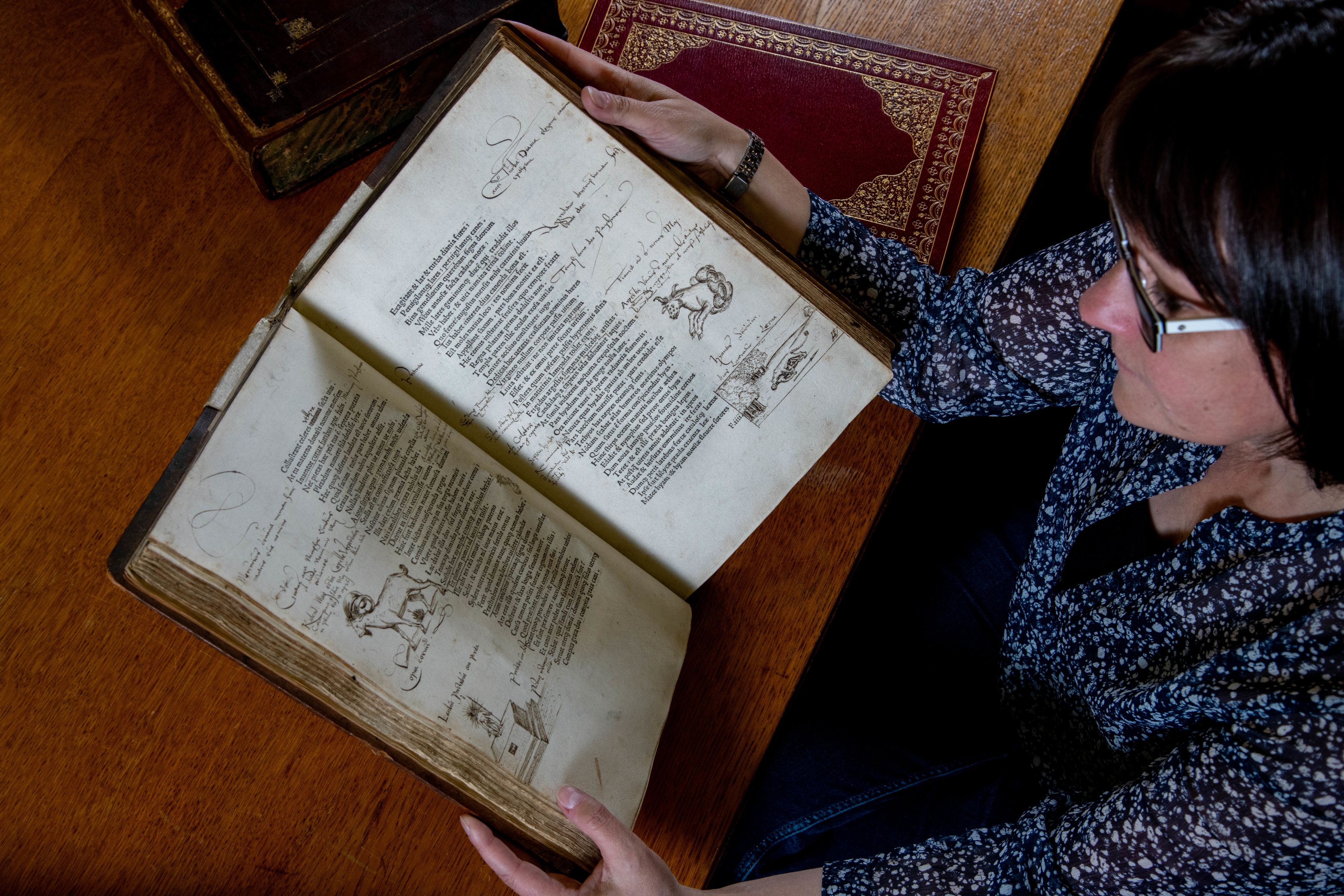

While working on a year-long project cataloguing our 15th-century books, Rhiannon became fascinated by this three-volume set of the works of the Roman poet Ovid, printed in Italy in 1477, which have numerous scribbles, doodles and notes alongside the text. Painstaking research unveiled the culprit: “We now know that most of the drawings and annotations were done by a young man called Oswald von Eck, when he was a student in Ingolstadt in the 1540s. I just had one year to catalogue the incunabula, but there’s a whole PhD in these three books alone!”

