Leeds at the WHO: Ian Smith

Leeds graduate Ian Smith is Senior Advisor to the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) and Head of the Secretariat for the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board.

Dr Ian Smith, Senior Advisor to the Director-General of the WHO and Head of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board

Dr Ian Smith, Senior Advisor to the Director-General of the WHO and Head of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board

Dr Ian Smith graduated with a Medicine degree in 1980 and returned to Leeds to complete a Masters in Public Health in 1994. From the very core of leadership at the World Health Organization, Ian gives us his remarkable and frank insight on working in public health.

As an advisor to the highest leaders at the WHO, what sort of things do you do?

I get to see the entire work of the organization at all levels, right down to the community level in member states.

Our global work is largely around the normative aspects of global health — setting standards and policies and providing technical advice. We're also increasingly involved with operational support to countries with the development of their health systems and work in health emergencies.

I try to provide helpful feedback or ideas and advice to the Director-General and to other senior staff. I try to encourage the organization to work effectively and to be true to the WHO’s values and principles.

The World Health Organization celebrates its 75th anniversary.

The World Health Organization celebrates its 75th anniversary.

What are the WHO’s values and principles?

The WHO’s constitution has quite wonderful language about the extraordinary purpose of this organization to deliver health for all people.

Our 75th anniversary motto 'health for all' means protecting people from health emergencies, promoting health and providing health through strong health systems based on universal health coverage and primary health care.

The preamble to the constitution says “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” That’s a very profound statement that was written back in the 1940s.

It was already then clear that you can’t just consider health as the opposite of disease. It's more about well-being that encompasses our whole being.

Health is really fundamental to achieving world peace and security. That’s still as true today as it was when the constitution was written 75 years ago.

The constitution also says “health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent on the fullest cooperation of individuals and states”.

This was written shortly after the Second World War, and it was making the point that health is really fundamental to achieving world peace and security. That’s still as true today as it was when the constitution was written 75 years ago.

How did a Leeds medical student end up advising the Director-General of the WHO?

It's an immense privilege to do my work at the WHO. I have a dual role as Senior Advisor to the WHO’s Director-General and I’m also head of the Secretariat of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board.

My first jobs after graduating were in local hospitals — Dewsbury General, Pinderfields in Wakefield, casualty at Leeds General Infirmary and paediatrics at Jimmy’s.

Then in early 1984 my wife and I went to Nepal. We started out in a small village hospital up in the mountains that was a six hour bus journey from Kathmandu, followed by a six hour walk up into the mountains.

I got more and more involved in Tuberculosis (TB) control and we moved to the district capital to work with the District Health Office. We came home to do my Masters at the Nuffield Centre and then we returned to Nepal in 1994 and I continued working on TB. We eventually moved to Geneva to work at the WHO headquarters.

Ian advises the WHO's Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. © WHO

Ian advises the WHO's Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. © WHO

I helped set up the Global Drug Facility for TB drugs. It was a fantastic initiative designed to provide high quality, low cost, TB drugs. It has made a massive contribution to TB control globally, particularly in developing countries.

And then the head of the TB programme, Dr Jong-wook Lee, was elected as the Director-General of WHO, and he invited me to move with him as an advisor when he took office in 2003.

Have you been advising the Director-General since then?

I worked with other director-generals since then and became Chief of Staff around 2014. I left in 2017 and then the current Director-General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, invited me back to the WHO in late 2019, just before Covid-19 hit.

I was working initially as a consultant and then went back on staff again, largely because of Covid-19. I was in Geneva for that first year of lockdown and my family was back home in Yorkshire.

Meanwhile, you're also involved with a board set up by the WHO and the World Bank?

I also head up the the secretariat for the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB), which is an independent body established by the WHO and the World Bank.

It monitors the state of the world's preparedness for health emergencies, and advocates for action to address the weaknesses that are obvious in health emergencies.

That report came out just weeks before Covid-19 broke out. The GPMB was simply stating the obvious — the world was not prepared for a pandemic.

Was it this board that predicted the pandemic?

The Board's first report, before I got involved, came out in September 2019. The report predicted that there would be a major global pandemic that would cause immense numbers of deaths and immense economic damage.

That report came out just weeks before Covid-19 broke out. The GPMB was simply stating the obvious — the world was not prepared for a pandemic. Covid-19 demonstrated what should have been obvious to all.