While working on a year-long project cataloguing our 15th-century books, Rhiannon became fascinated by this three-volume set of the works of the Roman poet Ovid, printed in Italy in 1477, which have numerous scribbles, doodles and notes alongside the text. Painstaking research unveiled the culprit: “We now know that most of the drawings and annotations were done by a young man called Oswald von Eck, when he was a student in Ingolstadt in the 1540s. I just had one year to catalogue the incunabula, but there’s a whole PhD in these three books alone!”

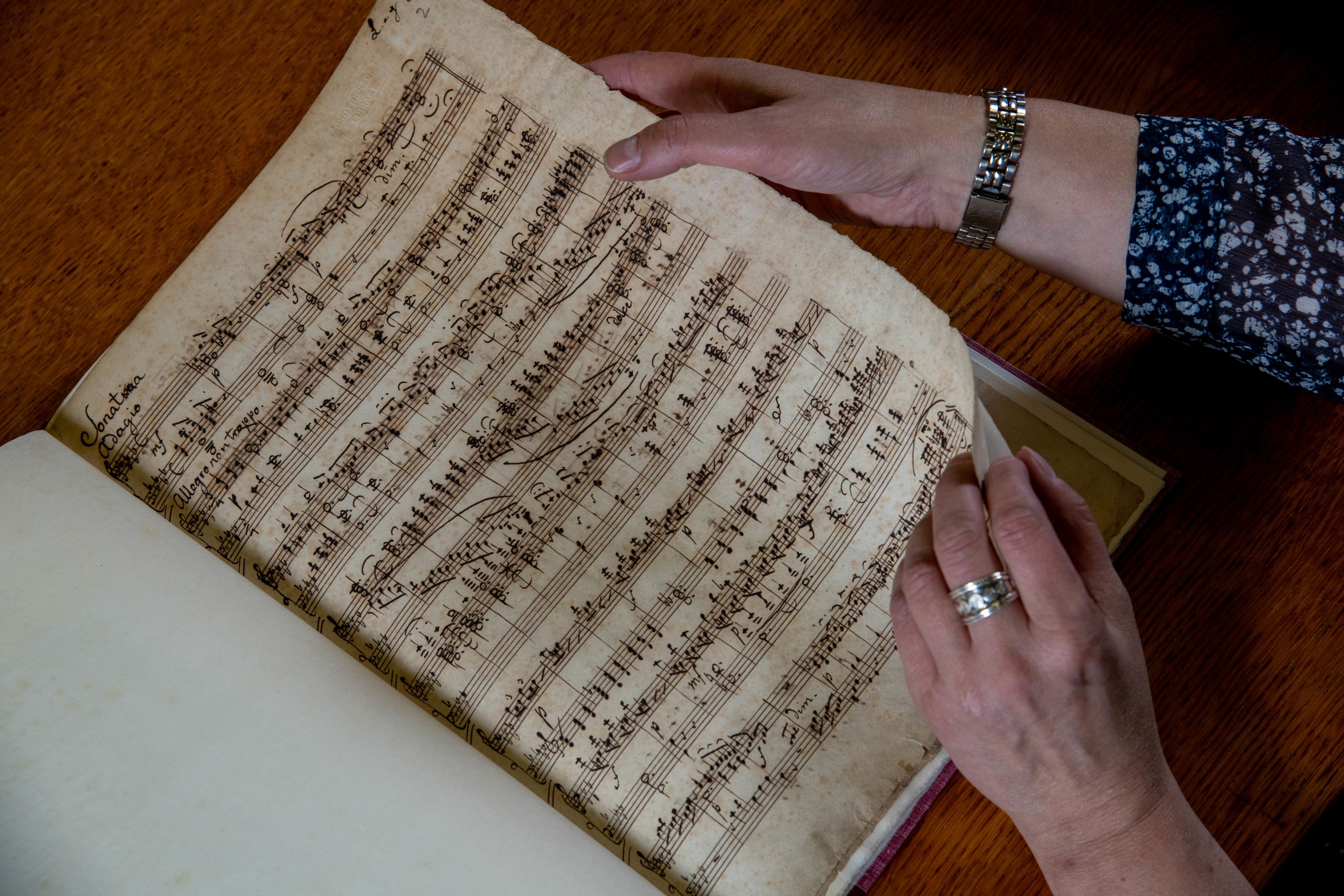

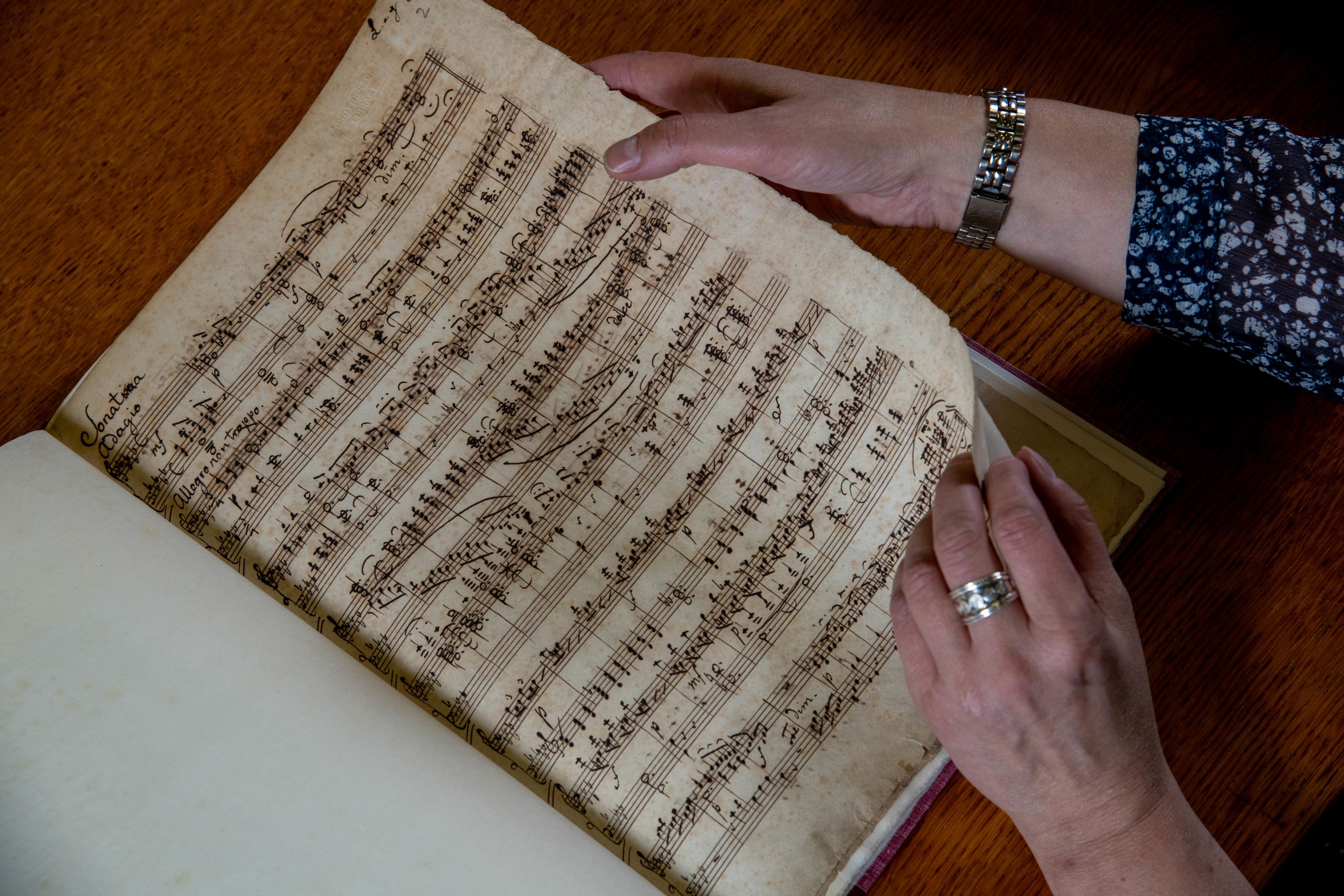

When Lord Brotherton acquired a collection of musical scores from Sheffield organist William Freemantle, he could scarcely have known it contained an unknown manuscript by romantic composer Felix Mendelssohn. The purchase included a number of Mendelssohn’s handwritten scores – which have long been a highlight of the Collection – but research showed that this 1823 Sonata in B flat minor had never before been published. The Leeds manuscript is the sole piece of evidence for this work; the teenage Mendelssohn even changed its original name from Sonatina, perhaps intending to expand it into a longer piece.

When Lord Brotherton acquired a collection of musical scores from Sheffield organist William Freemantle, he could scarcely have known it contained an unknown manuscript by romantic composer Felix Mendelssohn. The purchase included a number of Mendelssohn’s handwritten scores – which have long been a highlight of the Collection – but research showed that this 1823 Sonata in B flat minor had never before been published. The Leeds manuscript is the sole piece of evidence for this work; the teenage Mendelssohn even changed its original name from Sonatina, perhaps intending to expand it into a longer piece.

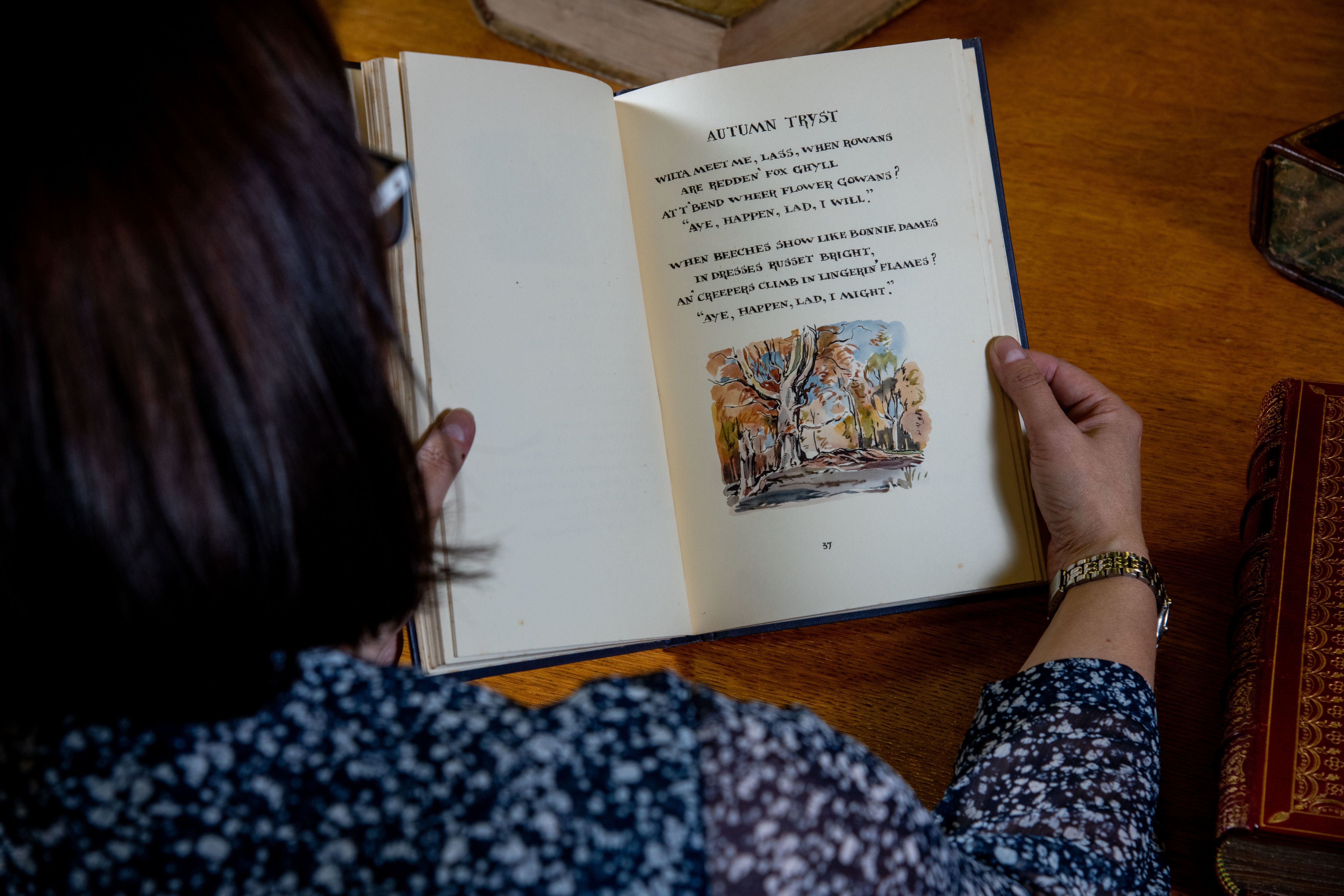