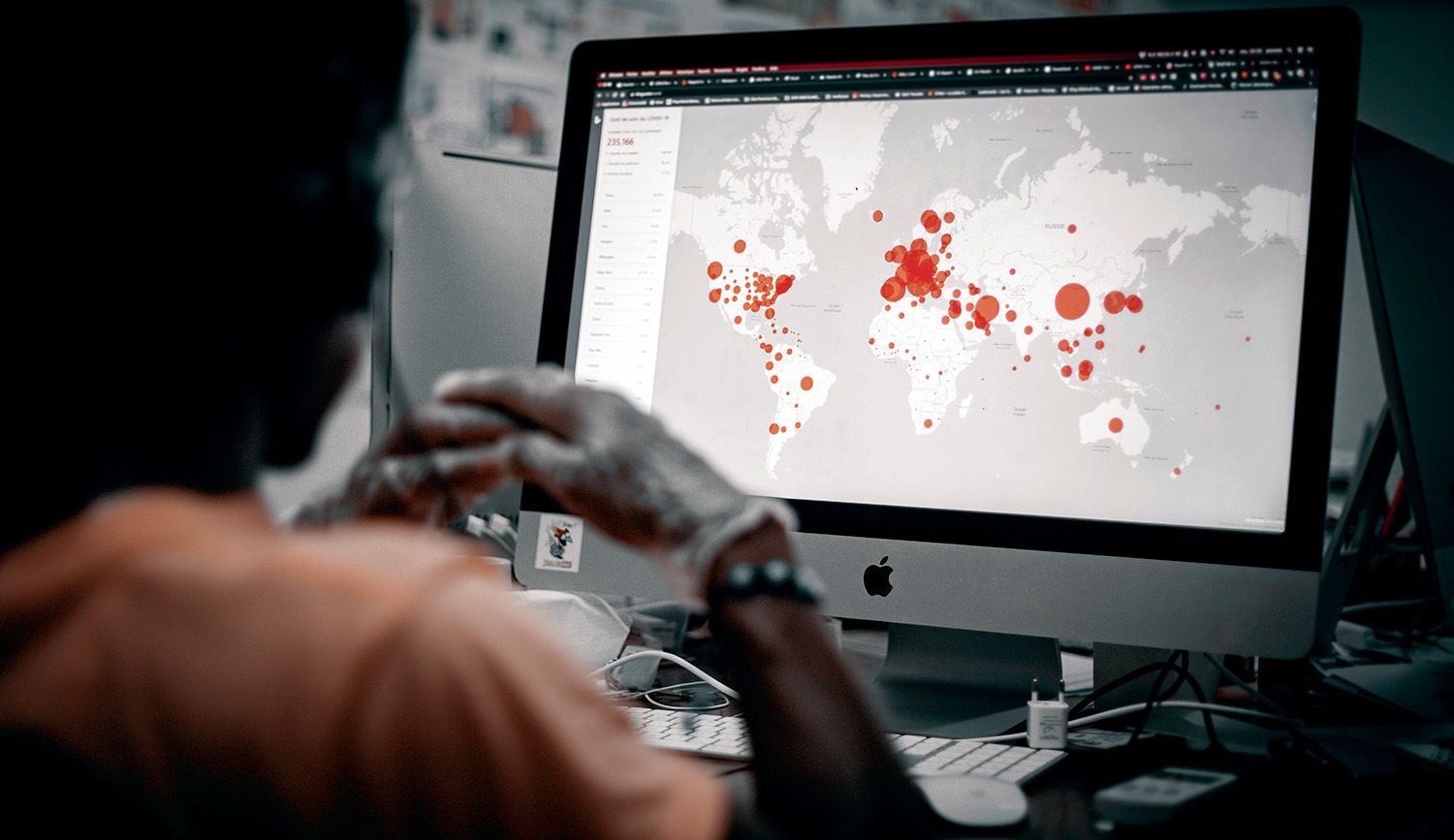

The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board monitors the state of the world's preparedness for health emergencies.

The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board monitors the state of the world's preparedness for health emergencies.

We saw extraordinary responses from different countries with some demonstrating real leadership and commitment to evidence, science and a public health response.

Others chose a much more political response, asking themselves how they could strengthen their political power through this. And they ended up taking all sorts of actions which were entirely inappropriate and extremely damaging, both nationally but also, importantly, internationally.

The key point about pandemics is that these are existential threats to the world. No one country can deal with a pandemic on its own. It demands collective effort.

The key point about pandemics is that these are existential threats to the world.

When Covid-19 hit, we quickly focused our attention on identifying what the key problems were, where they were emerging and then highlighting what was needed in order to address them.

So often, people immediately ask for money for better systems and new technologies. Although systems and technologies play a critical role, we can’t ignore the human dimension of pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

Leadership is critically needed to ensure that capacities are used effectively, but also that information provided to people and communities can be trusted and is contextual to where people are.

Leeds alum Mary Stephen, Public Health Expert and Technical Officer, Africa Region, ensuring that the message is contextual to Tanzanian listeners

Leeds alum Mary Stephen, Public Health Expert and Technical Officer, Africa Region, ensuring that the message is contextual to Tanzanian listeners

Everybody puts in energy and resources when there's a major crisis but when the crisis passes, everything returns to the normal state of affairs, which is to ignore it.

The GMPB is fearful that, although Covid-19 is still around, the attention on pandemic prevention and preparedness is rapidly decreasing as other crises arise.

We made a very clear point at that time that it's essential that we have good governance to bring together leaders, communities, systems and finance.

How do we prepare for the next pandemic?

The WHO’s working on negotiating a new treaty for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

There's work around amendments to the International Health Regulations, which are the regulatory framework particularly for surveillance and early response and sharing of information.

A WHO discussion "Towards a new architecture for health emergency preparedness, response and resilience: 10 proposals for a safer world" in May 2022. © WHO / Laurent Cipriani

A WHO discussion "Towards a new architecture for health emergency preparedness, response and resilience: 10 proposals for a safer world" in May 2022. © WHO / Laurent Cipriani

There's a high level meeting on pandemic prevention preparedness and response at the head of state and head of government level being held in New York in the General Assembly in September this year.

There's work around a new pandemic fund at the World Bank to make sure that there are investments flowing into preparedness in countries.

A new countermeasures platform is being developed for vaccines, drugs and diagnostics and other health medical equipment. There are technologies being developed to get equitable access to these countermeasures.

There's a lot of work ongoing around surveillance, as well, to make sure information is shared effectively, rapidly and appropriately.

Some in the pharmaceutical industry caused 'a horrendous story of everything going wrong' for people in most need of pandemic countermeasures

Some in the pharmaceutical industry caused 'a horrendous story of everything going wrong' for people in most need of pandemic countermeasures

How can we avoid repeating our mistakes?

Information that's provided to people and communities needs to be trusted and presented in a way that doesn't appear to be blaming people. It needs to support and engage with communities contextually, where they are.

We saw WHO’s principles of equity get pushed to one side during the pandemic. The way that Covid-19 vaccines were developed was quite extraordinary and a wonderful success story. The gross inequities in access, as the richer countries just bought up supplies, tells exactly the opposite story.

Many in the pharmaceutical sector have made billions out of the sale of these vaccines. It’s a horrendous story of everything going wrong when it comes to ensuring that the people in most need get the countermeasures they need.

The GPMB proposes three tests to make sure that things are going in the right direction.

Number one, we need to test if each reform is strong enough to deliver what's needed. If the reform isn’t effective, it occupies the space of another initiative that could work better.

The second test is about coherence. Do reforms from many disparate areas — and we need to reform many areas — actually work together? If we reform them all separately, they won’t be interoperable. So, for example, we must ensure that a pandemic fund is linked to national action plans for preparedness and response.

The Board’s third test is whether monitoring and accountabilities are built into the reforms. This is the only way we’ll know if reforms actually are as effective as we need them to be.

We need to ensure people have access to the information that they need – and try to identify when false information is being put around.

Everybody's aware that a pandemic of this size, and any major health emergency, goes way beyond the health sector. It involves many other sectors — education, environment, animal health, finance and economics, trade and travel. So, we work with health experts but we also have economics experts and animal health experts.

We have leadership experience in socioeconomic development and gender, human rights and R&D. We draw on the expertise from UNICEF, World Organization for Animal Health, World Bank and IMF, and others to make sure we're pulling in good expertise, evidence and data.

This is not just an approach at a global level.

Everything begins at the community level, particularly in health emergencies. It's more about informing the public and engaging with them.

We need to ensure people have access to the information that they need – and try to identify when false information is being put around.

What do you consider to be the WHO’s greatest successes?

The WHO’s had enormous impact since it started. The whole work around primary healthcare, the Alma-Ata Declaration in the 1970s, really was a watershed moment for public health.

The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has contributed to a profound decline in the use of tobacco in many countries

The eradication of Smallpox is an obvious major success for the WHO. There’s also a close-to eradication of Polio, the extraordinary decline in many infectious diseases and the adoption of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which has contributed to a profound decline in the use of tobacco in many countries. There’s a long list.

But it’s not so much the big wins, but rather the constant support and enabling that the WHO does at the country level. The WHO’s work at the country level is really what we should be highlighting.

Is it actually possible for world governments to collaborate on health?

We've seen in recent years a general decline in the confidence of multilateralism as a means to deliver on improvements in our well-being.

And yet, what's being proposed as an alternative?

If we've learned anything, it’s that we need to develop ways for countries and communities to work together so they don’t pursue an individual nationalistic approach. The WHO is more important than ever before to enable this approach.

Ian's link to Leeds

Do you still have any links to Leeds?

I've remained engaged with the University of Leeds. There’s a group of Leeds students that visits our headquarters every year. I've usually been involved in meeting with them and giving them a quick briefing on the work of WHO. I love to speak to them and it's always inspiring just to see the diversity of that group.

I only recently realized I was working with Leeds alumni here in Geneva. Stella Chungong studied at Leeds and, only last week, I discovered that Jim Campbell is a Leeds alum too.

Forever Leeds

312,000 alumni

197 countries

One global community

Never miss a moment

Update your details

Follow @LeedsAlumni