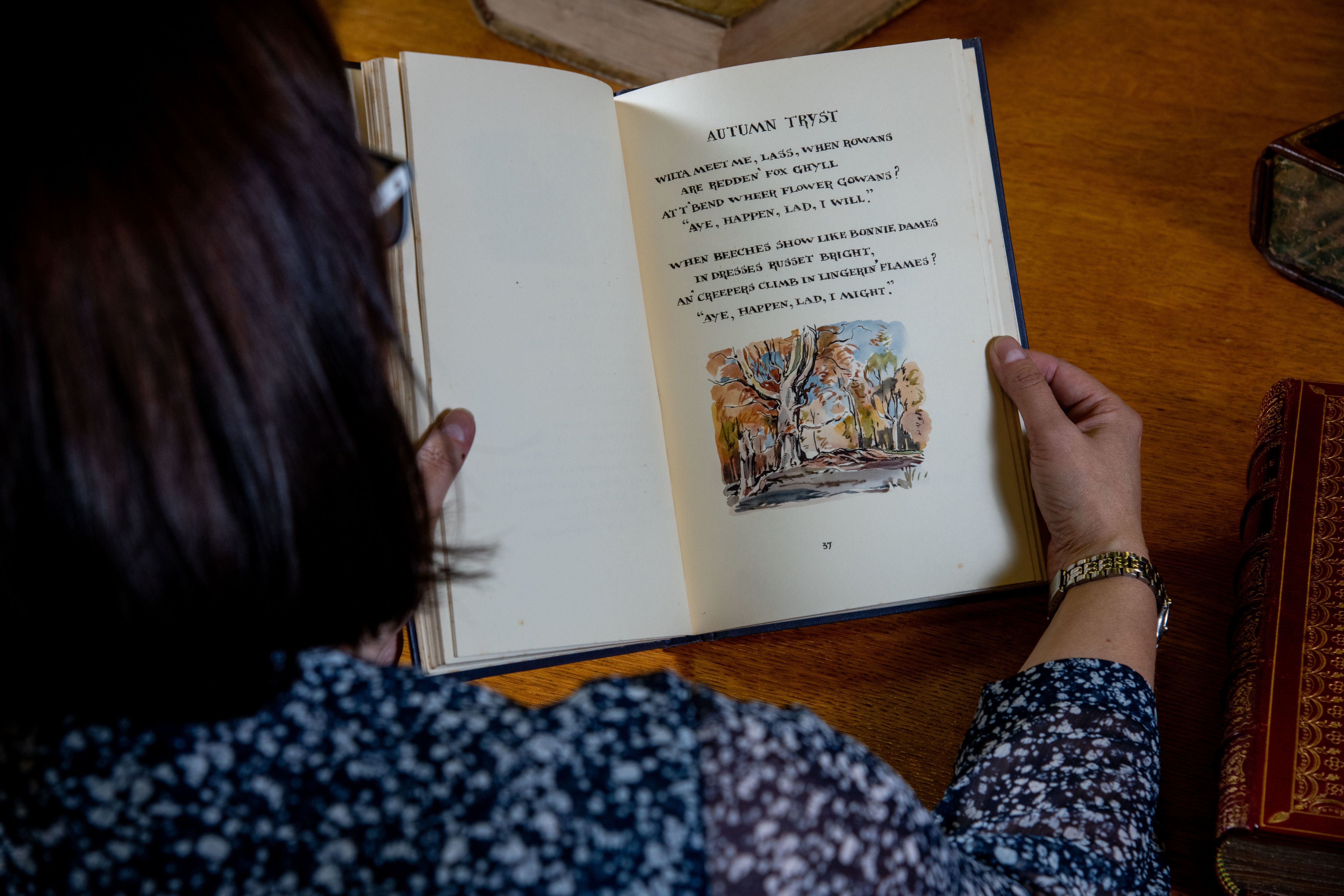

Dorothy Una Ratcliffe was herself a writer, and Dale Courtin’ is a unique collection of her own Yorkshire dialect poetry and was both handwritten and illustrated by her friend Fred Lawson. As well as working with Lord Brotherton to extend his own collection, Dorothy was a collector in her own right, compiling a library of books, documents and news cuttings about Romany life and culture, which she gave to the University of Leeds in 1950. The Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Collections are one of five Leeds collections that have been designated as “outstanding” by Arts Council England.

Dorothy Una Ratcliffe was herself a writer, and Dale Courtin’ is a unique collection of her own Yorkshire dialect poetry and was both handwritten and illustrated by her friend Fred Lawson. As well as working with Lord Brotherton to extend his own collection, Dorothy was a collector in her own right, compiling a library of books, documents and news cuttings about Romany life and culture, which she gave to the University of Leeds in 1950. The Gypsy, Traveller and Roma Collections are one of five Leeds collections that have been designated as “outstanding” by Arts Council England.

Your legacy, our future

Making a Will is one of the most important things you will ever do. By including a gift to the University in your Will, you will join a community of donors helping us nurture the people, generate the ideas and make the discoveries that will change the world for the better. Your gift could make a huge difference to the lives of our students or push forward research in an area close to your heart.

Dr Moses Batwala (Medicine 2000) is passionate about supporting the doctors of the future, and this has motivated him to pledge a generous legacy to the School of Medicine at Leeds.

I am delighted to make a gift to Leeds in my Will. Growing up in Uganda, I dreamed of becoming a doctor and studying here made that possible. I want to do all I can to encourage future medics to study at Leeds.”

Every legacy can make an impact, no matter the size. Find out how your legacy could make a difference or tell us about a gift you have already included in your Will.

On his death, Lord Brotherton bequeathed the contents of the Roundhay Hall library to the University, along with the endowment that enables its expansion to this day. There are now well over 100,000 items in the Brotherton Collection alone, and Rhiannon says his influence is still felt as it grows: “When looking at potential new purchases I sometimes find myself asking: ‘What would Lord Brotherton have done?’”

One of the most recent acquisitions is a 1647 volume of Comedies and Tragedies by Beaumont and Fletcher which once belonged to King Charles II. “It was published when the theatres were closed down by Parliament during the Civil War, so there was an added resonance purchasing it when our own theatres were shut during lockdown.”

Some treasures remain elusive: “I really wish we had a first edition of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. We have a second edition, but I’d like a first.

“There’s also a lot more we could do to make this amazing material discoverable, but this requires investment in skilled and knowledgeable people to explore the collection and share their findings. It would be wonderful if every catalogue record could show the complete history of an item, list all its previous owners and describe its unique features such as annotations, decorations, binding, and inserted material. But that’s very labour-intensive work, and we look after over a quarter of a million books across all of Special Collections.”

The one that got away

Passion Plays depicting Christ’s crucifixion, and other dramas depicting biblical scenes, emerged in the medieval period in cities such as York, Coventry and Chester. The Wakefield Cycle of 32 Mystery Plays was performed by the town’s tradesmen and guilds until at least 1576, when the Protestant church forbade any depiction of God, angels or demons.

The vellum manuscript that Lord Brotherton hoped to buy at auction is thought to date from the reign of Henry VII (1485 –1509) and covers the whole sweep of bible stories from the Creation to Judgment Day; its use of a 13-line stanza is a distinctive feature of several of the plays. It remains in The Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

The Brotherton Family remains closely involved with the University. The Charles Brotherton Trust supports the library through annual donations and in 2018 established The Brotherton Poetry Prize to promote new and unpublished poets.

In 2016, the family contributed to the establishment of the Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery, which has enabled the library team to focus on engaging the general public with the collection through both a permanent display of highlights and changing exhibitions. The current exhibition, which runs until late 2022, features the story of the Cottingley Fairies – the famous photographic hoax perpetrated by two schoolgirls.

An engagement space allows visitors to get up close and personal with these treasures. “Lord Brotherton wanted his collection to be used, researched, discussed, handled, and most of all enjoyed – and that’s exactly what we make happen. People love the fact they can come and see handwritten items by the Brontë sisters, a lock of Mozart’s hair, a letter from Tolkien to Arthur Ransome bemoaning the poor sales of The Hobbit.”

Moving engagement events online during the pandemic opened the collection to a much wider audience – and early in 2022 an online exhibition will celebrate 100 years of the Brotherton collection. “Apparently one of our talks was advertised in New York Public Library. We got hundreds of people from all over the world joining us via Zoom.”

Even so, Rhiannon is delighted to be back on campus: “It’s so exciting to work with these precious materials. It makes you want to get up in the morning. The whole team in Special Collections are enthusiasts and during lockdown we really missed being on campus. It’s great to be back among all these wonderful things.”

Watch, as Head of Special Collections Joanne Fitton talks about how our amazing resources have been amassed over more than a century – and continue to inspire.

What did you think?